Hear me, great saviours, and from the most sacred books grant me holy illumination, scattering the mist, so that I may clearly recognize immortal gods and men.

— Proclus Hymn IV. 5-8

Preamble

What has Athens to do with Jerusalem, or, to adapt Tertullian’s famous question, what have the poems of Homer to do with the Qur’an? For the absolute majority of their partisan believers (whether they be Muslim or Christian), the answer is ‘nothing at all’. For many contemporary scholars the possibility of such a comparison is like a postmodern fiction, comparable to the countless others in the masquerade of silly ‘dialogues’ and triumphant ‘comparisons’ that occur. However, the theme is worthy of exploration, setting aside, of course, the dangerous aspects of the topic, whereby seeming challenges to fundamental religious premises could provoke inevitable antagonisms among those who imagine themselves as the guardians of truth against ‘pagan’ fallacy.

Both in the ancient Near East and Hellas, hermeneutical methods and strategies are closely tied to or rather directly depend on the imagined cosmological structure of being and its mythical horizon, understood as a symbol of the divine. Therefore hermeneutike – the ‘art’ (if not a ‘science’) of explaining sacred omens and tokens or of interpreting signs of cosmic texts and spiritual traditions – can be a means of translating one order of existence into another thus giving an articulated meaning to the Reality and making it accessible to the human mind at its own limited level. But hermeneutike also can acquire an elevating function and power which transcends the discursive level of human thought and can lead the soul (transformed by illuminative spiritual exegesis) to the immortal gods. In a sense, hermeneutical procedures consist in the following:

1) naming or re-naming things and thus creating classifications or semiotic sets of ontological and mythological entities;

2) both revealing and concealing realities or simulacra – the phantoms of imagination;

3) pointing to ineffable mystery and confirming the established world-order;

4) guiding one to the right end or providing the right response;

5) radiating intelligible light which disperses the Typhonian darkness, and

6) elevating the soul to the heights of spiritual contemplation.

These hermeneutical procedures and operations are inseparable from and, in certain important cases, tantamount to the sacred rites that operate on the integral basis of mythic cosmogony and by extension are projected into the realm of noble politics, social relations, daily sacrifices, magical practices and a priori outlined tasks of philosophical anamnesis.

Hermeneutics

John Dillon, in his article Pleroma and Noetic Cosmos: A Comparative Study, argues that the idea of a whole articulated archetypal world by reference to which, as patterns, our physical world is made by God, forms no part of traditional Jewish or early Christian thought.[[1]] Instead the Timaeus of Plato speaks of the Essential Living Being which contains within itself the archetypes of the four elements and Ideas of all the living creatures (Tim.30b and 39c). This autozoon is regarded as an eidetic fullness or pleroma. It provides both the initial starting point and the final point of reference to any particular instance in the world of becoming.

Within the beautiful hierarchy of the arranged theophanies, the higher cares for the lower, and cosmic Eros … serves as a hermeneus for the contemplative ascent to the divine source, symbolized by the Sun

Accordingly, any movement of metaphysical or theological interpretation and allegorical reading must be thought of, in its ultimate and ideal sense, as an epistrophic vector leading towards an archetypal meaning and the original source of manifestation. Hermeneutics (understood as an inspired exegesis and scholarly interpretation conducted according to the set of canonized rules) becomes a sort of anagogic rite which is analogous to the ascending path of Platonic dialectics and theurgic elevation. And the fullness of the noetic cosmos, which may be linked to ‘a globe of faces radiant with faces all living’ (Plot.Enn.VI.7.15), through the mediating power of logos, and its divine irradiations (elampseis), can be mirrored on the microcosmic level of hieratic images and texts.

The intelligible totality (to alethinon pan) of Forms, or noetic entities, contains in itself a pattern of all phenomena. According to Neoplatonic exegesis, all these noetic entities, arranged in a hierarchy of intellects and Forms of greater and lesser generality, are interpreted as the gods of traditional theology and mythology. In their primordial essence, the gods transcend even the noetic order and are tantamount to the web of ineffable henads, or unities, which is regarded as the metaphysical basis for all theophanies and the supra-ontological foundation of all levels of reality. Within the beautiful hierarchy of the arranged theophanies, the higher cares for the lower, and cosmic Eros manifests itself not only in Providence but also serves as a hermeneus for the contemplative ascent to the divine source, symbolized by the Sun in the famous simile from Plato’s Republic (507a-509c).

The image of the divine Sun as well as that of the archetypal Living Being, autozoon (viewed as a triad of Being, Life, and Intelligence by the later Platonic tradition), is hardly invented by Plato himself and can be traced back to the ancient solar theologies. Only the means of expression and communication may differ, though the rational philosophical discourse of the post-Aristotelian Greeks looks simply to be a clearly observable summit of the huge misty mountain.

Our present task is not to search for mysterious origins of the ancient metaphysical thought and sacred hermeneutics (be it regarded as an explanation of dreams, oracles, and omens, or a clarification of the luminous divine presence during the temple rites), but rather to explore some analogies between interpretation of the Homeric poems in the ancient Hellenic philosophical paideia and that of the Glorious Qur’an in the much later Islamic tradition. The comparison is made in two respects:

1) as regards metaphysics of the divine Ideas (Names) and their manifestation (the aspect of cosmogony and revelation),

2) as regards an anagogical ascent through the contemplation, purification, sacred rites and interpretation of the privileged text (the aspect of virtue, theurgy, and aesthetics.)

Hierarchy of Interpreters and Interpretations

When the language of the Qur’an is regarded as the crystalization of the Divine Word in human language, scattered by the ‘weight’ of the revelation from on high[[2]], the Neoplatonic tripartite scheme of remaining, proceeding, and reversion immediately comes to mind. What proceeds is altered by different conditions of multiplicity, but, despite this contingent alteration, the famous Delphic maxim ‘Know thyself’ (attributed to Apollo) remains a key to the entire hierarchy of being and knowledge which is surmounted by the divine unity. The levels of being are also levels of knowledge, therefore the nature of knower determines the mode (tropos) of the object known or perceived. This is why Proclus, the eminent Hellenic philosopher and theurgist (c.A.D.410/412-485), argues:

‘Instead the mode of cognition (gnoseos ho tropos) becomes different according to the differences of the knowers. For the same thing a god apprehends unifically (henomenos), intellect wholly, reason universally, imagination figuratively, sensation sensitively. Because the object of knowledge is one, it does not follow that the knowledge of it is also single’ (In Tim.I.11.16-19).

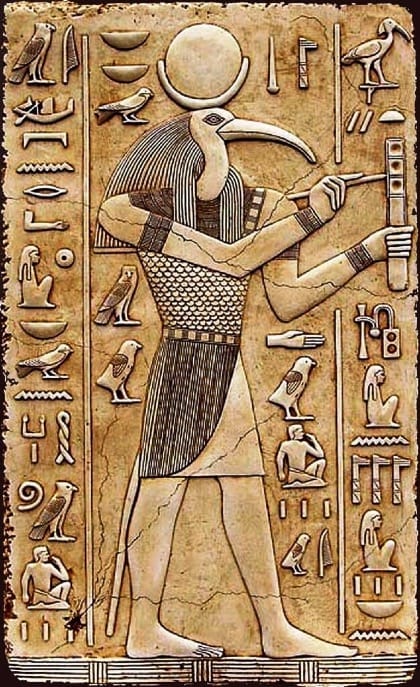

This approach recognizes the different levels of being and knowledge, as well as the dynamic hierarchy of interpreters and interpretations. Hence, there are numerous levels of language and meaning descending from creative divine language (divine words, medu neter, or the speech of Thoth, who is regarded as the intellect and tongue of Ra by the ancient Egyptians) down to the language found on the fragmented and dispersed level of the physical existence and sense perception. According to Proclus:

‘The transcendent Forms exist by themselves (kath’ auta). Those that exist by themselves and of themselves are not in us. What are not in us are not coordinate with our knowledge (epistemen). What are not coordinate with our level of knowledge are unknowable (agnosta) to our knowledge. Therefore the transcendent Forms are unknowable to our knowledge; they are contemplated (theata esti) only by the divine Intellect. This is so for all the Forms, but especially for those that are beyond the intellective gods. For neither sense-perception, nor knowledge based on opinion, nor pure reason (logos), nor our own intellective knowledge connects the soul (psuche) to those Forms, but only an illumination (ellampsis) from the intellective gods renders us capable of being connected to those intelligible-and-intellective (i.e. noetic-and-noeric) Forms ... And for this reason, indeed, Socrates in the Phaedrus (249d)... compares their contemplation (theorian) to mystery-rites (teletais), initiations (muesesi) and visions (epopteias), elevating our souls under the arch of Heaven, and to Heaven itself, and to the place above Heaven‘ (In Parm.949.13-38).

the ‘unitary’ divine language suffers fragmentation, is divided and deformed in the process of descent. The task of hermeneus is an angelic task of revelation, adaptation and elevation back to the source which is beyond the reach of hermeneutics.

In the Procline hierarchy of ontological orders (taxeis), each logos has a coherence according to that particular level of being to which it belongs. The contradictions and inadequacies of the logos on each lower level can be resolved by reference to certain meta-language or a more coherent archetype found on the immediately higher level from which the lower one ‘proceeds’ in metaphysical and logical sense. Thus each lower language or discourse (that may be regarded as an image, eikon) functions as the interpreter (hermeneus) of the higher one. It translates the higher truth to the lower level of perception and understanding at the expense of its coherence, because the ‘unitary’ divine language suffers fragmentation, is divided and deformed in the process of descent. The task of hermeneus is an angelic task of revelation, adaptation and elevation back to the source which is beyond the reach of hermeneutics.

Descent and Ascent

Descent and Ascent in philosophy covers important theological themes of manifestation and return to the Principle, of demiourgia and theourgia. These are closely related to the ancient cosmogonies and cosmologies, especially of Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Anatolia. The Neoplatonic ideal of the epistrophe, return to the native Star, represents the end of philosopher’s journey. It repeats the ideal of ritualized sacrifice, reproduced by analogy in all compartments of life, including the social (and therefore cosmic) realm.

every Sufi follows the Prophet as an archetypal guide to the noetic realm of Light. And the Prophet’s essence and nature is that of the Qur’an

The Islamic religious metaphysics is also based on such universalized mythological and soteriological scheme. It has a Night of Power (laylat al-qadr), when the Qur’an descends, and a Night of Ascension (laylat al-mi’raj), when the Prophet ascends to the divine Throne. Consequently, every Sufi follows the Prophet as an archetypal guide to the noetic realm of Light. And the Prophet’s essence and nature is that of the Qur’an (kana khula-quhu al-Qur’an). He is the ever-living model of Islamic spiritual life.

The ancient Egyptian pharaon (per aa, a big house, meaning a sort of temple), is the living Horus, the son of Osiris-Ra, who is immortalized as a hypostasis of pantheos and regarded both as a Philosopher (mer rekh) and a Priest par exellence. He serves as a prototype of the Gnostic anthropos and the Perfect Man (al-insan al-kamil) of the Sufis. This symbolism is referenced in the Pyramid Texts:

‘Stairs to the Sky are laid for him that he may ascend thereon to the Sky’ (Pyr.365)

‘King Unas ascends upon the ladder which his father Ra made for him’ (Pyr.390)

‘O Pure One, assume thy throne in the barque of Ra and sail thou the Sky... Sail thou with the Imperishable Stars, sail thou with the Unwearied Stars’ (Pyr.1170-1171).

One can understand how these ideas and images correspond with the much later Islamic terms: a pharaon can be understood, according to certain cosmological and theological perspective, to be both the Book and the Prophet. He is the Book in the sense of an archetypal pleroma, a kind of noetic fullness, and as the unity of all the gods (neteru). His function, at least in some respect, is analogous to the function of the Qur’an in Islamic and the Logos-Christ in Christianity.

In Neoplatonism this elevation is conducted both by philosophy (Platonic dialectic) and hieratic art (theurgy, sometimes regarded as Chaldean in origin). Proclus expressed this in the technical terminology of his rational and systematic philosophical discourse:

‘The elevation (anodos) of all intellective summits towards the inexpressible (aphrastous) and intellective powers is affected through the connective gods and by the theurgists. As the gods here (the intellegible-intellective) indeed connect to the primal intelligibles, which Plato no longer explained with words; for the connection to them is ineffable (arrhetos) and takes place through ineffables, exactly as the theurgists believe, the mystical union to the intelligible and primal-working causes takes place through this (intelligible-intellective) order. Therefore the way of elevation is the same with us (Platonists) and through this is the most faithful way of theurgical elevation’ (Plat.Theol. IV.28.221-29.5).

In order to understand Proclus, we ought to remember that he arranges the henads (the ineffable gods as transcendent unities) in a hierarchical order which prefigures the structure of the lower orders of reality. In general, there are higher noetic orders made of (1) intelligible henads (related to unparticipated Being), (2) intelligible-intellective henads (related to unparticipated Life), and (3) intellective henads (related to uparticipated Intelligence). In the terms of the Phaedrus’ myth, the noetic cosmos is divided into:

- The vault under the Heaven (hupouranios hapsis), which marks the first stage of the anagogic path that comes immediately after the Intellect (Nous) proper and is regarded as the beginning of the noetic mysteries (teletai) of real Being;

- The Heaven (ouranos) itself, which manifests everything below it and consists of three triads: the highest triad is called the fiery (empurios) back of Heaven, which is not visible to what is below and upon which the soul stands to contemplate the real Being beyond; and

- The place beyond Heaven (huperouranios topos) where the soul is granted the full mystical vision (epopteia) and where the primordial divine law (thesmos) is established – the law which maintains the whole reality below, as the Egyptian maat (truth, harmony, order, or spiritual path, its means and its goal). This topos is the eternal abode of knowledge-itself (autoepisteme), virtue or temperance-itself (autosophrosune) and justice-itself (autodikaiosune).

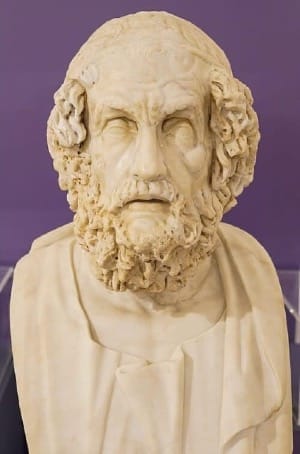

Theological revelations of Homer

Despite the monotheistic attempts to annex the truth and the way to the noetic realm of the divine Ideas (or Names), thereby restricting such terms as ‘revelation’, ‘divine inspiration’, and ‘prophecy’ to the dogmatic perspective of the single privileged community, and as a guard against imagined ‘paganism’, the above-mentioned terms can nonetheless be understood in much more universal sense.

The Hellenic philosophical traditions are not unanimous in how they respond to metaphysical, physical, and ethical questions. However, they generally regarded the poems of Homer as a more or less adequate and authoritative paradigm of the entire Hellenic culture. If ‘literature’ (the privileged texts, viewed as being ‘inspired’ by the Muses or the gods themselves) are seen as a possible source of truth, then it is clear why, especially in the Roman times, there is no clear distinction made between reading Homer as ‘literature’ and as sacred discourse (hieros logos), similar to the Orphic poems and the Chaldean Oracles (ta logia).

The Homeric heroes themselves (for instance, seers Theoclymenus, Calchas, Teiresias) are granted the direct perception of divine reality that may be termed ‘revelation’ or the epiphany of the gods. In later times, even the myth of Homer’s blindness is turned into a symbol of mystical vision (epopteia), of access to the higher noetic and supra-noetic realities. Thus an oracle calls Homer himself an ‘ambrosial Siren’ (ambrosios Seiren), though the problem of an adequate communication, Hermaic translation and proper interpretation still remains. ‘It is a hard thing for me to tell all things like a god’, according to the testimony of Homer (argaleon de me tauta theon hos pant’ agoreusai: Il.XII.176). It is safer to turn for assistance to the divine powers and pray or put a request accordingly:

‘Tell me now, Muses of Olympus – for you are goddesses, here beside me, and know everything, while we hear only reports and know nothing’ (Il.II.484-486).

Since Homer is regarded as the Hellenic theologian par excellence, his poems are thought to have both theological and scientific value. According to the ancient convention, all distinguished sages, inspired by the Muses and the gods, including poets, interpreters of sacred omens, oracles, and symbols, as well as hierophants and philosophers, such as Orpheus, Pherecydes, Aglaophamus, Pythagoras and Empedocles are hoi theologoi. When Aristotle speaks about ‘the theologians who generate everything from Night’ (hoi theologoi hoi ek nuktos gennontes: Metaph. 1071 b 27), he has the Orphics in mind.

The authority of Homer is emphasized even by the defensive tradition which stands against such critiques of traditional mythology as Xenophanes of Colophon and provides an allegorical exegesis of Homeric images. According to this view, which is attested within the Orphic tradition and related to Theagenes of Regium (c.525 B.C.) by Porphyry, Homer speaks allegorically (allegorikos legei). He says one thing, but means another (all agoreuei). Plato fails to understand this concealed ‘real meaning’. That is why he banishes Homer, along with the other imitators, from his ideal State on the grounds that he and other similar artists merely generate images that are ‘at the third remove from truth’ (tritos apo tes aletheias: Rep. 599d). But the traditional Hellenic paideia never followed the radicalism of Plato in this respect and the Stoics already acquitted Homer entirely.

In the broader context of traditional Hellenic culture, Homer is no less than a spiritual hero (‘spiritual’ in the strictly Hellenic sense), in some respects tantamount to the Egyptian Thoth, albeit modernized and humanized.

The Middle Platonic and Neoplatonic traditions also emphasized the spiritual and cosmological authority of Homer. When Porphyry refers to Homer as the theologian (ho theologos), he simply remains faithful to the ancient habit. According to Robert Lamberton, the early Pythagoreans regarded the Iliad and Odyssey as sacred books – as sources of both magical incantations and moral exemplars.[[3]] The Alexandrian Neoplatonist Hermeias (5th century A.D.), while following his master Syrianus, tried to show the inner meaning of certain Homeric and Orphic myths. ‘Mythology’, he pointed out, ‘is a kind of theology’ (he gar muthologia theologia tisestin). Therefore the main mistake of the uninitiated, according to Hermeias, is to ‘fail to grasp with wisdom the intention of the mythoplasts, but rather to follow the apparent sense’ (In Phaedr.73.18-21).

In the broader context of traditional Hellenic culture, Homer is no less than a spiritual hero (‘spiritual’ in the strictly Hellenic sense), in some respects tantamount to the Egyptian Thoth, albeit modernized and humanized. He is treated as the founder of an inspired theological discourse and the source of the entire Hellenic science, philosophy and ‘literature’, including history, rhetoric and various kinds of poetry. Truly a prophetic voice and avatara of the divine Intellect.

The Gods of the Hellenic Tradition

Proclus argues that Homer and Plato are each in touch with the gods and the supreme truth. However, they expressed the revealed divine realities (ta pragmata) differently. While Homer’s account of truth, as the result of divine mania, is inspired and therefore inevitably obscure, Plato’s discourse is more systematic and rationalized. In fact, Plato’s philosophy may be regarded as a commentary on the Homeric riddles and obscurities. Thus the inspired Homeric discourse stands closer to the theurgic mysteries and their ineffable symbols, addressed to the initiates. Though Plato’s interpretation (as would be of any ‘translation’ and hermeneutical elaboration) is further removed from the primordial inspiration, it nevertheless provides a more useful account of the reality that conforms to the ethical purpose of education.

Though human language (which is inevitably ‘allegorical’) does violence to the truth by presenting sequentially or in scattered manner what is simultaneous and unified in the divine realm, the Homeric poems may be regarded by pious commentators as microcosmic reflections of the mysterious archetypal world. The insights, symbols and images, shown in this obscure mirror of inspired ‘theological’ poetry and mythology, can be further clarified by the rational philosophical discourse at the level of discursive reasoning, or dianoia. Just as the poems of Homer are regarded as the source of all knowledge about the gods and human wisdom (including philosophy and science) by some Hellenes, so the Qur’an is maintained as the archetypal source of all knowledge, law and wisdom by every Muslim. However, at this point the important difference of the contexts and attitudes must be emphasized.

In ancient Mediterranean spirituality (usually labeled with stressed scorn as a ‘paganism’ by its enemies, especially Christians) there are no unanimously recognized, canonized and compulsory sacred texts or doctrines, at least comparable to those ‘marvellous books’, adored by the Semitic exclusivists, and their mandatory credos. Although many Hellenic theological and ethical paradigms, cosmological doctrines and spiritual practices are both read in and drawn from the poems of Homer, Hesiod, Orpheus and numerous Oracles as well as the texts of the eminent sages, the founders of the main philosophical haireseis (such as Pythagoras and Plato, who are likened to archetypal heroes), these poems or hieratic texts never play the role of the ‘Bible’. They are not regarded as the exceptional sources of the obligatory law, established by the superhuman king, once and for ever, in some literal fashion that rejects the diversity of other cults and traditions.

The inclusive Hellenic monotheism (especially that based on the Middle Platonic and Neopythagorean theological interpretations) recognized beyond the many gods (as many personalized and mythologized Names, or divine Ideas) the ultimate divine ground. According to John Peter Kenney,

‘The Homeric gods, which became constitutive of classical polytheism, were frequently seen as regular, focal manifestations of the more obscure power which is divinity itself. They constituted the foreground of the divine over against its deeper primordial background. This is clear in many aspects of the Homeric account.’[[4]]

The gods (theoi) may be regarded as manifestations of primordial divinity itself, just as the Egyptian Atum-Ra in the form of the rising Sun, or the scarab Khepera, manifests itself from the primordial transcendent background of Nun. The plurality of the gods (theoi, daimones, neteru) is like the plurality of solar rays that shine forth when Atum-Ra raises up from the primordial lotus.

The Archetypal and Revealed Qur’an

Though the Qur’an comes to confirm the previous messages, it belongs to the ‘scripture’ or ‘book’ (al-kitab) tradition whose distant origins can be traced back to the Accadian, Babylonian and Aramaic prestigious institutions characterized by the bureaucratic adoration of the written words, tablets and their magic properties. It sharply differs from the cultural and cultic paradigms of Hellenes, who until the end of the Assyrian empire remained at the margin of Eastern civilizations.

Muslim devotees speak of revelation (wahy) and the sending down (tanzil) of the Qur’an in a much more specialized and exclusive sense (with the obligatory political and spiritual consequences that follow) than any revelation and inspiration provided by the Muses, Apollo, or Hermes to the pious Hellenes. The Qur’an is regarded both as wisdom (hikmah) and truth (haqq) revealed in oral form to Arabs and by extension (soon accepted) to all human beings. The Book is guidance to the Truth, who is God, the ultimate revealer and spokesman of this Truth.

‘And We send down in the Qur’an that which is a Healing and a Mercy to the faithful’, says God in His Book (17:82). ‘These are the signs of the Wise Book, a Guidance and a Mercy for those who do what is beautiful’ (31:2-3).

Thus the blessed (mubarak) Qur’an heals every social and spiritual disease, provides wholeness, well-being and leads towards tawhid, or unity, which may be interpreted and understood in different contexts.

When the universe is seen as a manifestation (zuhur), irradiation, or self-disclosure (tajalli), and reflection of the divine Names and Attributes, this philosophical and cosmological conception is nothing but a new adaptation and prolongation of the Platonic theory of Ideas, itself based on the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian mythological patterns. The creatures of the universe are the manifestations of God’s Names and Attributes, as they are the material theophanies of Ptah (technikos nous) or the solar manifestations of Ra, according the ancient Egyptians. Therefore God manifests Himself as the cosmos, or the cosmic Qur’an (al-Qur’an al-takwini), and discloses Himself to His creatures through the written Qur’an (al-Qur’an al-tadwini), revealed by the Thoth-Hermes-like messenger, the archangel Jibrail. The Qur’an is understood:

1) in the primal metaphysical sense (as autozoon of Plato, kosmos noetos, the living Book of divine Names and Archetypes);

2) in the macrocosmic sense (as the visible ‘text’ of the created universe);

3) in the microcosmic sense of the revealed Book (as the special message received by the Prophet and at first transmitted orally, the written fragments of which constitute the canonized religious scripture and serve as a prototype of law and wisdom, liturgy and any spiritual practice).

God’s Names (or noetic Ideas) revealed in His self-manifestation known as His Word (kalam, or logos) are called the ‘recitation’, i.e. the Qur’an. The Names (that may be viewed in the Middle Platonic fashion as the thoughts of God) designate the very nature of Reality, the principles and tokens (ayat) of which are reflected in the revealed microcosmic text. Therefore, as Sachiko Murata argues, standing (albeit tacitly) on the axis of Platonic realistic ontology: ‘It is we and phenomena that derive from the names, not the names that derive from our speculation’.[[5]]

In addition, the glorious Qur’an is written in ‘a guarded tablet’ (85:21-22). This is almost the direct allusion to the Mesopotamian antiquity and its sacred scribes, later to be interpreted in the Neoplatonic manner. The divine tablets of knowledge in Sumer contain me – the principles of various things and activities, their archetypes and divine powers. According to the Platonizing Muslim commentators, the Tablet is ‘an invisible spiritual reality on which the Qur’an – the eternal and uncreated word of God – is written’.[[6]]

When the Pen, by which the heavenly Qur’an is written, is understood as the First Intellect and the Tablet as the Universal Soul, this aligns with Neoplatonism pure and simple.

The Pen, by which this divine logos is written, is interpreted as the Intellect (‘aql; Gr. nous), God’s initial creation which constitutes the noetic realm. Therefore all creatures in their latent and undifferentiated form are thought to be contained in the Intellect’s knowledge as ink present within the Pen. When the Pen, by which the heavenly Qur’an is written, is understood as the First Intellect and the Tablet as the Universal Soul, this aligns with Neoplatonism pure and simple.

In Neoplatonism, the Intellect is described as holding the One’s (i.e. God’s) light within itself. This light is broken into noetic fragments (or written on the Tablet) by Nous, resulting in the multiple unities which are the supreme archetypes or the Platonic Forms. The lower reality (be it a set of phenomena, ayat, or a collection of the Qur’anic ‘signs’ and ‘verses’, ayat again) is established and kept by the immanent presence of the higher transcendent reality. The image depends on its archetype. Such attributes and characteristics of the image as its unity, structure, truth and value depend upon the noetic reality (the set of divine Names) that is immanently present through the plurality of the image (eikon, surah). Thus the archetype is revealed through its image; the noetic Qur’an is mirrored in the plurality of earthly books written by the scribe’s pen and ink.

Theurgic Presence of the Embodied Book

The word qur’an, literally meaning ‘recitation’, derives from a root that has two basic meanings: to recite and to gather together. The first word of the Qur’anic revelation is said to be iqra’, an imperative meaning ‘recite!’

‘Recite! In the name of thy Lord who created the human being from a blood-clot. Recite! And thy Lord is the Most Generous, who taught by the Pen, taught the human being what he knew not’ (96:1-5).

both ‘incarnation’ in Christianity and ‘inlibration’ in Islam, in principle, repeat the ancient cosmogonical pattern

Therefore the Qur’an is first a recited Book which, according to the usual practice of Arabs, must be memorized and transmitted orally. Just as the Hellenic paideia includes memorization of Homer and other classical poets (who, however, are not themselves idolized or adulated), in a similar way Islamic education begins with memorization of the Qur’an, which is regarded as the summa of wisdom. Just as Strabo and the Stoics find in Homer an encyclopaedia of science (including physiology, geography, history) as well as theology, so the Muslims find in their Book a full encyclopaedia of the divine Names and legal wisdom, including that of al-‘alam al-kabir (the large world) and al-‘alam al-saghir (the small world). These terms themselves are the literal Arabic translations of the analogous Greek terms.

Though the Qur’an is identified with the divine logos itself, the Muslims avoid to talk about its ‘incarnation’. Rather they prefer ‘inlibration’ which means ‘embodied Book’: the Word becomes the embodied Book. However, both ‘incarnation’ in Christianity and ‘inlibration’ in Islam, in principle, repeat the ancient cosmogonical pattern. The clear parallel of this descent is the ancient Egyptian ‘animation’ of statues and temples along with hieroglyphs and painted images on the walls and sacred scrolls. This is the fundamental doctrine of both invisible and visible theophanies and the divine kingship brought by the living son of Ra (sa Ra) and his vital power (ka) which keeps the heart of every man and the entire landscape of theocracy.

In the traditional Islamic context, a recited Book (al-Kitab) is a Book that is embodied within human beings. This descent has cultic prototypes that were once almost universally recognized. The solar falcon Horus (or rather his ba) descends on his own statue, or image (sekhem), and the goddess Hathor flies down from Heaven in order to enter the ‘horizon of her ka’ here-below, i.e. her body, to be united with her image. Through reciting the Qur’an, every believer comes to embody book, thus becoming (directly or indirectly) a perfect and pure receptacle of the spiritual form, which is divine light and logos, in the same manner that the material principle functions as a receptacle (hupodoche) for the divine Forms in Plato’s Timaeus.

Similarly the gods habituate the souls of theurgists while still in bodies. For the Platonizing Chaldeans and Neoplatonists, every soul, at least in principle, is able to embody a return to the divine realm through the theurgic rites and symbols. As a rule, not only the human body, but the entire world can be seen as the receptacle and holy temple of the gods. In this respect, Plato, Iamblichus and any priest of Ptah in Memphis would agree. The incantations (hepodai) are among the divine symbols (sunthemata): certain melodies and rhythms (when the ineffable names of the gods are recited) allow the soul direct touch with the gods. For Muslims too, the sounds and rhythms of the Qur’anic recitation produce a direct ‘theurgic’ influence on the human body and elevate the soul.

Signs and Symbols of the Cosmic Text

As stated earlier, the text of the cosmic Qur’an, consisting of visible phenomena as symbols, signs, and tokens of the transcendent divine realities, is embodied in the cosmic creation.

‘We shall show them our portents (ayat) upon the horizons and within themselves’ (41:53).

Here the features of the ancient Egyptian and especially Mesopotamian cosmos, along with its meaningful signs and omens that require some interpretation, or hermeneutical analysis, are still recognizable. In Neoplatonism, these signs are sumbola kai sunthemata, symbols and synthems, which have an anagogic power that lead to the noetic Stars and to the One itself. They can be regarded as beautifully arranged images (eikones), assigned for contemplation as well. Therefore it is not quite true that the Qur’anic revelation ‘created’ an Islamic cosmic ambience or its semiotic horizon filled with the signs of God (ayat Allah). It created a community (ummah) of believers and re-created or simply re-interpreted and re-confirmed the most of old cosmological patterns and mental attitudes.

The eminent Sufi philosopher Ibn al-‘Arabi (d.1242) explains these Islamized cosmological patterns in a highly sophisticated and intentionally obscure manner. He argues that the very substance of the created cosmos consists of the Breath of the Compassionate (nafas al-Rahman) breathed upon the archetypal realities (al-a ‘yan al-thabitah). This nafas partly resembles Shu, the very Breath of Atum, the principle of divine Life, which along with Tefnut (maat, divine truth and order), constitutes the universe, according to the theological accounts of the 18th dynasty of Egypt. To a lesser extent it is like the all-pervading Stoic pneuma which later is turned into the more spiritual entity, pneuma hagion.

The Breath that issues from the Divine Compassion (the Name al-Rahman) thus becomes the very substance of cosmic phenomena, therefore every created (or manifested) thing praises the Lord through its very existence. Every creature is like a heliotropic flower which praises Helios by its very existence in Proclus’ account which describes the vertical chains (seirai) of Being:

‘What difference is there between the human manner of praising the Sun by moving the mouth and lips, and that of the lotus which unfolds its petals? They are its lips and this is its natural hymn’ (On the Hieratic Art VI.149).

This is a sort of universal prayer, the universal invocation (dhikr) of His Name, to put it in the Islamic terms. This is the same as to say that ‘all things pray, except the First’ (Theodorus of Asine apud Proclus In Tim. I.213.2-3).

Since the created order reflects the divine Attributes (sifat), all things bear the sign of God’s Oneness. All things are secretly founded on the ineffable unities (henads) that not only initiate the dialectical play of the One and Many, but also lead toward the supreme transcendent background of the Reality itself, while revealing the divine unity at every instance of creation. In Islamic tradition it is stated as follows:

‘In every creature there exists a sign (ayah) from Him, bearing witness that He is Unique’ (Wa fi kulli shay’ in lahu ayatun tadullu ‘ala annahu wahidun).[[7]]

The Qur’an itself is granted by a mysterious or miraculous presence, thus in its microcosmic complexity becoming like an untranslatable and unique sunthema. According to Iamblichus, naming, thinking and creating is one and the same activity of the gods:

‘The invocation makes the intelligence of men fit to participate in the gods, elevates to the gods, and harmonizes it with them through orderly persuasion. Whence, indeed, the names of the gods are adapted to sacred concerns, and with the other divine sunthemata they are anagogic and have the power to unite these invocations to the gods’ (De myster. 42.9-17).

The Golden Body and Image of God

In Islam, the quintessential prayer of the heart, or dhikr (which is frequently compared to anamnesis of Plato — whether that is well-founded or not is separate question) has its roots in the Qur’an and, in fact, is said to be the essence of its message. Therefore, in spite of the intellectual dimension of the Qur’an, it is praised as a sacramental body of the Word which transcends any rational and philosophical discourse. Instead it embodies the salat, or prayer, which consists of cyclic movements (the prescribed postures and gestures, that are like the cultic hieroglyphs of the body, the basic symbolic asanas of the entire community) and recitation of the Qur’anic verses.

In this way the Qur’an (as an immanent light of logos or a set of sunthemata) is embodied within the person who performs the prayer and who is transmuted by the divine Light, exactly like a cultic statue (Gr. agalma; Egy. sekhem) animated by the descent of the divine theophanies or the bau of the gods. The Qur’an becomes a sort of inner ontological reality of muhsin (the person who possesses virtue of ihsan) in his heart (qalb) which is the microcosmic mirror of the divine Intellect. Similarly in Egypt, the heart (ab) is a seat of intelligence and abode of truth (maat), where the vital principle (ka) is established as a daimon. The Qur’an also becomes the reality of person’s body. Remember, that the golden bodies are the bodies of the gods (neteru) which serve as an icons and patterns for alchemical transformation in the Egyptian mysteries.

Since the human body is itself sometimes regarded as a manifestation of Light, its purity can be restored and luminosity intensified by reciting the Qur’an, God’s own luminous speech. In this sense the Qur’an is Light (al-Nur). To embody the Book through liturgy and spiritual exercises, faith, love, virtue, and knowledge, is to enter the path of transmutation by the divine Light, the path of the alchemical ‘gold-making’.

The Qur’an is a full image (surah) of God, but a human being in his present condition is incomplete image and therefore he must bring all God’s attributes into embodied existence through his religious practice and through theourgia in its broadest sacramental and aesthetic sense to embody the Light of that image. In this integrating, unifying and anagogical task, the microcosmic Qur’an serves as an external model which, on its own level, reflects the entire noetic cosmos. In the same way the opening surah al-Fatiha is said to embody the whole of the Qur’an, and al-Fatiha itself finally may be reduced to a single letter, or so on.

Therefore, as Frithjof Schuon noted, the Qur’an can be likened to the world which is one and multiple at the same time: the world is multiplicity which disperses and divides; the Qur’an is a multiplicity which draws together and draws to Unity.[[8]] Understood in this way, the Qur’an contains both the doctrine and the method of Islamic spirituality; indeed Islam itself and all related metaphysical doctrines (as it is assumed following the idealized pattern which easily dismisses the complicated historical realities in favour of an archetypal mythology) originates in the Qur’an.

Homeric Discourse Turned into Platonic Metaphysics

If one would naively approve and accept the hermeneutical model articulated by Socrates in Plato’s Protagoras (347e), frustrations, similar to some radical conclusions reached by postmodernists, are almost inevitable. Socrates argues that we can never interrogate directly the author of the written text, therefore there is no possibility to test our own understanding about the actual meaning of the text and to prove that our inferences are coextensive with the real meaning intended by the author. This seeming puzzle concerns the problem of intersubjectivity and, despite its simplicity and logicality, it is a piece of discursive infantilism in its most literal fashion. Nevertheless, the so-called ‘intention’ of the author and the supposed initial ‘true’ meaning are two exegetical issues which (at least until the advent of postmodern criticism and deconstruction) governed the process of interpretation even in those cases when exegesis is turned into a sheer fantasy and ideological fiction.

In fact, the text itself sets the limits for its interpretation, and the Neoplatonists accepted this rule. In this particular respect they differed from the Stoics who sometimes explicitly approved the presumption that the interpreter, not the text, determines the field of reference, the allegorical relationships and, finally, the scope of meaning.

But if a text is considered as a more or less divinely inspired utterance or the direct speech of the gods themselves, it acquires a privileged status and value. Such a text requires not only some particular hermeneutical attitude, but also it must be interpreted according to strictly determined rules and principles sanctioned by the recognized spiritual and philosophical authorities.

The Neoplatonists, who regarded Homer as a theologian and searched for the esoteric meaning beneath the surface of apparent one, finally turned the poems of Homer into revelations of Platonic metaphysics, conceptions that deal with the structure of the noetic order and physical cosmos as well as the fate of immortal souls. The allegorical interpretation of Homer (in physiological, arithmological and mystical sense) is rooted in the early Pythagorean and Orphic tradition which, in its different branches and changing streams, extends from the 6th century B.C. to the 6th century A.D.

Pious readers of Homer in various Middle Platonic and Neoplatonic circles used the myths and philosophical doctrines of Plato to explicate the myths of Homer. Being convinced that both Homeric and Platonic discourses have similar structures of meaning and are aimed at the same metaphysical goal, they tried to show that Homer is the source of all philosophy. This confidence is close to the traditional Hellenic opinion that Homer stands at the beginning of various human skills and theological wisdom as such. So, for Longinus, Plato is a philosopher who ‘more than any other, channelled to himself a multitude of streams from the Homeric source’.[[9]] And Proclus quite boldly asserts:

‘For in this way both Homer and Plato may be revealed to us as contemplating the divine world with understanding and knowledge, to be teaching, both of them, the same doctrines about identical matters, to have proceeded from one God and to be participating in the same chain of being, both of them expounders of the same truth concerning reality’ (In Remp.I.71.10-17).

According to Proclus, the same doctrines can be communicated in different forms, and different hermeneutical methods (functioning at different ontological and epistemological levels) are to be used to explain the meaning of a text. Proclus maintains that Plato derived from Homer many of his doctrines, but expressed them in rather different way.

Primordially Revealed Truth

The Neoplatonists and the majority of Hellenes believed that the divine and human wisdom was revealed in its fullness by the gods (theoi, as the faces of the single transcendent divinity) at the dawn of civilization (in illo tempore) which marks the beginning of a certain cosmic cycle. The precedents of the ‘primordial time’ (sep tepi in the Egyptian terms) are the prototypes for any human action, religious practice, science and art. The mythic statements concerning the ‘primordial time’ or the paradigms (archai, paradeigmata) both do violence (as does any language indeed) to the truth. However, they provide the means for salvation. The sacred myths point to eternity:

‘These things never happened: they exist eternally. Nous sees all things simultaneously, but words express first some, then other’ (Sallustius De diis 4, p.8, lines 14-16 Nock).

Homer’s is one voice among the voices that utter a single perennial truth.

The subsequent ages obscured the truth revealed at the beginning which, however, may be constantly re-actualized (or simply imagined to be so) and re-constituted in the temple ritual. At certain intervals of historical time this truth is rediscovered and reinterpreted by inspired sages and spiritual heroes. Plato is among them. Therefore no wonder that he, according to Proclus, took over from Homer ‘all of his doctrines concerning nature’ in order to ‘bind them fast successfully with the bonds of irrefutable proofs’ (In Remp.172.6-9).

Thus Homer (who perhaps is just an archetypal legendary mask of several inspired poets or the entire guild) stands in the same chorus of traditional ‘avataras’ of wisdom, sages such as Orpheus, Pythagoras, and Plato. He is one voice among the voices that utter a single perennial truth. This point of view is confirmed by the Neopythagorean Numenius, who is regarded as a direct forerunner of Plotinus. He says:

‘[With regard to theology] it will be necessary, after stating and drawing conclusions from the testimony of Plato, to go back and connect this testimony to the teachings of Pythagoras and then to call in those peoples that are held in high esteem, bringing forward their initiations and doctrines and their cults performed in a manner harmonious with Plato – those established by the Brahmans, the Jews, the Magi, the Egyptians’ (fr.1a).

Numenius of Apamea viewed Homer as a fountain of the primordial revelation, comparable, as Lamberton has pointed out, ‘on the one hand with Pythagoras (who may have been seen by Numenius as a reincarnation of Homer, as he was by some Pythagoreans), and on the other with the wisdom to be gleaned from the Old Testament, from Egypt, and from Persian astrology’.[[10]]

In fact, Numenius goes so far as to identify the legendary Hellenic singer and mystagogue Mousaios, who is said to be a master of Orpheus, to Moses the Egyptian, the great Jewish prophet. This false identification seems to be invented by a Hellenistic Jewish historian, Artapan of Alexandria, who represented the political interests of the bellicose and envious diaspora and therefore tried at any price to derive all prestigious Hellenic philosophy and wisdom from spurious Jewish sources. in any event, the tradition of Homeric commentary (both its methods and vocabulary) has been adapted by Jewish exegetes of Hellenistic times. So, when Philo of Alexandria distinguished clearly between literal meaning (to rheton) and hidden allegorical meanings (allegoriai or huponoiai), he faithfully followed the example provided by Homeric and Orphic commentaries.

Secrets Behind a Screen

The inspired mythoplasts (creators of myths) are not clearly distinguished from the inspired interpreters of mythical accounts and symbols, and both may be regarded as hoi theologoi. Therefore texts can be easily twisted in a synthetic effort to reconcile any myth with a particular metaphysical or theological doctrine. The poets’ and mythoplasts’ distortion of reality is understood as a consequence of their efforts to project ineffable divine truths on the dim and obscure screen of human imagination.

the Homeric poems (and all traditional religious myths) are to be explained not according to the apparent sense (kata to phainomenon), but rather according to the secret theory or unspoken doctrine

Proclus’ defence of Homer against the attacks of Plato consists in establishing different ontological levels of language and exegesis. The luminous apparitions of gods in various shapes, epiphanies and revelations do not imply any change in the gods themselves, who are both henads and intelligible creative principles of all lower reality, but imply that different receivers (hupodochai) experience their images and apparitions differently, according to their capacities, predispositions and preparations.

The unspoken (aporrheton) doctrine is contained within the text of Homeric poems themselves and this doctrine cannot be encountered and understood by the uninitiated hearers and readers, who confine their attention to the apparent meaning. Therefore the Homeric poems (and all traditional religious myths) are to be explained not according to the apparent sense (kata to phainomenon), but rather according to the secret theory or unspoken doctrine (kata ten aporrheton theorian). Since Homer speaks ‘by divine inspiration’ (entheos: Procl. In Remp.I.112.2), his poems mirror or contain a set of inner meanings, or secret theoria, which must be articulated outside by a hermeneus who has a similar divine inspiration or insight and can explain the text according to its supposed inner sense. This inner sense is boldly equated with the late Neoplatonic metaphysics, regarded as philosophia perennis.

The apparent sense of the tale serves as a screen (parapetasma) which, at the same time, both reveals and conceals the secret metaphysical truth. Indeed, the lack of resemblance between the screen (an outer image or its surface value, to phainomenon) and the truth behind the screen is regarded as a guaranty of symbolic relationship:

‘Symbols are not imitations of that which they symbolize’ (In Remp. I.198.15-16).

Thus a close connection between the symbols of the inspired Homeric diction and the mysterious symbols of sacred rites and theurgy is established. Proclus linked theurgical powers with the very form of epic utterances and believed that the hexameter was invented for prophecy (apud Photius Bibl.cod.239).

In the philosophy of Proclus, the sumbola constitute the very structure of manifested reality and are related to their referents on higher noetic levels of being through the double chain of descent and ascent. Thus the theurgic symbol functions on different ontological levels as an immanent divine spark or token (sunthema, which in some respect may be analogous to an ayah of the Qur’an) that opens the secret door to its ineffable henad and to the One itself. To put this in Islamic terms, in the created cosmos (‘alam), every existent thing is a mark (‘alama) of God’s existence, power, desire, and knowledge.

Just as the Qur’an is recited to manifest the sacramental, protective and purificatory power of the logos, so the Pythagoreans used passages from Homer for incantations and spiritual (even medical) purifications. In theurgy, the audible sunthemata consist of divine names, hieratic verses and musical compositions that hymn the noetic light (to noeton phos) and lead the ‘true athletes of the Fire’ (Iambl.De myster. 92.13-14) to supreme union.

Imaginary Landscapes of the Logos

The imaginative world of mythological and theological texts, understood as a literary microcosm, may be likened to the cosmological dimension of autonomous images, granted separate existence by the realistic ontology. This is the same intermediate dimension (be it invented as a hermeneutical fiction or created by the imaginative perception of the divine and human phantasia) as Duat or Amentet of the Egyptians. So, according to al-Suhrawardi (d.1191):

‘When you learn from the writings of the ancient Sages that there exists a world possessed of dimensions and extent, other than the pleroma of Intelligences and the world governed by the Souls of the Spheres, and that in it there are cities beyond number among which the Prophet himself mentioned Jabalqa and Jabarsa, do not hasten to proclaim it a lie, for there are pilgrims of the spirit who come to see it with their own eyes and in it find their heart’s desire’.[[11]]

An imaginary landscape, created or simply perceived by the seer means that the ascending phantasia of the soul at certain point encounters the descending phantasia of the Demiurge. But this imaginative reality may be regarded as a semiotic reality of the cosmic ‘text’, since the spiritual journey through the Names, by the Names and to the Names is a semiotic journey taken by the soul-transforming ‘interpretation’ within the boundaries of divine Logos, tantamount to the manifested Being itself. This epistrophic movement involves the play of shifting identities and involves the essential deconstruction of the entire creation, understood as an outer manifestation of the divine Names.

The Emperor Julian confessed that ‘there are many plants in Homer more lovely to hear about than those one can see with one’s eyes’ (Misop.351d). For Muslims, the Qur’anic accounts of paradise surely are more lovely to hear about than similar pictures of earthly luxuries seen with one’s eyes and, as a rule, proscribed (at least conventionally) by the puritan Plato, who in this respect is followed by the majority of Sufis.

The crude literal sense, characteristic for the primitive mentality of venerated heroes and not too perspicacious prophets, rarely proves to be sound for the more sophisticated taste and critical attitude of the later generations. Therefore it is usually decided that the surface of a text, be it acceptable or unacceptable, indicates some deeper meaning hidden behind the screen (parapetasma) or the veil. Thus Porphyry argues as follows:

‘The poet’s thought is not, as one might think, easily grasped, for all the ancients expressed matters concerning the gods and daimones through riddles (diainigmaton), but Homer went to even greater lengths to keep these things hidden and refrained from speaking of them directly but rather used those things he did say to reveal other things beyond their obvious meaning’ (Peri Stugos apud Stobaeus).[[12]]

poetry about the gods must be read in the same way as statues (agalmata) of the gods are ‘read’, or interpreted

The premises and hermeneutical conclusions of Porphyry are based on the ‘wisdom of the ancients’ and the supposed perfection of Homer. He reasons that Homer should not have successfully built up the entire room of his mythical story without some divine inspiration and without shaping that creation after certain truths and realities. Those truths and realities, however, are not physical or historical ones, but that of the noetic order and belong to the transcendent realm. They are concerned with the first principles governing the structure of meaning through the all creation, including the inner structure and semantics of theological or mythological texts.

How are such seemingly sacred and obscure texts to be read? According to Porphyry, poetry about the gods must be read in the same way as statues (agalmata) of the gods are ‘read’, or interpreted. This important aspect of exegesis perhaps alludes not only to the hieratic iconography and symbolism, but also to the rites of theurgic ‘animation’. The images (eikones) of the gods in sculpture, painting, recitation and writing have an analogous structure of meaning. In the case of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, all these aspects constitute an integrity which unites the sacred web of semantics and sacramental presence of the ineffable divine power (sekhem) and magic (heka). Porphyry maintains that the verses created by ancient theologians function as the eikones of the gods and must be treated and explained on the same basis as the statues are treated, and this may include prayer, adoration, confirmation and animation.

A Little Shrine of Wisdom

When the hidden meaning behind the apparent one is accepted and related to the divine truth, which is spiritual and eternal, that implies some invisible reality behind the cosmic phenomena is being recognized. In more elaborated form, this metaphysical insight is articulated as the theory of Archetypes and Ideas, which may be closely related to the cosmogonical myths and rituals (which provide a foundation for the whole social, political, economical, and spiritual life) and science, especially in the ancient Mesopotamia, where all things and manifested entities (nam) were thought to depend on the sacred prototypes (me) that constitute the luminous ‘magical’ field of destiny (gish-hur), governed by the divine logos. This ‘written’ field or tablet of destiny is analogous to al-lawh al-mahfuz, the Qur’anic ‘guarded tablet’.

When the ontological levels of reality are multiplied, as in the later Neoplatonism, multiple levels of exegesis are also willingly accepted with the following hermeneutical consequences: if various levels of meaning contradict each other or appear contradictory, obscure, or seemingly absurd, this appearance is regarded as relatively unimportant. Any paradox is easy resolved by reference to a more simple, integral and primal metalanguage at a higher level of Being.

Since the human creature is viewed as a microcosm in all its complexity, this entails adopting multiple valid perspectives and modes of exegesis, and this hermeneutical strategy is similarly applied to interpret all creatures in the cosmos and also the intelligible realm itself. In the context of the macrocosm-microcosm relationship (attested in Pythagorean cosmology and in Democritus), the privileged literary text is viewed as a microcosm, or a ‘little shrine’ of wisdom. The later Neoplatonists very seriously accepted Plato’s famous assertion that a literary composition (logos) must resemble a living being (Phaedr.264c.).[[13]] Therefore, as the Alexandrian Neoplatonist of the 6th century, Olympiodorus, pointed out:

‘The best constructed composition must resemble the noblest of living things. And the noblest living thing is the cosmos. Accordingly, just as the cosmos is a meadow full of all kinds of living things, so, too, a literary composition must be full of characters of every description’ (In Alcib.56.14-18).

the text creates a ‘space’ for a spiritual journey

The cosmos is a visible shrine, or living statue (agalma), in which the eternal gods dwell, and by means of which they manifest themselves to the mortals (Tim.37c); therefore the living text as a microcosmic entity becomes a sort of mirror where the whole structure of reality is reflected. The Anonymous Prolegomena to Platonic Philosophy (sometimes attributed to Olympiodorus) argues:

‘As we have seen, then, that the dialogue is a cosmos and the cosmos a dialogue, we may expect to find all the components of the universe in the dialogue. The constituents of the universe are these: matter, form, nature (which unites form with matter), soul, intellect, and divinity’ (Anon.Proleg.16.1-6).

But if a literary text is a cosmos and cosmos, metaphysically speaking, consists of descent and ascent, of proceeding (proodos) and return (epistrophe) to the One, or God, then the text creates a ‘space’ for a spiritual journey. It becomes like a yantra of the Hindus. And the interpretation may be compared to the gradual unveiling, to the penetration through the screens, surfaces and barzakhs, until the last ‘membrane’ of Hekate is reached. This ascent is both a ‘scholastic alchemy’ and a sacramental rite, because, in the final analysis, the logos-field of a text (albeit on its restricted ontological level) is the very token of the divine self-disclosure through the cosmic creation. This is how the Chaldean Oracles describe the hermeneutical process:

‘For the Paternal Intellect has sown symbols throughout the cosmos, (the Intellect) which thinks the intelligibles. And (these intelligibles) are called inexpressible beauties’ (fr.108).

Those symbols serve as a means for the ascent and union. The sacred text itself, while reflecting the same archetypal structure on which the cosmos (agalma of the immortal gods) is built, functions as a hermeneutical ladder to the first principles. The ‘ideal’ picture, indeed.

In the domain of Intellect and Platonic Forms, ‘everything is in everything but in a manner appropriate to each’ (panta en pasin, all’ oikeios en hekastoi: Procl.ET103).[[14]] If this metaphysical rule of unity (henosis) in noetic multiplicity, according to proportion (analogia), is partially reflected in the inner structure of a literary microcosm, diverse propositions may be reconciled: each holds true in respect to its particular perspective, scope and level. In fact, the hermeneutical rule, first attested by Aristarchus, that ‘Homer in many instances explains his own meaning’ (hos autos men heauton ta polla Homeros exegeitai: Porph. Quaest.Hom.I.12) is proved to be valid by reference to the noetic plenitude.

the potential Intellect is actualized and perfected by contemplating the One, and the products of this vision are the multiplicity of Forms

The multiplicity of the noetic cosmos is equated to the contents of the divine Intellect, which contemplates the formless (amorphon) and infinite (apeiron) One. The actualization of Intellect is the primary instance of the One’s final causality: the potential Intellect is actualized and perfected by contemplating the One, and the products of this vision are the multiplicity of Forms, i.e. luminous intellects and beings (cf.Plot.Enn.V.3.11-15). In certain respect, one luminous entity mirrors any other, therefore one piece of a text can explain another piece, and the text itself constitutes an integral unity, directed by a single scope, or ‘target’ (skopos).

Owing to such supposed archetypal unity and symbolic integrity, the Qur’an is also regarded as the best commentary upon itself. The exeegetical rule that a part of the Qur’an explains another (al-Qur’an yufassiru ba’duhu ba’dan) can be applied to all levels of interpretation.[[15]] The Anaxagorian and Neoplatonic principle ‘all in all but appropriately’, which later governed traditional Islamic hermeneutics in many respects, is systematically elaborated by Proclus. According to Lucas Siorvanes:

‘With it, he can formulate a general law for the plurality and diversity of beings and phenomena, causes and effects, qualities and meanings, while retaining their speciality. Moreover, the same thing can be conceived as existing on many different levels, each with its own distinct character. The advantage of this approach is that it makes analysis possible. A thing is not an opaque indivisible, but composed of a bundle of levels and modes. The same thing, be it a metaphysical entity, a piece of knowledge, a moral definition or a literary text, may possess diverse properties or have different meanings. It all depends on the level of analysis. Indeed, for Proclus, analysis marks the ‘return’ to one’s own-household simple principles and ultimately to the prime unity’.[[16]]

Divinely Inspired Myths and their Exegesis

For the Neoplatonists (as was the case long before them for the Stoics, the Pythagoreans and the Orphics), the Homeric poems had become a source of symbols, parables and allegories for the spiritual journey.[[17]] The Hindu Mahabharata also proclaims that there is nothing in the universe that is not included in its text, and it seems that such claims can be traced back at least to the Sumerian epics. Thus Odysseus (as in the case of Hindu Rama, who is the mantra of the Atman)[[18]] is regarded as the symbol of man escaping the physical universe, the Poseidonian Sea. Guided by the goddess of wisdom, Athena, Odysseus tries to return to the noetic realm for the re-union with Penelope, who represents the hidden spiritual powers of Odysseus himself. He desires to restore the peace of the Atman, speaking in the terms of the Hindu Ramayana.

The critique directed by the Sophists and Plato against the ancient mythoplasts and their creations is off-target, because, in this case, the symbolic contents of ‘more divinely inspired’ (entheastikoteroi) myths, reserved for the initiate, are utterly neglected. Such myths are to be interpreted according to the ‘hieratic customs’ that distinguish two separate ontological dimensions: ‘here’ (entautha) and ‘there’ (ekei). When Homer depicts the gods at war, for instance, he speaks of the increasing fragmentation of the descending divine irradiations and influences, which constitute a simple unity at their initial monads, but are divided as they proceed down to the encosmic orders of angels, daimones and heroes, thus sinking into the material cosmos, or the Sea of Poseidon, filled with storms and tumults. Although certain classes of the gods (say, divine Names) proceed from their appropriate monad down into the cosmic theatre, the Olympian Zeus does not enter into the strife, because the monad remains firmly established in itself, according to Proclus (In Remp.I.90.19). The theomachy (the fight of the gods) is turned to be an account of creation, the sacred cosmogony.

In the later Neoplatonism, traditional Homeric gods are equated with transcendent unities, or henads, arranged below the level of the supreme Monad (the One, which is everywhere, as well as nowhere, and for description of which the Plotinian phrase ‘as if’ must be added) and the generative Dyad (the Mother of the gods) of the Pythagorean cosmogony. Hence, such theological and cultic names as Athena, Hermes, Poseidon or Hephaistos may refer to many different ontological and epistemological orders. The divine chains proceed through the entire hierarchy of manifestation:

‘For each chain bears the name of its monad and the partial spirits enjoy having the same names as their wholes. Thus here are many Apollos and Poseidons and Hephaistuses of all sorts, some of them separated from the universe, some distributed through the heavens; some preside over the elements in their totality; some have been assigned authority over the specific elements’ (Proclus In Remp. I.92.2-9).

Therefore the names of the gods (theoi) refer not only to the ineffable henads at the beginning of each ‘golden chain’, but to all the members of any particular procession, or the ray of theophany. All henads originate from the One through the different ‘additions’ to the One which specify and multiply them. The attributes of the One, neglected by the first hypothesis of Plato’s Parmenides, are affirmed by the second hypothesis and thus constitute the ontological hierarchy from the intelligibles (ta noeta) to the encosmic entities. The higher may stand for the lower, since finally ‘all opposition must end in mutual harmony’ (Proclus In Remp. I.95.21-22).

The poems of Homer are interpreted accordingly. Thus Proteus is understood as an angelic intellect in the chain of Poseidon. Proteus ‘contains in himself the Forms of all things in this world’ (ta eide panta ton geneton: Proclus InRemp.I.112.28-29). Homeric Eudothea, interpreted as one of the disembodied daimonic souls, belongs to the same chain, but is established below the Protean level and contemplates the Forms of all things through him. However, the fragmented and ignorant soul is unable to perceive this angelic nous and the Forms it contains in a single simultaneous unity, therefore Proteus appears to pass continuously from one eidos to another. Exactly as ‘history’ runs. This allegorical motif may be viewed as a paradigm for hermeneutics. Indeed, unity (henosis, tawhid) seems to be multiplicity (the chain of being) when seen through the lens of ignorance. Therefore the main task of interpretation is to remove all veils and lead the strengthened and purified soul (Odysseus) to the safe harbour.

Interpretations of the Qur’an

Now let us turn to metaphysical, cosmological and ethical interpretations of the Qur’an. The basic premises of symbolic commentaries upon the Qur’an consist in acknowledging that the Book is both the Word of God and the most direct Symbol of the transcendent realm. The Book confirms the Oneness of God and reveals unity (al-tawhid) in multiplicity. As we know already, unity is the most important concept in Neoplatonic thought and without Oneness the universe could neither be nor be comprehended. Therefore:

‘If in the world at large every element partakes to some degree of Oneness, so, too, in the literary microcosm, every element, however seemingly trivial, is significant because it arises from the unified source of the work’s being, that is, the author’s controlling intellect, and must be interpreted accordingly’.[[19]]

In a single cosmos, one single Book can become a mirror of divine Oneness. Seyyed Hossein Nasr maintains that the whole of the Qur’an is a singular litany with the refrain of la ilaha illa’ Llah and is a commentary upon the truth of Unity (al-tawhid) contained therein.[[20]] As the Mother of Books (Umm al-kitab), the Qur’an is the origin of all Islamic spirituality; therefore Qur’anic verses are interpreted to legalize or to prove (just as in a similar way the Neoplatonic doctrines are deduced from Homer or from Plato’s Parmenides) that various metaphysical conceptions, especially those proclaimed by the Sufis, are not derived from a particular group (say, from Gnostic, Hermetic, Platonic, Peripatetic sources), but are already contained in the pleroma of the revealed Book, even if as obscure allusions to be elucidated by ta’wil.

However, despite this a priori accepted ‘archetypal idealism’, the methods used by Muslim exegetes tacitly depend on rules of exegesis practiced by the Christian and Hellenic exegetes in those areas that later became political and intellectual centres of Islamic civilization. For instance, Origen, himself a faithful follower of Philo and other Middle Platonists in respect of exegesis, maintained that Scripture is a book closed with seven seals. So, its obscurity (asapheia) is intentional, because the divine Spirit who speaks through the authors of the sacred books has a twofold auctoris intentio and must be understood (1) according to his primary skopos, as hiding a deeper meaning behind the surface, and (2) according to his secondary skopos, addressed in an accessible way to simple-minded people.[[21]]

In Islamic tradition, as in the Neoplatonism of Proclus, the ultimate goal of esoteric, or symbolic, interpretation (ta’wil) is a spiritual realization (the home-coming) through interiorization of the divine Names or the essence (dhat) of the Qur’an. The term ta’wil, recently made well-known in the West by Henry Corbin, means to take something (a text) back to its source, or origin (awwal) to attain its meaning. Consequently, to practice symbolic interpretation is to reverse the cosmogonical vector and to follow an epistrophic and anagogic path to the first Principle. Symbols are traced back to what they symbolize, images are carried back to their spiritual archetypes. According to Denis Gril:

‘Ta’wil is the masdar of the verb awwala – to make something reach its end; it is the factitive form of ala-y’ulu – to reach its end (ma’al). The same Arabic roots often carry opposite and complementary meanings, and this root is also that of awwal – first, or, beginning – which confers on ta’wil a meaning at once eschatological and cyclic’.[[22]]

The Qur’an is not simply a collection of scattered signs, because it is accepted, as a rule, that the symbolic structure of the Qur’an is ordered at all its levels, like in the Neoplatonic system of exegesis, which established a unity of parts and a unity of levels for the same textual datum. In the words of Hermeias:

‘Why is it necessary for the discourse to be unified? It is because in every thing the beautiful and the good desire its illumination from the One. For unless it is possessed by the One, such a thing cannot be good. So, also, beauty cannot be beautiful unless Oneness is present in all of its parts’ (In Phaedr.231.6-9).

Qur’anic symbols are not conventional signs, but exist independently of our understanding. Therefore they lead back to the higher realities they symbolize.

The operations of ta’wil are subject to the Neoplatonic metaphysical premise that every differentiated element within the structure of the cosmos (or a text) not only derives its symbolic reality from the One, but also has a secondary relationship of relative superiority or inferiority according to the degree of Oneness it partakes. It is regarded that the Qur’anic symbols are not conventional signs, but exist independently of our understanding. Therefore they lead back to the higher realities they symbolize. In an exegetical context, the distinct stages of meaning are the distinct stages (maqamat) of spiritual journey.

The hermeneutical structure of this relationship depends upon qualitative analogies among things that are discerned (or ‘imagined’) due to the accepted classifications and established correspondences between the macrocosm and microcosm, or the horizons and the souls (al-afaq wa’l-anfus). Therefore every manifested divine Name or Attribute exhibits in varying degrees the same characteristic throughout the entire cosmic hierarchy, exactly like the Hellenic gods and intelligible entities that constitute different descending and ascending chains (seirai).

These Names designates the very nature of Reality and produce the multiplicity of things which have their form (surah) and meaning (ma’na). It has been demonstrated by contemporary scholars that the doctrine of the double nature of speech, advanced by the Stoics, is reflected in Arabic grammar. Accordingly, outer speech (lafz) contains (both conceals and reveals) inner speech (ma’na), which may be understood as an immanent counterpart of the noetic Idea, reflected in the mirror of human intellect (‘aql, or nous). The correlation of and ma’na legitimize (and itself is based on) the ontological and epistemological correlation of zahir (outer reality) and batin (inner reality, regarded as haqiqah). As a logical consequence, two kinds of exegesis are established: tafsir and ta’wil.

The crucial distinction between the visible outer images and their invisible inner ideas provides two modes of existence for the whole created or manifested cosmic order: for all phenomena, all speeches and texts. This is a doctrine philosophically articulated by Plato, further elaborated by the Middle Platonists and directly or indirectly supported by the theory of the cosmic sympathy, made explicit by Poseidonius, but is clearly based upon the ancient Mesopotamian science of ‘the properties of the stars’ (ahkam al-nujum). Since the whole has priority over the part, the invisible inner reality is regarded as universal and is thus related to the transcendent realm of the Names, or Platonic Ideas, which constitute the living Paradigm of creation.

According to the hadith of the Prophet: ‘To every true being there corresponds a profound reality (haqiqah)’. The Iraqi Sufi, Junayd (d.c. 910) quoted it as follows: ‘every word has its profound inner truth’ (li-kulli qawl haqiqa).[[23]] The inner reality, or haqiqah, is that a thing or a person must achieve as his true nature, his innermost self, his archetypal identity. We ascend from one level of forms to another, until we arrive at the level of real existence (ta ontos onta: Proclus In Parm.901). This anagogic task is accomplished by the ta’wil. Revelation itself is a form of veil (surah hijabiyya), therefore to ripen for ta’wil, or unveiling, means to make ready oneself for a spiritual journey (safar) through the ontological stations and states of the Book. These stations correspond to the stations of the soul.

As with the ritual procession at the ancient temples, the spiritual and textual journey must be in accord to the rules of adab, a royal etiquette of the Oriental court. It presupposes the servant’s ‘heart’, as a microcosmic receptacle of the divine Word, where all the Ideas may be mirrored and re-united.[[24]] Therefore the spiritual pilgrim (in order to fulfill the ancient Platonic ideal of homoiosis theo) must conform himself with the virtues of the divine Names (al-takhalluq bi-asma’ihi).

To demonstrate the relationships established between the higher, intermediate and lower levels of being, all governed by adab al-haqq, or between the descent of the Qur’an and the Prophet, Denis Gril argues:

‘Adab (...) is the way of perfection, incarnated by the Prophet, and founded on the distinction of servant and Lord, instituted by the haqq of Revelation. Moreover the whole proof of this rests on the meaning of ‘bringing together’ tied up in the root jm’, a meaning also included in the roots qr’ and ktb from which are derived qur’an, recital or reading, and kitab, wing and book; and thus both modalities, oral and written, of Revelation’.[[25]]

Therefore the spiritual traveler, or hermeneus who practices ta’wil, may be compared to a tax collector, ordered, for the glory of God, to bring together all elements that constitute ‘truth’ (al-haqq), by which the things are created, or the Muhammadan Reality, equivalent to the Neoplatonic kosmos noetos, that is established. Thereby ‘knowledge’ and ‘being’ are re-united in the divine Presence through the theurgic power of the Book.

Final remarks

Certain typological parallels and even literal identities between Neoplatonic hermeneutics and esoteric interpretations of the Qur’an are explored here not for the sake of the contest (agon), which always too easily captures the minds of those who belong to different traditions and who wish at any cost to prove that the sun they observe is the only true sun.

So far as the theory of archetypus mundus, in any of its historically attested forms (be they mythological, philosophical, theological, or simply psychological), is regarded as valid, supplying a fundamental premise for ontology, epistemology, soteriology, and sacred art, the gates for ‘perennial metaphysics’ are open. The quarrel over its details does not matter as much as some rigid followers of the letter and guardians of purity might allow themselves to imagine.