The sound of the woods sighing at the passage

Of the South-West wind is a wave that breaks

Gently, joyously, jubilantly into birdsong;

And from the green glimmerings and green shadows,

Up-and-down, with eddying, meandering flight,

The first butterflies come forth to the sun,

Tokens of immortality long treasured for this hour

— (Martin Lings, excerpt from “Spring-Summer")[[1]]

A breath: and in the height of heaven leisurely follows

Cloud upon cloud, and on the earth there has begun

A waking and a whispering, as ripples run

Over the green grass and the water of field shallows.

— (Martin Lings, excerpt from "The South Wind")[[2]]

How does a mystic approach the felicities of his poem: does he do so from the side of poetry, or from the side of mysticism? Martin Lings, a mystic born and a poet learned, always approaches from either side, from what to us, who are not by and large mystics and poets, is the yonder side. All his approach was by his twofold capacity of a Poet-Sufi. Of few assuredly is this so true. Approach is so significant of provenance and premeditation, so imbued with spirit and character, so full of memories, so etched by inspiration uncovenanted, so significative of cloistered life, that it confesses a soul’s history in a poem. In Lings’ poems, approach is subtle, so delicate and humble its withholding, yet his flight of song is as perceptible as a quartering wind, and as palpable. His flight of song crowns the heights and the depths of his mystical experience; the closet history of his numbers, and their conspicuous secret.

Lings’ book of verse enshrines, no word less solemn would be suitable, the early and the later in-gathering of his spiritual and poetical harvest. But it must be owned that Lings himself distinguished, though never separated, the poetry he composed before his initiation into Sufism and the poems he composed afterwards. Of his spiritual experience, of all its history, development and significance, his poetry was a signal fruit, full blown in the flower of his artistic perfection. This is to be insisted upon, because poetic art was uppermost in Lings’ mind. His is the quality of poetry that is not strained, a spirit that bloweth whither it listeth. Further still, he is always an artist, and considering the physics of the spirit’s flight before unfolding its wings is one of the prime notes of his versification.

Lings was hardly, in the wonted sense, a literary poet, because harbouring a white passion[[3]] for poetry as he did, he passed beyond and through literature. He cited no beautiful phrase for its mere beauty, but because for him it was true, and bore witness to a truth that his heart enclosed: the truth of his mysticism. To him poetry was art of the highest order. As to his own poetry, he used the technique of his art to clothe his mystical message in words and cadences poetical. Yet ‘to clothe’ is an expression precisely amiss. It should rather be ‘to incarnate’. For him, the import was divine and the words were living flesh and bone. Yet to say so much; to say that he was no literary poet in the usual sense, is not to deny his educated and keen delight in versification.

Lings grew ever toward a completeness in which his poetry and his spirituality were blended into a harmonious whole as inseverable as the colour and scent of the lilies of the field.

Manifest in Lings’ poems is what he achieved in the intimately poetical technique of metre, which for him was the spirit as well as the body of poetry. Let it be noted that when he introduced his poems, he spoke of their metre. While judging a poet’s work, one can hardly do otherwise than consider his technique more or less separately. It is the art that comes home to one, dividing soul and spirit. To some readers it may appear a paradox , nonetheless it seems to be an important fact: that the higher the poetry the greater in significance is what, with lesser works, would be termed the ‘mere form’. In poetry of the highest order, the versification, the form, is the very Muse. Lings’ versification proves him an artist. His Muse walks to the reader’s vision in light[[4]]. And it seems to be by a sense of light, the light of his spiritual growth, that one appreciates his Muse.

Lings’ spiritual experience comes, confessed, altogether to light, incarnate in the definite form of his lines; their metres, their words, their pauses, their accents and their movement. His verse is keyed to his spirit; they are of a piece. Lings grew ever toward a completeness in which his poetry and his spirituality were blended into a harmonious whole as inseverable as the colour and scent of the lilies of the field. And these, Jesus said, toil not, nor spin, but unfold into a perfection of beauty to which even Solomon in all his glorious array could not attain. His development, spiritual and poetical, was a process.

It must, nevertheless, be conceded that the word ‘development’ is used here under protest, because English language did not supply another word more proper and specialized. If this word have any exact acceptance, it must rather denote an interior force than a particular training or a lessoned cultivation. For Lings’ poetic development had always lain primarily in the perfecting of his soul. His refinement was created from within. The reader of Lings’ poetry is all the more privileged to trace his spiritual development outlined, enclosed, compressed and complete within his lines, for one paramount reason: He did not revise in maturity the poems of his youth, and brought no later treatment to bear on his early numbers. Keeping was vital to his art.

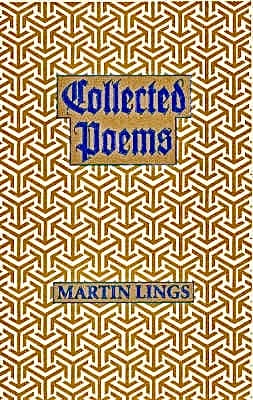

In little sheaves of poems, Lings garnered the harvest of his spiritual experience, which he sunned in publicity in his book Collected Poems: Revised and Augmented (2002). It comprises six sonnets and a narrative poem he indited before his initiation into Sufism, and twelve poems afterwards. Beauty was their binding thematic thread: the single rapture of his various song; beauty as splendor veritatis, Truth in its glorious light. Not without thoroughly conscious art did he bring to the light of verse his vision of Beauty. Obviously to say so much is not to imply that he discerned Beauty as one form whereby his soul expressed itself. He rather discerned it as the Form; the ultimate and perfect expression that is alchemically, substantially and harmoniously identical with his soul. Such vision as his cannot be searched nor dissevered from itself by a mental process, for it is the fruit of intuition; a thing never to be evidenced but always to be revealed.

Hence, the following is an endeavour to study Lings’ poetry as the consummate disclosure of his spirituality. His mysticism is the archetype, his poetry the symbol. His spiritual experience may be imaged to an archetypal magnet, his poems to symbolic magnetic fields drawing into their energy spheres accordant poetical material. For it would prove an error to suppose that by accident his metrical compositions ramify, and without an ordering principle. His developing spiritual life is what sets his thoughts into living and fresh moulds of ordered verse. What is intended is to show how, in Lings’ development as a poet, the development, formal and thematic, was significant of every spiritual phase through which he had passed. The form of his early and later poetry, in especial his metrical composition, encloses, implies, locks and answers for his spirituality.

Early poetry

The young Lings enclosed in his heart a master passion for poetry, inwrought with his instinct for worship and sanctity. His book of verse holds leaves wrung out of his soul’s record. In his preface, he quotes Keats: “poetry should come as naturally as the leaves come to a tree, or it should not come at all. By this he meant that true poetry comes out of the very substance of the poet as the leaves come from the substance of the tree or as the spider’s web comes from the spider’s own body”.[[5]] In Lings’ yeasting youth, Keats was leaven to his imagination. In equal measure the Romantic poet belonged to his spiritual and poetical history: he was a kindred soul. Thus he exercised his Muse in his verse. In his poem “The Muse”, The first opening line: “When she approaches, her immortal presence wakes me”[[6]] is composed after the iambic Fourteener of George Chapman’s Iliad. It reflects Keats’ sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” and his “Lines Written in the Highlands after a Visit to Burns’s Country”, where he conveyed in seven-footers his heavy walks among the Highland mountains.

The effect of Chapman’s verse upon Keats, when he felt like “some watcher of the skies/ When a new planet swims into his ken”,[[7]] is rehearsed in the effect of the approaching Muse upon Lings. Not unlike Keats, Lings felt the heavenly visitant breaking in upon him in the thick of affairs; her “unearthly motion made upon the air”.[[8]] When she comes unheralded, he extends the line to fourteen syllables. When he describes her movement, he does it in Alexandrines. His parsimonious Muse approaches by measure, and moves by canon, from which she takes a gentle liberty. Lings did not write his Alexandrines after the French custom, with a caesura midway. For his sustained lyric flight, an Alexandrine so partite had not unity. He wrote his not after John Dryden’s Alexandrine, but after Abraham Cowley’s, and no two verses may differ more in essence than Dryden’s bipartite line and Cowley’s most characteristic six-footer.[[9]] In the verse “to feel unearthly motion made upon the air”, one notes how Lings forestalls even an inadvertent pause, having the middle of the line fall mid-foot, unyielding to pause or even delay.

Lings’ six-footed line is nothing like the Eighteenth-Century practice of the Alexandrine, “whether ornamental or licentious”, which Dryden considered “as elevated and majestick, and has therefore deviated into that measure when he supposes the voice heard of the Supreme Being”.[[10]] Lings must have reckoned that the French middle break was intrusive in the English line rather than integrated into it. He must also have reckoned that, with a break midway, the lyric flight would exhaust the line, which, without it, would become suppler than the heroic and less suitable to dramatic poetry; a line capaciously lyrical. Although it had ruled but little in English poetry, Lings held to the lyric promise within the Alexandrine and had a precise concern that the long wand of his six-footer should not cede to the middle break, that it should be supple, vigorous and should last. It would not be much to maintain that the pace and majesty of the heroic Alexandrine are owed to the middle caesura that Lings had none of when he handled the line at its best. The French Alexandrine has two hemstitches, filling up two trimeters, with a break after the third foot. Samuel Johnson remarked that the measure of Robert of Gloucester taught the way to the French Alexandrine. In it,

sometimes the measures of twelve and fourteen syllables were interchanged with one another. Cowley was the first that inserted the alexandrine at pleasure among the heroick lines of ten syllables, and from him Dryden professes to have adopted it… To write verse, is to dispose syllables and sounds harmonically by some known and settled rule; a rule, however, lax enough to substitute similitude for identity, to admit change without breach of order, and to relieve the ear without disappointing it... the English heroick admits of acute or grave syllables, variously disposed. The Latin never deviates into seven feet, or exceeds the number of seventeen syllables; but the English alexandrine breaks the lawful bounds, and surprises the reader with two syllables more than he expected.[[11]]

He means by the concluding phrase that the English Alexandrine has seven feet instead of six; two syllables are either silent or lost at the pause. Catalexis and caesura in this line are not interruptions or divisions, but integral elements of the metre; intervals that either sound or silence fills. The Alexandrine becomes a catalectic Fourteener, filled up to the measure of fourteen syllables, the time of two is mute. The line, when scanned according to the caesural and final pause, has a vast liberty of catalexis; the line of seven feet being the carrying to completion of the catalectic line of six.

One may read the opening four lines of “The Muse”:

When she approaches, her immortal presence wakes me

To feel unearthly motion made upon the air

and like an aspen to reveal it: she is there,

Come, gone, elusive as the wind - thus she forsakes me. [[12]]

and observe the third line “and like an aspen to reveal it: she is there”. Reciting the whole octave, it becomes clear that this line follows its predecessor and the ear takes naturally to a one-syllable pause between “it” and “she”. Having read the subsequent line “Come, gone, elusive as the wind - thus she forsakes me”, a one-syllable pause is made before reciting it.

The line is thus transcribed:

And like/ an as/ pen to/ reveal/ it; .../ she is/ there .../

—⌣/—⌣/—⌣/—⌣/—^[[13]] /—⌣/—^

Also the line:

To feel/ unearth/ ly mo/ tion.../ made u/ pon the/ air...

—⌣/—⌣/—⌣/—^/— ⌣ /—⌣/—^

One may quote the following sentences of James Joseph Sylvester, which yet clearly state this poetic practice: “what Poe supposes to be a spondee is virtually a dactyl... the words “done? Oh!”[[14]] which he scans as a spondee, but which is really a dactyl. ‘Oh!’ being a quaver preceded by a quaver rest”.[[15]]

One may take for instance this line from “The Muse”: “Come, gone, elusive as the wind - thus she forsakes me”. The first foot “Come, gone” is an obvious dactyl, yet it reads as an iamb. The stress falls on the long sigh “gone” by prolonging the nasal sound rather than the strong consonance of “Come”; a reading that the poet, Muse-forsaken, exacts. Moreover, one may also quote the following comment of Coleridge on John Donne for further illumination: “to read Dryden, Pope, etc... you need only count syllables but to read Donne you must measure time and discover the time of each word by the sense of passion”.[[16]]

Each line is a succession of sounds and silences, each silence duly poised, each sound syllabled and vowelled. ... His were ascetic silences which were not lightly to be broken, and which he harnessed into the fervour of prayer

Again, one recalls Coleridge’s comment on Shakespeare who, “never introduces a catalectic line without intending an equivalent to the foot omitted, in the pauses, or dwelling emphasis or the diffused retardation”.[[17]] One may note this line “That I may fill mine ears with sound, mine eyes with seeing”.[[18]] Were one to consider it a six-footer, the feminine rhyme in “seeing” would be extrametrical. It is not if the line be read to the utmost of catalexis a seven-footer:

That I/ may fill/ mine ears/ with sound/ mine eyes/ with see/ ing ...

— ⌣ / — ⌣ /— ⌣/ — ⌣/ — ⌣ /— ⌣ / —^

It is silence; something more solemn than a pause, that commands this reading. A spacious room is there, stillness not to be invaded by a hasty reading until the whole length of the acatalectic Alexandrine be measured out silently to the full. It decidedly commands its time as a Fourteener with its seven accents. Thus sought Lings to make visible the bonds of verse. By variety of pauses, this measure, otherwise languorous in lyrics with its interlinear pause, becomes vital. The poet charges it with long and organic verve, capable of renewed, but not divided stimulus in mid-flight. Each line is a succession of sounds and silences, each silence duly poised, each sound syllabled and vowelled. This restraint gave form to his verse, and was not merely privative. It was sacrificial. His were ascetic silences which were not lightly to be broken, and which he harnessed into the fervour of prayer: “to pray: pause in thy fleeing”,

While I have breath; and call to me, and lead me on

Into that garden where the Muses sing and dance,

That I may fill mine ears with sound, mine eyes with seeing,

And make for men some deep enduring utterance.[[19]]

Lings must have been quick with the thought that to dictate pauses was to forbid any pauses undictated. His ear more awake to the silence of his Muse, he images her to an aspen, the tree that, most sensitive to the faintest breezes, catches the wind elusive to other treetops. This simile bears the impress of the Keatsian wit, which, despairing of all other comparisons, could only liken the cool fingers to aspen leaves.[[20]] It was their coolness of colour, little more subtly out of place and more exquisitely unlike other tree leaves in summer, which appealed to Keats. To Lings, it was the light movement of the aspen whereby it sets itself free of the motionless woods, and its liberal leaves which, like the pauses in his line, are quick with all the alertness and expectancy of the footfalls and flights of his Muse. This image has the visual as well the visional quality, being at once a simile, a metaphor and an allegory, and, in the literal sense, an image.

Lings must have reckoned, and conquered sorrow by reckoning, that his Muse could no more be constant than a breath of wind can constantly blow, that in the rhythm of his inspiration, her inconstancy is the metrical law of her arrival and departure. His numbers seems to have absconded from his own rich silences when she would take him by intimate surprise. Had he made a course of notes of her visitations, he might have been on the alert, and would have had an anticipation instead of a discovery; he might have used an Alexandrine of two halves, assertive and sure. Hence, he lets his accents occur – with full measure of time – now upon a syllable and now upon a pause within the line. He does not beseech his Muse to stay her flight, and the lines, in their metrical movement, belie the custom that she had taken leave, that the shrines of his heart are void. The lines confess, and do not suffer, the rules of inspiration: the spiritual rules of absence and presence.

a birdlike note was all about his lyric tone, quick to the ear, but long to hope and memory

Lings learnt to take his poetry as the bird takes wing, spontaneously and inevitably. His verse was not lightly given to the wind, for it, so fair a prayer in metaphor, was not intent on trying its wings, but on rising to its aim. Reticent, unobtrusive and delicate graces were his to an eminent degree. Pruned and chastened by the elect restraint of his “religion of beauty based upon art and Nature”, his early verse lived richly in the essentials of consummate form and inevitable word. In the words of Robert Browning, “Oh, the little more, and how much it is!/ And the little less, and what worlds away!”[[21]], one claims for the young Lings the little less and how much it enshrined his verse among the immortals of song, in worlds away from his own.

Hence, a birdlike note was all about his lyric tone, quick to the ear, but long to hope and memory. In his sonnet “The Birds”, he apostrophizes birds, a symbol of him, in lines winged, not weighted, with the his mystical hope that is not featherweight. He describes them as they take the summoning summer with their answering flight and song:

We sing of Summer, I the weariless cuckoo, light

And lovely of voice, and I the lark, singer and dancer

In the mid heaven, and we swallows of curved flight

That skim the meadows and the meres from dawn till night,

And we that in the gloomy woods, hidden from sight,

Ask and answer in the treetops, ask and answer.[[22]]

With liberal and educated ease, The Fourteeners and the Alexandrines wing no private thought upon intricate flight, and nothing but the birds’ weight. Nor does the poet’s thought shed an obscure hint as to betoken what suggestions of pinions had peculiar passage athwart his mind. The physics of his flight are onomatopoeic, whereby his language fulfils its primary and most elemental function. The predominant monosyllabic rhymes (“light”, “flight”, “night”...) soft and quick, convey the vital friction of the pinions. The predominant “f” sound voices the sweet music of the feather-haunted landscape.

In “The Birds”, Nature is herself, alone, and unpestered with literature. Forests are left to the birds, fells to the sunrise, streams to the wind and flowers to the bees. Over these, ranged the poet’s hope, facing day and night alone. The young poet’ instinct for the natural symbol was keen in his verse.It suffices him to see the object, with so lucent a heart’ eye, that needs not to see it more exquisitely by a similitude. Grass that seeds at the wind’s puff”,[[23]]“The sun, ripener of berries and of pods too tough”,[[24]] and “honey- gatherers in half-hidden worts and bells”,[[25]] the “weariless cuckoo, light And lovely of voice”,[[26]]“the lark, singer and dancer”[[27]], these are enough for him, such illustrious as need no illustration. Hardly an element but seems do its noble work in a rhythm correlated; hardly an element that is not an overlooked mystic. The poet even knots each element to the one before it with a simple “and” and keeps them in apostolic succession.

This quality in his early poetry is in a sense sacrificial. Its simplicity is transcendant, for which all his poetic faculties are spent and all his aesthetic riches renounced. It transcends the beauty which it implies and vouches for the riches it withholds. In these lines

And Seyis, knowing he must die,

Prayed: “O that Halcyon my wife

May know that I have lost my life,

Or she will pine amid despair

And hope, kneeling in fruitless prayer

To save from death a man long dead.

I ask that she may know instead

The certain truth, though bitter it be.

And for myself, since the wide sea

My tomb is,and since no passers-by

It can remind that here I lie—

For words on water who can grave,

Bidding men pray, my soul to save?,[[28]]

there is an easy eloquence: the simple act of language that is beyond imagery. The poet touches the inmost sense too precisely, too vitally and too delicately without the aegis of an image. This is to be insisted upon, because when Lings composed this poem, he was not aware of the sacredness of mythology. Nevertheless, his instinct for it was conspicuous. The myth in this narrative was for him profound, substantial and evocative, claiming the thought that has gone to the handling of it, the afterthought, the purpose and the deed. It was thus for him sufficient unto itself. His poetic treatment of it had a sacred finish; the vital unity rather than the inorganic polish of added thought. One cannot lay to his charge the vice whereby Corinna rebuked the young Pindar, of “sowing with the whole sack”[[29]], not with the hand. For his lyrical expression, the myth was the essence, not the adornment.

Lings composed this poem when the sea of hope for spiritual guidance ran riot in his veins, and his sails yet to be given to the waves of initiation. The story of Seyis was the imaginative leaven that lightened his solemn desire to be reinvested and reborn. Of this fact rhyming is all revealing. Lings composed the narrative in the open couplets of Keats’ Endymion. Yet unlike Keats, the running words are not vested at the mere call of rhymes. Nor are they mere stepping stones in the stream of song. In this running metre, one does not leap from rhyme to rhyme. Nor is one in danger of overlooking the subtle quality of rhyming revealed and withdrawn from one in a flash of light, on the turn of a wave. This quality is notable, for instance, in the lines in which the poet describes Iris, the winged messenger of the Queen of Heaven, who flew

[d]own to the tumult of the sea

And from his body she set free

With ease his soul, which she imbued

With Heaven’s purpose. Mid pale-hued

And luminous fish he passed, o’er stones,

Timbers from wrecks, and mortal bones,

Bedded in shifting sands, where wallow

Sea serpents, then through caverns hollow

That to their dome the ocean fills,

And rich roots of gold-hoarding hills,

Till out he came upon a deep

Thick wooded slope, and down the steep

He drifted, many fathoms more

Than lowest level of ocean floor,

To where Sleep dwells in the valley’s bed.[[30]]

Each rhyme comes down on the first syllable of the following line. The poet elaborates this effect by the use of enjambment into some sort of a metrical fugue, if one may borrow the term from the art of music to express the effect of the developing rhymes and the deferred meaning. It is “diffused retardation”,[[31]] as Coleridge describes it in Shakespeare’s blank verse, which, as the flowing wave before it subsides, takes wider and wider turns before full closure upon reaching the final full stop. Unlike Keats’ rhymes, such reduced to minimal value as to barely notice the unrhymed lines in his Endymion, the note of rhymes in “The Legend of Seyis and Halcyon” strikes the ear above all other notes and exacts urgent hearing. In this narrative, for the ear there is nothing to rest upon but rhymes. A note of return, memory, hope and ‘remembrance’ is all about them. Lings composed this poem when he had not yet reached the height of his spiritual tide. He composed it when he had a heart full of mystical hope and no sure leg to stand on. He “voyaged through strange seas of thought alone”,[[32]] and sought in his wild tide where to set his foot, as Dante wandered through Hell and Purgatory in quest of Beatrice. Rhymes in this poem of open quest, of open sea and of open couplets, far from being mere ornament, afforded in a sense the material counterpoise to the lofty spirituality of Lings’ poetic thought and his winged hope for the reassuring bonds of religion.

The “Legend of Seyis and Halcyon” harbours a thought with a close. The poet comes through the wavelike caesural enjambment at the last line, and acquiesces to the rule of Halcyons nesting upon the unruly waves, “held in reverence, for when/ They fly and swim and dance together/ About their nest, they make fair weather”.[[33]] This image is keen in the verse that by rhymes makes bargain with the tumultuous sea, and in the final testament of the poet’s conscious hope ; that his nest may be a nest of peace, and the making of peace must be in his life not the taking of arms against, but the nesting amidst its sea of troubles, the dwelling in peace enclosed by tumult.

In his poetic rehearsal of the legend, the young poet’s imagination goes beyond imagery, whither vision is simple and poetry bare. With images he was economical, and dealt least. In front of Nature and myths, he held them for a while, yet he was instinct with the rites of imagery, the delays, the pauses and the inevitability of the image for which his heart answers and his line arranges itself. He has his images in chemical solution, not in suspension.. In his sonnet the “South-Wind”, he implores the wind to

[b]low on, and let thy warm waves bountifully sweep

Upon the meadows and the woods. They tremble and quiver,

And to me hope comes that the seeds within me asleep

May know a spirit as benign as thou, a river

Of breath, and quicken, and grow upward, with roots deep,

That I may be too, in my Autumn, a rich giver.[[34]]

To seeds, fruitful at a breath of wind, the young poet imaged his mystical hope. So significant is the image of the seeds that it is at once the matter and the form; the very substance of his thought. There is no indirect similitude of “as” or “like”. He does not merely illustrate; he incarnates. This corporate image claimed his early poetry for its own; the flower yet unblossomed. His imagination was quick less with flowers and fruits than with roots and soils, more with “the seeds within me asleep”[[35]] pressing yet for life under the ground than the full-blown flower. His is the fructifierons breath of wind “in the height of heaven”[[36]] that begins on earth a “waking and a whispering”,[[37]] “invisible one,/ Bringer of storks, the cuckoo, and the swifts and swallows”,[[38]] a breath that wanders prophesizing fruition and green tides of sap that flow “as ripples run/ Over the green grass and the water of field shallows”,[[39]] a breath that would make his silence brim with all the secrets of the flower that his far-off autumn was yet to divulge .

In his sonnet “Worship”, his soul lay open to the divine as a seed-plot to the sower; “in us too He entreasured seeds of His own stuff,/ That to the light lean from their dark and narrow plot”.[[40]] To his wish for these seeds to “come to flower / In wide-eyed worship”,[[41]] an asphodel-like, “flower that death withereth not”,[[42]] the symbol of his initiation vaticinanted, which he was yet to exercise, and for many years to remain silent, pruning at leisure the potentialities of a soul, naturally quick, in the school of Sufism. That so, when he was to speak again, his utterance might be the choice fruit of the reared eye, the disciplined emotion, the purified soul and the flower of the heart, the fragrance of which withers not, but is the more delicate, because it waves in a higher air, “tall enough / To view instead of part the whole”.[[43]]

In his early poetry, the poet’s thought, ardent and serene, lay pressed unto the heart of Nature, songless in buds, with a long embrace of hope. The happy call of birth is in his poems which treat of prayer and spiritual influences; heralds of a new spirit and of somewhat vaticinal apprehension. They enclosed the hope of his spring of youth looking forward the fields of corn, and an autumn foreshadowed. They partook of “the prophetic soul/ Of the wide world dreaming on things to come”.[[44]] This fundamental chord is sounded in variety in his early poems. Hence, his concentric lyric note, and concentric evolutions of thought which he disclosed and enclosed in the round span of the sonnet. When Lings yet harboured his mystical hope behind the cloistered fences of private religion, his were words of untraveled beauty proper to their own sonnet-garden close. Sonnets proved the tabernacles wherein his imagination dwelt, the temporary dwellings of his heart wherein to rest for a time, to unburden the prompt strain and to await the answer of his prayer and the call of God.

Each sonnet of Lings’ was a prayer. It was to him the Collect in liturgy, and in its narrow compass, he found an elbowroom immeasurable for contemplation and observation. Hence, the harmony of his sonnets was an organism rather than a construction. The exertions, the intimate delays and the concerns of their creation are latent, only because they belonged to the maker and not to his verse, and because they were overcome, not merely evaded. As his instinctive conformance to the exactions of beauty in Nature and arts contained and unfolded his mystical virtues, the poet’s strict observance of the latent rules of the sonnet implied and brought its beauties hidden and subtle. Every sonnet harbours a separate and a single thought which expands and ends of itself, quickly closed, and content. The crescendo of thought, the pauses proper to octaves and sestets, Petrarchan in construction, he observed with no injury. The art of precision was contained in his use of the Italian form. One may take for instance his last sonnet “Epithalamion”:

If the god Vulcan were to come one night and stand

Beside you, lovers, grave and wise and with good will

Toward your love, and bid you ask him to fulfil

One deep wish by the cunning of his marvellous hand,

Would ye not say: These mortal bodies that were planned

So beautifully for our bliss deserve but ill

The favour of thy workmanship; for heavenly skill

Is thine, and they are of the stuff of water and sand.

But take our souls that are so large and full of light,

And while we sleep, with holy implements and flame

Weld them as thou alone hast power, till they unite

Into one essence that shall be divided never,

With wings for summits where in love it is the same

To give all, and receive all, and keep all for ever.[[45]]

The octave articulates a thought yet unfinished, which the sestet brings to a close. The dividing pause between them, as Italians intended it, is not a full pause, but a brief breathing pause at which the poet gushes out afresh to bring the octave to its fortunate ending in the sestet.

As, in music, a transposed note pines back to the keynote, for which the ear longs, so does the final period in the octave settles gently, for a recovery of breath, before the thought takes wing again. Homesick for Heaven, the poet states in the octave that mortal bodies, however beautiful, ill deserve the work of Vulcan’s refining fire. In the sestet, he resumes to beseech him to bind souls to their winged abode and enshrine divine connubiality. Another characteristic duly observed, and which betokens his strict ministration to the Italian letters, is the care he took not to close with a couplet, which otherwise would give an epigrammatic turn incongruous with the noble form of the sonnet. All his sonnets, as the present one, die soberly and collectedly away after reaching their life’s meridian in the close of the sestet with an exalted assent, “swelling loudly/Up to its climax and then dying proudly”.[[46]]

The end of the sonnet is implied in its beginning. It confesses the master passion of the poet, burningly possessed with the purgatorial desire, for a harmony that shall dissolve all his discords, and shall be divided never, and for the graces of love divine whereby he gives all, receives all and keeps all for ever. His remote dream leaves the last line of his sonnet and becomes one with Shakespeare’s: “nothing of him that doth fade/ But doth suffer a sea-change/ into something rich and strange”.[[47]]

In fourteen grandiloquent lines, Lings could not achieve grandeur. The magnitude of what his sonnets intimated, the rich silence out of which they emerged, and into which they absconded, were grander. His early poetry was of brief compass, its owner circumspect, for he had his soul to keep. His was a steadfast office of selection and exclusion. From a life of various experience, he elected what was most to his peace and from Nature and arts he elected things that suffice the eye and save the soul beside.[[48]] His choice of words further confesses this quality of rich restraint. He defines, limits and effectuates his thought not so much by assertion as by significant negatives. The particle “un” is all-distinct, all-present and all- significant in his early poetry. For instance, the epithet “unearthly”[[49]] in his sonnet “The Muse” occurred when his heavenly hope overleapt his inarticulate reserve, but as yet had not been consummated. “Unsunned”[[50]] in his sonnet “The South-Wind”; no other word so solemnly courts the sun. No word more implies so much awareness of loss, so much want of light, so much patience for absence and so much hope for retrieval, for so little stands between darkness and all the splendours of light; the little particle “un” which locks them together. Unsunned was for the time when Lings caught glimpses of Heaven, but had not as yet basked in the full joy of its light. “Unshriven”[[51]] occurs in his narrative “The Legend of Seyis and Halcyon”. It, as it were, summons in order to banish, chastises in order that it may forgive and keeps the word ‘shriven’ present to arouse remorse, confessing what was done, what is not yet done, and what shall be done.

...from 1932 onwards, he forsook verse and took to initiation. In the quiet retreat of his initiation, he indulged, for all his eager heart, in the joy of Halcyons, nesting on the vast sea of Sufism

His were meanings assembled yet unforced, fastened yet not mingled, and distinct yet undivided, in his negation of all that is flawed, and his positive hope thence derived. The perfection of his vision was too great for prodigal words, only the narrow lyric course, a quatrain and a sestet could suffice. His was the medieval mystic Muhammad Al Niffari’s thought, in a sense more subtle than the statement was meant to contain, that the “wider the vision, the narrower the phrase”.[[52]] To cast up his accounts with God was what he sought, not with loud verse, but with a soul wrapt with such fire as anointed Isaiah lips. Thus sealed his lips were to be for nearly twenty years of spiritual labour. To consummation rose his mystical hope like the temple of Solomon, with no sound of axe or hammer, and in sacred silence he kept his highmost song.

Later poetry

…reading the later poems evokes pent-up floodwater at last released by the blasting of a dam

The young poet of the renounced lyre sacrificed his passion for poetry only, as the word ‘sacrifice’ means etymologically, to sanctify it; ‘sacrum-facere’. The young poet of heavenly fealties reckoned that the hour had come for silence when, from 1932 onwards, he forsook verse and took to initiation. In the quiet retreat of his initiation, he indulged, for all his eager heart, in the joy of Halcyons, nesting on the vast sea of Sufism, and forewent all that waved him away from the consummation of a long-nursed hope.

After a surcease of two decades, he gave himself back to the Muse he served wisely in the years of youth. It is nothing less than remarkable to note that he spoke with the same spiritual accent from early to late maturity. His poems, though more wrought and complex are the later, are of a piece, beautiful and organic in their coherence. His life was a song of praise, of strains twofold. Ever present was either, yet the later strain was all-commanding, all earnest and all-sustained.

Strain implies stress; but likewise implies song; and it is was upon a strained cord that Lings’ later song rested. It was a consequence, artistic and spiritual, long envisaged. His style, so inevitable and natural, was not unrehearsed or unstudied. Lings had been, prior to the resumption of his poetic labours, laying the foundation for the fresh exercise of his Muse by the study of alliteration. Hand in hand his spiritual experience and artistic maturity trod the winepress of his poetry until the vintage is attained in his later poems. Hence, his poetry confessed a spiritual growth rather than any temperamental or stylistic rupture. The Heaven-tongued instinct of the young poet’s heart, long inarticulate, has found at length fit utterance and, approved by metaphysical knowledge, gained what of old it wanted. The early instincts, losing nothing of their spring and ineffability, now ripened, speak ex cathedra, in the success of life, in the success of thought and in the success of form. It is not without cause that reading the later poems evokes pent-up floodwater at last released by the blasting of a dam. It is not without cause that their characteristic note is stress.

Richness is the quality so distinctive of Lings’ later verse. His early poetry is the apple-blossom, delicate and fragrant; the later poetry the apple, fragrant and rich. His development was a process. In his early verse, he was scrupulous to the mint, anise and cumin of his art. In his later, he proved himself a possessor of the weightier matters of the law of spirit and art; the law that he so fulfilled with a liberty of perfection that it had become a spontaneous habit. The rhythm of his verse was the reverberation of the inward music that his spirit breathed: the Poet-Sufi law unto himself. No more guidance he needed from formal rule; having a finer rule within him. He moved from the trained subtlety of his earlier verse to the liberal grace of the later.

Alliteration claimed the poet’s verse in his mature song. “This alliterative metre, with its frequent clash of stressed syllables, I have used for all my later poems which are, as regards their form, the fruit of my apprenticeship to it in those early years”.[[53]] Not the formless alliteration, observed by no rule of stress, which grew manifest in English verse when metres ordered by rhyme[[54]] superseded the alliterative metre, nor Alexander Pope’s “alliteration’s artful aid” was Lings’. Rather the metre of his verse and not its adjunct, its meat and not its seasoning his alliteration was. In accordance with its ancient tradition, it depends on “four heavily stressed syllables in each line, and one or both of the first two of these stresses must alliterate with the third, that is, they must begin with the same consonantal sound, whether it is actually spelled with the same letter or not. Two stresses often clash together... This syncopation has remained one of the most outstanding phonetic features of our language as normally spoken, and the alliterative metre does full justice to it, giving ample scope for the keen resonance which can result from the collision of two heavily weighted syllables, neither of which will yield to the other. That constantly recurrent effect, together with the ever-varying quantity of light syllables, is what contributes more than anything else to the wide rhythmic difference between our most indigenous form of verse and those iambic metres which ousted it from English poetry towards the end of the Middle Ages.”[[55]]

Unlike conventional rhythm, the Anglo-Saxon verse lived on the stress of natural speech rhythms, and took speech units of stress as it determining law. Free from syllabic enumeration, it hinges not on the metrical form to produce a stress alien to the natural speech. The alliterative verse cannot dictate the stress for the simple reason that the very stress makes the verse and braces its skeleton. It needs be read for its very sense, with its natural pauses and without thinking of syllables. Hence, its winged ease. It “needs exactly the same intonation as that of normal speech... All that is in fact necessary is to read the lines naturally, according to the senses. There is no need for the reader to analyse them metrically”.[[56]] For instance, one should not read Lings’ line “It is not nothing to have known the love”[[57]] as a line of blank verse, but rather suchwise, according to the sense stress: “It is nót nóthing to have knówn the love”. Though the essence of the line is the rising rhythm, with its main accents on the second syllables, the beauty of Lings’ line consists in the dislocation or variance of those accents.

Lings disinterred a tradition in English poetry that was richer than the one in possession in his own day. Not that it was the earliest and most ancient rhythm of English verse; this would be a fact of no worth in itself, but it was a rhythm still inherent in the English language, and only held in check by an artificial convention. The law of the alliterative rhythm, the primitive pattern of song out of which verse evolved, is subtle. Lings absorbed this poetic law not only from his practiced prime of age, but from absorbing within himself the Sufi law. When he received unto himself the Divine Law, the spiritual magnetization whereby his soul pointed infallibly towards God, he needed no longer to seek guidance from the compass of formal rules. He had cast off all visible fetters, but had not escaped into insignificant liberty. If he be a law unto himself, he was so only by a simple obligation to a larger law to which he had appealed in spirit and letters. His poetic flight thus overruled the bridle of syllabic units and found in the natural rhythm of stress its winged horse. Alliteration, so to say, obeyed the unwritten laws of his spirit.

For not by an over close cultivation did he ‘make’ his work beautiful. He rather beautified himself.

In his earliest moments when he was not yet marching in his Sufi wool the march of his alternative verse, but pacing softly in the strictest measures of the bonds that all true poets so love, the bonds of stress, quantity, numbers, rhymes and movement, the delicate beauty of his sonnets proved his delight in that order and in those his diction was inconspicuous. His later diction found in the strain of alliteration its largest liberty and capacities, for such rhythm far more exacts the command of language than measured verse. Words need be more beautiful in themselves, for they no more acquire any adventitious charm from mechanical devices. For not by an over close cultivation did he ‘make’ his work beautiful. He rather beautified himself.

The vital friction of his early verse was the friction of the pinion to the air. For its metrical flight, he elected the bird, wild and liberal, with two equal pinions that beat in expected measure. His later verse acquired through its alliterative metre a note of surprise, a rhythmic bird caught in the breaths of wind. Once the captive tunes are liberated, the poet-Sufi concerns himself less as to their flight. For he now knows that there are magnetic airflows in the common air, spirited breaths of wind that blow infallibly, and in their highmost currents the wings of his later song are governed, as the carrier doves to their decided destination. When, at the summons of an emancipating inspiration, he trod upon air immense, mystical and rare, he could afford to be heedless of his footprints.

The fresh initiate earned his soul, and was proud of the possession, which he sought to express in poetical words. His later verse was hence broad-pinioned and, though Lings rendered variations more studious upon it, more refinedly simple than his earlier. One may compare his description of the South wind in early eponymous poem; “A breath: and in the height of Heaven leisurely follows/ Cloud upon cloud, and on the earth there has began/ A waking and a whispering...”,[[58]] with his other description of it in his later poem “Spring-Summer”; “The sound of the woods sighing at the passage/ Of the South-West wind is a wave that breaks/ Gently, joyously, jubilantly into birdsong”.[[59]] The first-quoted lines are inversions impossible to render in natural speech. They are read according to the iambic rule. In the second-quoted lines, the very natural-speech emphasis yields the rhythm, for the stresses of alliteration are determined simply by the language and its sense. Each metrical movement is fine on its own way. Yet the later poems have in unrivalled degree the right ease, the authentic beauty and the uncoerced expressiveness.

However the early Lings wrote with a full sense of accent and with full measure of time, his later verse rings most true. His endeavour was assuredly towards a freer form of verse, but aimed only towards the normal stress and pause in English language and is, therefore, as rigorously bound by law as metre can be when it ceases to be entirely ruled by the expectancy of rhythm. His recourse to a freer form of expression was for him of immeasurable advantage. It permitted him to abandon himself, without his earlier reserve, to the rapture of poetry, which in him was of the same nature as philosophy, without the need to transpose his high strains to lower keys. It allowed him a choice, formal yet supple way of expression for his uninterrupted meditation on divine secrets.

Lings’ metrical emancipation is all the more commensurate with the distinct note of his later verse, which seeks to liberate rather than capture those secrets. The poet-Sufi conceived of his task not as a “capturing” of the Presence but rather as a ‘liberation’ of its mysterious Totality from the deceptive prison of appearances. “Islam is particularly averse to any idea of circumscribing or localizing the Divine, or limiting it in any way”.[[60]] He does not bring the reader into swift possession of a fugitive beauty departed of its reserve, but liberates it, glimpse-wise, to be his sure possession; “unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance”.[[61]] There is a call from his later verse to the reader, with resounding summons, to “never bid farewell to beauty, never take,/ Leave of delight, but wave it welcome: it is thine”,[[62]] to “go to meet her; set forth now, this day, this hour”.[[63]] A call, none the less, to which not in every one’s capacity - uneducated to the exactions of such beauty - is to cry: Adsum!

Lings’ later music was but the outward development of the harmony within. … their metre is the very breath of life.

It is in order to consider the phases of the initiatic process, from which Lings’ poetic development derives a certain justification. The first phase is when the soul experiences contraction or qabd, that is, ascetic rigour, detachment from the world and sober discipline through manifestation (tajalli) of divine majesty. The second phase is when the soul undergoes expansion or bast, a growth that involves the manifestation of divine beauty. Music is proper to the second phase. That is, the Islamic law, or sharia, tends to prohibit listening to music unless it be in its immaculate form, that is, the recitation of the Qur'anic verses. Sufism, concerned with the esoteric path, sanctions music, which in some Sufi orders even possesses significant importance. Modern musical habits, however, make for expansion or elation without entering upon the first phase. Hence, bringing the soul to a state of elation unbegotten of spiritual alchemy.

Sufis, keenly alive to this fact, have permitted music and spiritual concert (samaa) only for ones who have passed through the initial phase in the sanctification of the soul.[[64]]

“The purely religious use of music and dancing: such is that of who by this means stir up in themselves greater love towards God, and, by means of music, often obtain spiritual visions and ecstasies, their heart becoming in this condition as clean as silver in the flame of a furnace, and attaining a degree of purity which could never be attained by any amount of mere outward austerities... The disciple, however, whose heart is not thoroughly purged from earthly desires, though he may have obtained some glimpse of the Mystics’ path, should be forbidden by his director to take part in such dances, as they will do him more harm than good.”[[65]]

Indulgence in music without fulfilling the initial phase of the mystical path withholds the immeasurable expanse of the superior realm. If the soul, failing the fundamental sanction, takes wing to that realm for few moments by the aid of music, it will forthwith fall down, prostrate with its inability to maintain the spiritual state of expansion when the music ceases. In view of these facts, Lings’ later music was but the outward development of the harmony within. Its length, its height, its liberty, its expansion and its sustained rapture are organically coherent with the first circumspect, contracted, portion of his poetry; the flower in art of his initiation fully suffered. Now with leave to safely look within and sing, he announced, as the traveller greets sunrise in the ultimate summit, “slowly, imperceptibly, surely, inexorably”,[[66]] his soul’s emancipation in the remoter liberty of the old alliterative metre and its ‘interior’ law.

Lings thus asserted the mintmark of his poetry, of youth as of age. His metrical development was spiritually significant. Yet he might have all the more affirmed, seeing what he thought of the vitality of metre, that his knowledge, speaking forthwith in the long breath of alliterative verse, was an emancipated entreprise, liberated at a great price. Although the governed lines of his early sonnets were to him wings, not fetters, his later poems flew yet on a weightier and loftier pinion. Their flight was into sidereal realms. They went, through the essentially private human heart, furthermost into the Garden of the Heart. Hence, the early lyric note gave way to another charged more with thoughts that exact a larger utterance and a weightier music. There is neither octave nor sestet in his stanzaic later poems, because their metre is the very breath of life. The awe of the heart and the breath of rapture are the law of the poet’s lines. His poems leapt the fences of the sonnet’s garden, and walked, not astray, into the remoter liberty where all is interior law. Seldom is a stanzaic poem so complete but that other stanzas might have been added; but Lings’ has the unity of life, and when each poem ends, it does so for ever and ever.

No addendum there is in the poet’s emotion in the later poetry, but only the earliest approved, sanctioned and crystallized. Silent pauses damasked his earlier lines, wherein he caught and detained the winged Muse by nothing, so to speak, more forceful than a fingertip. One may liken their ease to the loosening of the caged notes in a bird’s throat; nothing forced or in the expression of the mystical hope to spend and be spent in divine love. The note was soft-toned, promiser of a rapture ineffable. The Kingdom of Heaven suffereth violence, but as the young poet did none, the Kingdom of Heaven yielded to his delight.

The poet’s hope unloosed at length from the cage of words, chorister at the altar of beauty, the sharp note of the cock’s crowing is now at his tongue’s end. Thus, in the opening lines of the first of his later poems, “The Garden”, the poet measures the memory span of one’s mental ear and puts the second and third alliterative word where the memory of the first is just beginning to soften, and has not quite waned:

The cock’s crowing cleaves my breast,

Opens me to the eloquence of the eloquent doves.

Their clear cadences bring coolness to my heart -

Mercifullest of the merciful, have mercy upon us![[67]]

He composed it just after his spiritual retreat. “The Garden of its theme is in Egypt, and the line that serves as refrain is the translation of an Islamic prayer”.[[68]] The traces of the East were vital to his later poetry. There it flowered, and like the Eastern for whom sunshine is all-sufficing, he had in it but the richness of Virgin Nature.

His verse he gives to Nature unreservedly, with the magnanimity of the gifts of love, pure because his own self is unremembered.

In this poem, close to Nature is the poet’s ear, and to her rich voices, which he simply alliterates as he hears them. In these lines, gentle and close, various odours throng each other, and fruits and herbs are in full eruption:

...here luminous in the shade

Glowing like garnets, globes and chalices.

And stars: saffron, sapphire and ivory,

Ochre and amethyst, with eyes of jet;

And to the sun’s splendour splendour offering,

Fragrant lilies, celestially white.[[69]]

The poet’s senses resound praises of Nature, so alert to the the summons of her sacred symbols that he holds at heart the wild honour of every element described. Nor does his description lack the ascetic guard of honour: the austerity of the poet’s mind around whom arrayed are the beauties of Nature, quiet as a Sufi breathless with adoration, the note of reserve which was the inmate of his young poetic heart and which he learned to name “ a pious courtesy related to awe and to the artist's consciousness of the Divine Majesty”.[[70]] His verse he gives to Nature unreservedly, with the magnanimity of the gifts of love, pure because his own self is unremembered. Her language is articulate and eloquent, unmarred with added notes of his. Such eager to hear her music as would not lose any tone of it by making too much noise himself, he highlights it with sense-stress.

The fire of the poet’s anvil is all lighted from sunshine, with a golden hair-breadth of alliterative precision. Sunlight is the loud rapture of his lines and waters. Waters speak but to offer further felicity:

Eloquent, eloquent, eloquent the waters,

Flowing fountains that fall upon the stones,

Unruffled pools, serene and deep,

Swept by the swallows, the swan’s paradise

To cruise quietly over the calm surface.[[71]]

Blessedness is for him to hearken to her music, quickener of his fine impulse:

Eloquent the evening, the airs stillness,

The vast silences that swell up from the earth,

And fall, floating, as on flowers the dew,

Messengers of Purity, remembrances of Peace.

High and Holy, Hearer of their orison.[[72]]

Alliteration keeps his versification delicately multitudinous and reverberates what it sings with the happy trammels of stress. For, Nature has something more solemn than manifold variety; she has manifold singleness.

Although Lings was intent on marking graphically the metrical stress because “for English readers, there is no problem here except the unaccustomed absence of a problem whose presence has become almost second nature to them: they have to remember to retain the intonation of normal speech and not to make the subtle compromise which the rhythm of most English poetry demands, and which they will need for the other poems in this volume”,[[73]] he was all the more grasping at a stress that goes beyond the visual realm to meet the fresh perils of speech-rhythms. He beckoned the reader take the line as a line of prose, perhaps only with that delicate vibration in the voice, which confesses the fine and grave words of poetry. He beckoned him hear the alliterative sounds without the visual aid of consonants and vowels marked. That he hoped to rely on the reader’s ear implies that this primeval rhythm, upon which the evolution of verse and the elaboration of metrical movements depended, is what all ears are naturally predisposed to apprehend. He did not force the note lest it should cease to stir an echo in the human heart. Inalienable, spontaneous and inevitable was his later poetical art. Of it scarce nothing fitter could be said than is expressed in the lines of Shakespeare in The Winter's Tale; “This is an art/ Which does mend nature, change it rather, but/ The art itself is nature”.[[74]]

The manifestation of Divine beauty is the minted glory of Lings’s later verse. Manifestations, repetitional and perennial, is the word more proper. His alliteration enshrines this theme, a recurrence of it, a rhyme, so to say, not of sound but of idea; variation of a certain kind that goes beyond the realm of music. His alliteration not only meets the language of his heart’s content, which cannot articulate at once all the gratitude. It also rehearses the design of Divine manifestation; the manifestation of the One in more forms than one. Elements as appointed ministers vouchsafing him yonder glimpses through a glass darkly, his senses rightly possessed of what they are made for, his heart set athrob for the Infinite; these the poet sings in the repetitions of Nature; the procession and recessions of her seasons.

He rehearses in his description of seasons the metaphysical themes of meditation.

The vintage Lings is not simple except with the simplicity that a poet must have who thus separates his poems: The Garden, Spring-Summer, Midsummer, Autumn, The Elements, The Heralds… He rehearses in his description of seasons the metaphysical themes of meditation. In his mudhakara, Schuon’s teachings upon his initiation into Sufism, he states “that those themes are means of conforming to the divine presence and the reason why we conform to the divine presence by using the themes is that Allah Ta‘alah has made the themes a part of man’s nature. When He created man, He created with man these different modes, these different spiritual attitudes; attitudes towards himself. They are part of man’s primordial nature. These themes of meditations are not things we have to acquire. They are already in our nature. They are deep in our nature... These themes, the first four themes are the dimensions of the primordial soul. They correspond in the little world of the soul to the directions of space in the big outer world.”

The first theme is the cold theme, and corresponds to winter. “The Shaykh uses the word abstention as the key word to this theme”. It denotes purity, renunciation, sacrifice and fear of God. The second theme corresponds to spring, and denotes vigilance, initiative and regeneration. The third theme corresponds to autumn, and implies serenity and peace. The fourth theme corresponds to summer; the season of warmth, love and giving oneself to God.

The poet-Sufi patterns the evolution of the soul upon the different seasons. Predominant are summer and autumn in his later verse, with little of spring and of winter none. Thus he sings of midsummer as

Trespass of Eternity upon time’s empire,

Serene respite from the running of the hours,

Mark our memories with remembrance of this day,

With its sights and sounds our senses imbue.

Print imperishably its repose upon our hearts,

That when whirled onwards on the wheel of the months

Undimmed we may retain this treasure within us,

Our midsummer of the soul, our mirror of Peace.[[75]]

The theme of winter is a theme of contraction ‘Qabd’, whilst the themes of autumn and summer are themes of expansion ‘Bast’; spring being a rite of passage, “the Holy War” that belongs outright to neither. Thus he sings of the singular secret of spring, which is

to plunder as the bees plunder the flowers,

Entering into its inmost cup

To drink deeply, dwelling in its fragrance,

To sanctify our souls with the certainty of Heaven.

(“Spring-Summer”, 36-9)[[76]]

Thus he sings of summer:

Let thought stand still: the solstice, the year’s noon,

Is Summer without Spring, Summer without Autumn.[[77]]

And thus he sings of autumn:

Spent is the outward urge, the forethrust

Of branches; in retreat are the trees, benign

Yet aloof, gently majestic, withdrawn

Each one into itself, for their Summer’s wave

Ebbs, and their sanctuary is inwardness and depth.[[78]]

Either category, ‘bast’ and ‘qabd’, adumbrates Sufi orders. A Sufi way, in which the predominant discipline is contraction, is called ‘majestic’ or ‘Tariqah Jalaliyyah’, for its training displays the divine attributes of majesty and severity. It consists of purging the soul to behold at length the Divine Presence. A Sufi way, in which the predominant discipline is expansion, is called ‘beauteous’, or ‘Tariqah Jamaliyyah’, for its training displays the divine attributes of beauty and mercy. It initiates the disciple to the Divine Presence by invoking the Supreme Name ‘Allah’, to be granted, less through spiritual austerities than gratitude, direct knowledge in virtue of which he purges his heart. The Maryamiyyah Sufi order, into which Lings was initiated, was a branch of the Alawiyah Sufi order, styled after the Shadhili order, being itself a beauteous order, or ‘Tariqah Jamaliyyah’, which trains the disciple rather by love, invocation and gratitude than spiritual struggle.

A mystic born, not made, nurture availed much to the young Lings, and was as serviceable to him as of his own election, but nature availed him more. Not a worshipper with loins girt, he was rather predestined to a beauteous path of sanctity. For, Heaven not only attested her primacy in him by birthright, but owned him by gentle, not fierce, confession. His was a gentle development, and to no exertion he girded his will. The course of his initiation was not a wintertide office. It ran smooth; its evolutions were rather the ripples of a “sweet April shower”[[79]] which passed him lightly by, than the waves of a winter storm. In the wind-chart of his soul, the first wind that blew was from the south. His was the spring and the summer in the calendar of the Spirit. Thus he dwells, neither with omission nor with commission, but beauteously upon the holy beauties of Nature, suffering her spiritual laws, which implies the limitation of the ‘beauteous way’, offering strength to the strong; to him that hath it gives more”.[[80]] It is an elect limitation, yet it is never an elected strain save by the very few, and Lings has made it quite his own. Upon it, in his poetry, one must needs dwell studiously, often in a spirit of prayer.

Lings’ spirituality was the accent of his verse, the idiom of his thought and the measure of his emotion. The objective of the foregoing has been to study Lings the poet in his closet, in the light of his spiritual experience which summoned his juvenile poetic buds to their noble flowering. The full-blown post-initiation poems display, rather than, as do the early poems, betray the qualities of his poetic art and the features of his mysticism. He entrusted the range and flight of his thought and the urgency of his emotion in his earlier poetry to the custody of the explicit form of sonnets, Alexandrines, Fourteeners and tetrameters; the law of common consent, and in his later verse to the less obvious, yet equally definite and implicit form of old alliteration, the Sufi’s law unto himself.

The metrical development confesses every change through which Lings had passed in his spiritual life. In his survey and formal analysis of Sufi poetry in the Abbasid period, published in The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: Abbasid Belles-Lettres, Lings wrote that “the poetry of the mystics reveals certain aspects of their spirituality more than any other source is capable of doing”.[[81]] And, bequeathing his poems for posterity, to be approached from the side of poetry must have been the conscious hope of Martin Lings, “poet and saint”,[[82]] so sang Abraham Cowley of his friend Richard Crashaw, “the hard and rarest union which can be”.

Works Cited

Lings, Martin. Collected Poems. Cambridge: Archetype, 2002.

Lings, Lings. Splendours of Qur’an Calligraphy and Illumination. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005.

Keats, John. Selected Poems and Letters of Keats, ed. Robert Gittings. London: Heinemann, 1976.

Keats, John. Poems 1817. Oxford : Woodstock Books, 1989.

Johnson, Samuel. The Lives of the English Poets. London: Jones&Co., 1825.

Sylvester, James J. The Laws of Verse: Or Principles of Versification Exemplified in Metrical Translations. London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1870.

Donne, John. The Critical Heritage, vol II, ed. A.J Smith and Catherine Philips. London: Routledge, 1996.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Coleridge's Essays & Lectures on Shakespeare & Some Other Old Poets & Dramatists, ed. J.M Dent. London: J.M Dent and Sons, 1907.

Browning, Robert. The Complete Poetical Works of Robert Browning, ed. Horace E. Scudder. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1895.

Plutarch. Plutarch's Essays and Miscellanies, Comprising All the Works Collected under the Title of “Morals”, ed. Arthur Hugh Clough, William Watson Goodwin. Iowa: Little, Brown, and Company, 1878.

Wordsworth, William. The complete poetical works of William Wordsworth, Ed. William Knight. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904.

Shakespeare, William. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, ed. W.J Craig. Oxford University Press, 1914.

Arberry A.J. The Mawāqif and Mukhāt ̣ abāt of Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Jabbār al-Niffarī. Gibb Memorial Trust, 1935.Daniels, Samuel. Poems, and A Defense of Rhyme, ed. Arthur Colby Sprague. The University of Chicago Press, 1965.

Al-Ghazzali. The Alchemy of Happiness, ed. Claud Field. London: J. Murray, 1910.

Tusser, Thomas. Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry. London: Lackington, Allen, and Company, 1812.

The Cambridge History Of Arabic Literature: Abbasid Belles-Lettres. Ed. Julia Ashtiany, T. M. Johnstone, J. D. Latham, R. B. Serjeant and G. Rex Smith. Cambridge University Press. 1990.

Cowley, Abraham. The Works of Mr. Abraham Cowley, ed. Thomas Sprat. London: J.M for H. Herringman, 1678.

[[1]]: Martin Lings, “Spring-Summer”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 28, lines 7-13

[[2]]: Martin Lings, “The South Wind”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 18, lines 3-4

[[3]]: The Welsh term for white is Gwyn. It denotes holiness, felicity, fairness and reverence; much in the sense of Robert Herrick’s “White Island, or Place of the Blest”

[[4]]: As Marius in Les Mésirables describes a woman that walks in light to her lover’s vision : “Le jour où une femme passe devant vous dégage de la lumière en marchant, vous êtes perdus, vous aimez”

[[5]]: Martin Lings, “Preface”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 9

[[6]]: Martin Lings, “The Muse”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 13, line 1

[[7]]: John Keats, “On first looking into Chapman’s Homer”, in Selected Poems and Letters of Keats, ed. Robert Gittings (London: Heinemann, 1976), 25, lines 9-10

[[8]]: Martin Lings, “The Muse”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 13, line 2

[[9]]: John Dryden kept the French measure with its middle caesura. Abraham Cowley’s use of Alexandrines in his Pindaric Odes differs in keeping the line of six feet with no break midway, that is, a full line of twelve syllables, not a line of two halves. For instance, one may clearly note the difference between Cowley’s line from his ode “The Muse”: “To fill up half the orb of Round Eternity” (IV-17) , and Dryden’s line from his “Lucretius” “But run the round again, the round I ran before” (III-140)

[[10]]: Samuel Johnson, The Lives of the English Poets. (London: Jones & Co., 1825), 20

[[11]]: Samuel Johnson, The Lives of the English Poets. (London: Jones & Co., 1825), 129

[[12]]: Martin Lings, “The Muse”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 13, lines 1-4

[[13]]: ^ is a symbol of silence

[[14]]: Reference to the lines (17-18) from Lord Byron’s poem “The Bride of Abydos”: “Can he smile on such deeds as his children have done?/ Oh! wild as the accents of lovers' farewell”

[[15]]: James Joseph Sylvester. The Laws of Verse: Or Principles of Versification Exemplified in Metrical Translations. (London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1870), 68

[[16]]: John Donne. The Critical Heritage, vol II, ed. A.J Smith and Catherine Philips. (London: Routledge, 1996), 75

[[17]]: Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge's Essays & Lectures on Shakespeare & Some Other Old Poets & Dramatists, ed. J.M Dent. (London: J.M Dent and Sons, 1907), 164

[[18]]: Martin Lings, “The Muse”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 13, line 13

[[19]]: Martin Lings, “The Muse”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 13, lines 10-4

[[20]]: The line in John Keats Endymion, Book II, line 520: “With fingers cool as aspen leaves”

[[21]]: Robert Browning, “By The Fire-Side”, The Complete Poetical Works of Robert Browning, ed. Horace E. Scudder (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1895), 187, line 191

[[22]]: Martin Lings, “The Birds”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 19, lines 9-14

[[23]]: Line 3

[[24]]: Line 6

[[25]]: Line 4

[[26]]: Lines 9-10

[[27]]: Line 10

[[28]]: Martin Lings, “The Legend of Seyis and Halcyon”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 14, lines 10-22

[[29]]: Plutarch. Plutarch's Essays and Miscellanies, Comprising All the Works Collected under the Title of “Morals”, ed. Arthur Hugh Clough, William Watson Goodwin. (Iowa: Little, Brown, and Company, 1878), 404. The excerpt is taken from this passage:

“Corinna likewise, when Pindar was but a young man and made too daring a use of his eloquence, gave him this admonition, that he was no poet, for that he never composed any fables, which was the chiefest office of poetry; in regard that strange words, figures, metaphors, songs, and measures were invented to give a sweetness to things... : When you sow, you must scatter the seed with your hand, not empty the whole sack at once..”

[[30]]: Martin Lings, “The Legend of Seyis and Halcyon”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 14-5, lines 31-45

[[31]]: Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge's Essays & Lectures on Shakespeare & Some Other Old Poets & Dramatists, ed. J.M Dent. (London: J.M Dent and Sons, 1907), 145

[[32]]: William Wordsworth. “The Prelude”, Book III. The complete poetical works of William Wordsworth, Ed. William Knight. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), 139, lines 74-5

[[33]]: Martin Lings, “The Legend of Seyis and Halcyon”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 17, lines 120-2

[[34]]: Martin Lings, “The South Wind”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 18, lines 9-14

[[35]]: Line 11

[[36]]: Line 1

[[37]]: Line 3

[[38]]: Lines 7-8

[[39]]: Lines 3-4

[[40]]: Martin Lings, “Worship”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 21, lines 9-10

[[41]]: Lines 13-4

[[42]]: Lines 14

[[43]]: Line 12-3

[[44]]: William Shakespeare, “Sonnet 107”. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, ed. W.J Craig. (Oxford University Press, 1914), 1308, lines 1-2

[[45]]: Martin Lings, “Epithalamion”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 20, lines 1-14

[[46]]: John Keats. “To Charles Cowden Clarke” John Keats: Poems 1817. (Oxford : Woodstock Books, 1989). 71, lines 59-60

[[47]]: William Shakespeare, “The Tempest”. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, ed. W.J Craig. (Oxford University Press, 1914), 6, lines 397-8

[[48]]: Robert Browning, “The Book and the Ring”, The Book and the Ring, vol I, ed. Charlotte Porter and Helen A.Clarke. book XII, line 863

[[49]]: Martin Lings, “The Muse”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 13, line 2

[[50]]: Martin Lings, “The South-Wind”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 18, line 5

[[51]]: Martin Lings, “The Legend of Seyis and Halcyon”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 14, line 23

[[52]]: A. J. Arberry, The Mawāqif and Mukhāt ̣ abāt of Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Jabbār al-Niffarī. (Gibb Memorial Trust, 1935), 117. “When He widened my vision, He narrowed my phrase”. (Arberry’s rendering)

[[53]]: Martin Lings, The Elements and Other Poems. (London: Perennial Books, 1967), 3

[[54]]: It is worthwhile to note that Lings forsook not in his later verse the use of rhymes, although rhyming was not used in the old alliterative metre. The stress of words in his alliterative lines so naturally calls for rhymes that he seemed to fulfill the thought of Samuel Daniel in his A Defense of Rhyme; that “in an eminent spirit, whom Nature hath fitted for that mystery, Rhyme is no impediment to his conceit, but rather gives him wings to mount, and carries him not out of his course, but as it were beyond his power to a far happier flight”. In the later poems, he bids one ascend the mountain heights. Although they treat of loftier and stricter themes, he never fails to recall one to the gentler fences of his youth. Samuel Daniels, Poems, and A Defense of Rhyme, ed. Arthur Colby Sprague. (The University of Chicago Press, 1965), 27

[[55]]: Martin Lings, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 25

[[56]]: Martin Lings, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 25

[[57]]: Martin Lings, “The Elements”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 34, line 20

[[58]]: Martin Lings, “The South-Wind”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 18, lines 1-3

[[59]]: Martin Lings, “Spring-Summer”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 28, lines 1-3

[[60]]: Martin, Lings. Splendours of Qur’an Calligraphy and Illumination, (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005), 15

[[61]]: Matthew, 25:26

[[62]]: Martin Lings, “The Heralds”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 40, lines 1-2

[[63]]: Martin Lings, “The Heralds”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 41, line 39

[[64]]: In this context, it is in order to note that the banishment of arts from the Platonic polity was not because he condemned them, but because he dreaded lest the citizens should love them too well

[[65]]: Al-Ghazzali. “Chapter V: Concerning Music and Dancing as Aids to the Religious Life”. The Alchemy of Happiness, ed. Claud Field. (London: J. Murray, 1910), 26-7

[[66]]: Martin Lings, “Autumn”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), “32, lines 21

[[67]]: Martin Lings, “The Garden”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 26, lines 1-2

[[68]]: Martin Lings, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 10

[[69]]: Martin Lings, “The Garden”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 26, lines 11-6

[[70]]: Martin, Lings. Splendours of Qur’an Calligraphy and Illumination, (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005), 20

[[71]]: Martin Lings, “The Garden”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 26-7, lines 20-6

[[72]]: Martin Lings, “The Garden”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 27, lines 35-9

[[73]]: Martin Lings, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 25

[[74]]: William Shakespeare, “The Winter’s Tale”. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, ed. W.J.Craig. (Oxford University Press, 1914), 341, lines 95-6

[[75]]: Martin Lings, “Midsummer”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 31, lines 58-65

[[76]]: Martin Lings, “Spring-Summer”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 29, lines 36-9

[[77]]: Martin Lings, “Midsummer”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 30, lines 4-5

[[78]]: Martin Lings, “Autumn”, Collected Poems (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), 32, lines 38-42

[[79]]: Thomas, Tusser. “April’s Husbandry”. Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry (London: Lackington, Allen, and Company, 1812), 135

[[80]]: Matthew, 25:29

[[81]]: The Cambridge History Of Arabic Literature: Abbasid Belles-Lettres. Ed. Julia Ashtiany, T. M. Johnstone, J. D. Latham, R. B. Serjeant and G. Rex Smith. (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 264

[[82]]: Abraham Cowley, “On The Death Of Mr.Crashaw”. The Works of Mr. Abraham Cowley, ed. Thomas Sprat. (London: J.M for H. Herringman, 1678), 29, lines 1-3