I

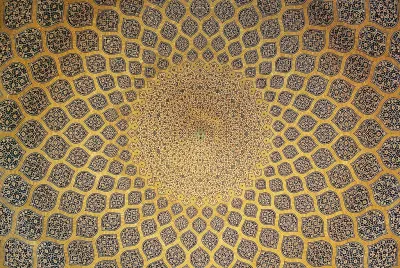

In light of the Absolute, the entire universe is a perfect harmonious whole, an All-in-One. In Buddhism, this ultimate principle is called Tathatā in Sanskrit, meaning Suchness or Thusness. It is the Supreme Reality, uncreated and unchanging; it is how things actually are in themselves, undistorted by our unenlightened subjectivity. Tathatā cannot be grasped as an object of our sense perceptions, nor is it conceivable in our minds. It can only be perceived by means of prajñā or transcendental wisdom, the attainment of which constitutes Buddhahood. An Awakened One apprehends Tathatā in the true sense of the term, in that they become indissolubly united to it. This wisdom gives rise to an undiscriminating love and a universal compassion – it is Tathatā in action, which ceaselessly acts on sentient beings to have them know the Deathless.

All things are encompassed, and pervaded, by Tathatā. The Absolute abides in the relative, and the relative in the Absolute. Likewise, we are essentially not other than the Buddha, for the latter is immanent in us as buddha-nature, which is what drives our aspiration for enlightenment. Thus, humanity’s spiritual propensities can be reduced to this indwelling presence, and our steadfast pursuit of goodness and truth will inevitably bring us to the realization of Buddhahood.

There are two paths that lead to this goal: the way of self-power (jiriki), and the way of Other-Power (tariki). The former provides methods for our personal cultivation and spiritual growth, chiefly by means of meditative practices. When undertaken properly, these help to unveil our true self; they can foster wisdom and nurture prajñā, by which Tathatā is directly intuited. Meditation is easy to start with, but difficult to accomplish. We are so full of defiled passions that contemplative serenity is rarely achieved. One moment of calm reflection can be quickly followed by turbulent surges of emotion. Therefore, according to the requirements of this path, if our meditation is not successful, enlightenment will remain elusive.

The way of Other-Power is based on the dynamic working of Amida, who is the Buddha of Immeasurable Light (Amitābha) and Immeasurable Life (Amitāyus). These are the two essential qualities of Tathatā in its vital aspect. The person of self-power confidently strides towards Buddhahood. On the path of Other-Power, however, the Buddha reaches out to man; pervading our hearts and minds, and transforming us into renewed beings. Amida freely gives us his wisdom (light) and compassion (life). No conditions are attached to this gift, which no amount of practice or prayer on our part can generate. In fact, our own efforts should be set aside, because they are tainted by attachment and delusion. This only serves to impede the working of Other-Power, which is solely dedicated to our release from suffering. Even ordinary faith, when understood as mere ‘belief’, is of no avail because it too is sullied by egotistic grasping. In fact, there is nothing we can contribute to our own salvation. We have only to receive what is given, and abandon our entire selves to Amida. This is the mind of True Faith.

II

The Mahāyāna speaks of the Buddha’s three bodies. The ‘Body of Dharma’ (Dharmakāya) is Tathatā itself; the omnipresent and immutable essence of reality. In its dynamic phase, it spontaneously takes form as Saṃbhogakāya (‘Body of Bliss’) and Nirmāṇakāya (‘Body of Incarnation’). The former is the transcendental embodiment of the virtues inherent in Tathatā. Its many manifestations (including Amida) can be visualized in profound meditation, and its spiritual power is also tangible to devotees of deep faith. The latter body comprises the countless physical transformations assumed by this reality (such as historical buddhas and bodhisattvas) in order to save sentient beings.

For example, Shākyamuni (the human Buddha), taught people how to break free from the cycle of birth-and-death (saṃsāra), and provided guidance in the various methods required to do so. From the perspective of Shin Buddhism, however, his instruction in self-power disciplines was only provisional as it paved the way for the Other-Power teaching, intended for those with greater spiritual maturity. In other words, Shākyamuni came into this world to fulfill the compassionate will of Amida. Initially, his earthly mission was to have followers accept Buddhist teachings of a more conventional nature, before disclosing the deeper doctrines concerning Amida’s liberating vows (to those who could see the impotence of their false self).

Another manifestation of Amida’s working is his Pure Land, or the realm of Sukhāvatī (‘adorned with bliss’), which is none other than a concrete expression of the formless Tathatā, revealed for the sake of beings afflicted by sorrow and ignorance. This divine will took the form of certain vows, the power of which gave rise to, not only a land of perfect ‘peace and happiness’ (anraku), but also to Amida’s Name which embodies the very substance of enlightenment itself. In other words, the Name conveys the salvific force of the Buddha’s resolve to bestow emancipation on all beings, and transfers the virtues of Tathatā to aspirants who invoke it with faith. This naturally brings about our deliverance in the ‘Land of Bliss’ at the time of death, where one’s eye of prajñā is completely opened, so that ultimate reality is seen as it is. Nirvāṇa is then attained without impediment.

III

Faith in Shin Buddhism is not understood in the everyday sense of that word because, in this case, it is an awakening conferred by Amida. Yet this may prove very difficult to accept, insofar as we are habitually attached to our limited intelligence and abilities. Even so, Other-Power faith can be effortlessly realized when aspirants heed Amida’s call without any doubt or hesitation, just as a child puts wholehearted trust in its mother’s unwavering love.

Amida summons all sentient beings, saying “Come to me at once! Do not be afraid of the transgressions you have committed. Do not fear falling into the river of fiery anger or the abyss of greed. I will protect you and lead you to safety. You are my children and I am your father. I have everything to give you. Hasten quickly to me!” We are simply urged to surrender, unreservedly, to the Buddha of Immeasurable Light and Life. We should not lament our lack of merit or wisdom, or grieve over our debilitating karma. Amida saves us exactly as we are, in whatever condition we happen to find ourselves.

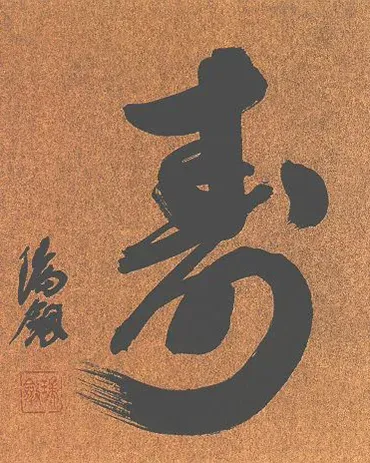

The Reverend Saizo Inagaki (1885–1981) was ordained a Shin Buddhist priest in Kyōto on the very last day of the Second World War in August 1945. A remarkable and charismatic teacher, his exuberant expositions of the Dharma attracted a large following, and there soon developed a widespread affection for him as a lucid thinker and compassionate minister. Inagaki Sensei spent his working life as the principal of a senior secondary school for girls in Kōbe. Having published more than twenty books in English and Japanese, he was one of the first Shin masters to actively reach out to Western audiences.