We are on a journey through the inward space of the heart, a journey not measured by the hours of our watch or the days of the calendar, for it is a journey out of time into eternity.[[1]][[2]]

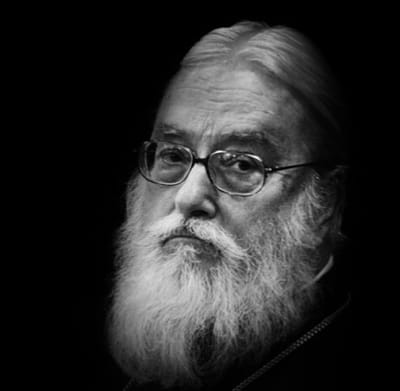

Timothy Ware was born in Bath in 1934 and raised in an evangelical Anglican family. At sixteen he discovered Helen Waddell’s marvellous book on the Desert Fathers which he found ‘instantly attractive’.[[3]] Soon after he found himself inside a Russian Orthodox Church (St Philip’s in central London, since demolished) during the vigil service on a Saturday evening. Here too, despite the fact that the liturgy was conducted in an unknown language, he found ‘an immediate attraction’ and was overwhelmed by the sense that the church was full of ‘invisible worshippers’:

I felt a sense of the unity between our earthly worship and the worship in Heaven. I had a vivid sense of the living reality of the communion of saints. I didn’t understand anything that was said, because it was all in Slavonic. But, again … I felt an immediate attraction. … I waited six years before joining the Orthodox Church. I wouldn’t say my mind was made up on that Saturday afternoon. But that experience gave a direction to my life, which meant I felt more and more that my ‘true home’ was in the Orthodox Church.[[4]]

Some years later he was reminded, with ‘a shock of recognition’, of his experience in St Philip’s when reading an account of St Vladimir’s attendance at the Divine Liturgy in Constantinople; he and his friends ‘knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendour or beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it. We only know that God dwells among men’.[[5]]

Amongst the attractions of Orthodoxy was the sense of a uninterrupted living tradition:

When I began to read about Orthodoxy, I was impressed by a sense of living tradition. I felt, ‘Here is a church with deep roots in the past; a church that has not undergone the Scholasticism of the West and the Middle Ages, nor the fraction and breaking that took place with the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, and that has not been profoundly influenced by the Enlightenment; a church that remains the church of the early martyrs of confessors, the church of the early fathers and of the ecumenical councils’.[[6]]

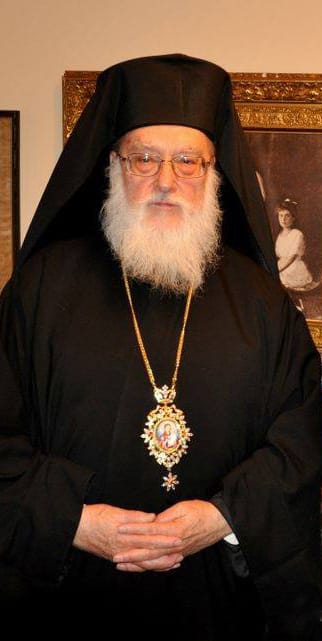

He was received into the Greek Orthodox Church in 1958. He studied classics and theology at Oxford University, attaining a double first. After spending some time in an Orthodox monastery in Canada and then the monastery of St John the Theologian in Patmos (Greece), he was ordained to the priesthood and tonsured a monk with the name Kallistos in 1966. That year he also launched a 35-year teaching career in Orthodox Studies at Oxford University where he was a Fellow of Pembroke College and also a long-serving parish priest serving both Greek and Russian congregations. In 1982, under the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, he was consecrated a bishop and elevated to the rank of metropolitan in 2007.

In 1963 Ware published his most widely-read book, The Orthodox Church (‘still the quintessential introduction to the Orthodox Church’[[7]]), which he reviewed and updated many times. A more seasoned and more spiritual book, The Orthodox Way, largely concerned with prayer, appeared in 1979. Ware was a prolific writer and many of his works harmonize scholarship and spirituality. His one-time student and friend, Fr John Chryssavgis, has written of ‘his rare combination of the scholarly and spiritual, academia and asceticism, of patristic literature and profound liturgy – of Orthodox Christianity as a living and life-changing tradition’. Chryssavgis remembers Ware primarily as the translator, with Mother Mary of the Orthodox Monastery of the Holy Veil in France, of The Festal Menaion and The Lentern Triodion, ‘the core liturgical books of the Orthodox Church’, completed in 1969 and 1977.[[8]]

With Gerard Palmer and Philip Sherrard, Ware worked on the landmark translation of the Philokalia, a compilation of mystical texts, and on other traditional patristic and liturgical works. The bishop was also for many years the editor of ‘the pioneering journal’, Eastern Churches Review. Just as Philip Sherrard had spent the last months of his life working on the Philokalia, so too Ware was finalizing the Index for the fifth and last volume just before he crossed to the Jordan.

Asked to state his understanding of the Christian message as succinctly as possible, Ware responded:

I believe in a God who loves humankind so intensely, so totally, that he chose himself to become human. Therefore, I believe in Jesus Christ as fully and truly God, but also totally and unreservedly one of us, fully human. And I would say to you, ‘The love of God is so great that Christ died for us on the cross. But love is stronger than death, and so the death of Jesus was followed by his resurrection.’ I am a Christian because I believe in the great love of God that led him to become incarnate, to die, and to rise again. That's my faith. All of this is made immediate to us through the continuing action of the Holy Spirit.[[9]]

Metropolitan Kallistos was an inspired preacher, an engaging lecturer and dedicated teacher, a prolific writer, a revered spiritual director. He was deeply involved in Christian ecumenism, especially Anglican-Orthodox. Discussing his commitment to ecumenism he recalled the early Christian saying unus Christianus, nullus Christianus (‘one Christian, no Christian’), explaining that

No one can be genuinely Christian in isolation. We are saved, not alone, but as members of the Body of Christ, in union with all other members. For me therefore, as a Christian, it is vitally important that I should seek to meet other Christians, to understand them and to work with them…[[10]]

He was a courteous, lucid and witty participant in all manner of dialogues, interviews, seminars and the like. He travelled several times to the USA where he was well-known in academic and Orthodox circles, especially within the orbit of St Vladimir’s Seminary in New York. In his later years the bishop didn’t flinch from engagement with volatile controversies about the ordination of women, the Church’s teaching on homosexuality and the unhappy developments in Orthodoxy triggered by the Ukraine-Russian war. He also critiqued ‘the ethnic narrowness and intolerance of Orthodoxy’ which often betrayed its true nature.

Chryssavgis affords us some glimpses of Ware’s personality, character and outlook:

He was a punctilious and measured man… Comfortable serving as a priest at Holy Trinity Church as he was researching in the Bodleian Library and chairing the faculty of theology, he spent countless hours visiting patients in hospitals and parishioners in restaurants or businesses. He was as much on fire delivering a lecture on the desert fathers or the Palamite controversy as he was delivering a sermon… all with a distinctive and ingenious wit… Thoroughly ecumenical, he was an English gentleman through and through. Orthodox to the bone, he nevertheless considered himself a perennial apprentice of the faith, once stating how he looked forward to browsing through heaven’s library. He never imagined himself contorting the Orthodox faith to personal conventions or apprehensions, but ever perceived himself as willing to be shaped, perhaps surprised by its newness… He emphasised the struggle to espouse the heart of the Orthodox faith as well as to embrace its paradoxes, antitheses and polarities.[[11]]

Another acquaintance described him as ‘genuinely good and caring, humorous (and frequently enjoying his own humor), intellectually curious, and strong in his faith and commitment to Orthodoxy while thoughtful and open-minded as he pondered the distinctions between Tradition and traditions in the face of our broader society’.[[12]]

In 2003 St Vladimir’s Seminary Press published Abba, The Tradition of Orthodoxy in the West; Festschrift for Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia in which we find articles encompassing many of Ware’s abiding interests.[[13]] In 2017 the Archbishop of Canterbury awarded him the Lambeth Cross for Ecumenism ‘for his outstanding contribution to Anglican-Orthodox theological dialogue’. Along with Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh (1914-2003),[[14]] he had become the best-known and most influential Orthodox theologian in the English-speaking world. After a serious illness Metropolitan Kallistos departed this life in 2022, aged 87. His death occasioned many fervent tributes from people from differing Christian traditions. As Maria Gywn McDowell, an American Episcopalian priest wrote, ‘A gracious, thoughtful, articulate spokesman for the best of Orthodoxy to an English-speaking audience has died.’[[15]]

Rather than essaying any summation of his work, here I want only to highlight three recurrent themes in the bishop’s life and thought which seem to me particularly fruitful, signposted by three resonant (and inexhaustible) terms: ‘mystery’, ‘theophany’, ‘tradition’ – a subjective and somewhat arbitrary selection; one might just as profitably focus on Ware’s explorations of ‘faith’, ‘worship’ or ‘prayer’, subjects on which he has ruminated and wisely written throughout his long Christian journey.

The Christian Mystery

We see that it is not the task of Christianity [Ware writes] to provide easy answers to every question, but to make us progressively aware of a mystery. God is not so much the object of our knowledge as the cause of our wonder.

How much spilling of blood, both figuratively and literally, might have been avoided if Christian theologians and ecclesiastical authorities had cleaved to this principle, one which has been repeatedly affirmed throughout the ages but all too often not sufficiently heeded. Here is Simone Weil on the same subject: ‘The mysteries of faith are degraded if they are made into an object of affirmation and negation, when in reality they should be an object of contemplation.’[[16]]

In similar vein, Karen Armstrong: ‘A theology should be like poetry, which takes us to the end of what words and thoughts can do.’[[17]] Ware again:

In the Christian context, we do not mean by a ‘mystery’ merely that which is baffling and mysterious, an enigma or insoluble problem. A mystery is, on the contrary, something that is revealed for our understanding, but which we never understand exhaustively because it leads into the depth or the darkness of God. The eyes are closed – but they are also opened.

Ware explains that we cannot understand God’s ‘inner being’ or ‘essence’ because to do so would be know God ‘in the same way as he knows himself’ which is not possible since there is a gulf between the Creator and the Created. Here Ware is actually contradicting the testimony of the mystics and ignoring St Iranenus’ dictum to which he himself actually refers elsewhere the same volume: ‘God became man that man might become God’. In the same vein Ware states that

God's Incarnation opens the way to man's deification. To be deified is, more specifically, to be ‘christified’: the divine likeness that we are called to attain is the likeness of Christ. It is through Jesus the God-man that we men are ‘ingodded’, ‘divinized’, made ‘sharers in the divine nature’ (2 Pet. 1:4).

Be that as it may, the incommensurability of ‘God’ and ‘man’ means that for all but the fully realized saint-mystic, God remains a mystery – but, paradoxically, a ‘revealed’ mystery, both in the person of Christ and in the cosmic theophany whereby we come to know the divine ‘energies, grace, life and power [which] fill the whole universe, and are directly accessible to us’.

The Cosmic Theophany

The Psalmist affirmed that ‘The heavens declare the glory of God; And the firmament sheweth his handiwork’ (Psalms 19.1), a theme which resounds through the Christian tradition. As Hildegard of Bingen put it, ‘There is the music of Heaven in all things’. In his writings Ware often articulates the same idea, seeing the whole universe as a cosmic theophany, a revelation of the ‘divine energies, grace, life and power’, each part not only ‘standing out in all the brilliance of its specific being’ but also ‘transparent’ so that in all created things and beings we may discern the Creator; to contemplate nature, to see with spiritual vision, is to see God everywhere. ‘God is above and beyond all things, yet as Creator he is also within all things –panentheism, not pantheism.’ Here Ware is rehearsing an idea to be found not only in the Abrahamic traditions but through the ages throughout the world. The Lakota holy man, Black Elk, was expressing precisely the same idea as the Orthodox bishop when he stated that

We should understand well that all things are the works of the Great Spirit. We should know that He is within all things: the trees, the grasses, the rivers, the mountains and all the four-legged animals, and the winged peoples; and even more importantly, we should understand that He is also above all these things and peoples. When we do understand all this deeply in our hearts, then we will fear, and love, and know the Great Spirit, and then we will be and act and live as the Spirit intends.[[18]]

Ware gives the principle a particular Christian inflection in seeing Christ (as Logos) as the divine unifier:

He is the principle of order and purpose that permeates all things, drawing them to unity in God, and so making the universe into a ‘cosmos’, a harmonious and integrated whole. The Creator-Logos has imparted to each created thing its own indwelling logos or inner principle, which makes that thing to be distinctively itself, and which at the same time draws and directs that thing towards God.

The Living Tradition

As intimated earlier, one of the attractions of Orthodoxy for Ware was a ‘vibrant and vivifying conception of Tradition’ the strong sense of ‘a living and unbroken continuity with the Church of the Apostles and Martyrs, of the Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils’.[[19]] Here just two points about ‘tradition’: a proper understanding of the term includes the notion that far from being a fossilized deposit from the past, any religious tradition properly so-called is, in Ware’s words,

not static but dynamic, not defensive but exploratory, not closed and backward facing but open to the future… The only true Tradition is living and creative, formed from the union of human freedom with the grace of the Spirit.[[20]]

In Vladimir Lossky’s words, ‘Tradition is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church’. Ware’s understanding of ‘tradition’ was, by his own account, much influenced by two of the greatest Orthodox theologians of recent times, Pavel Florensky (1882-1937) and Vladimir Lossky (1903-1958). Mention may also be made of Aleksei Khomiakov (1804-1860) to whom Ware also often referred. (Younger folk might protest that these figures are not ‘recent’ but indeed they are if we are thinking in traditional terms!) Ware’s thinking and writing is everywhere saturated with familiar references to the Orthodox tradition; he is on intimate and friendly terms, so to speak, not only with the Scriptures but with the Fathers, the mystics and saints, the great theologians and philosophers, with the rich liturgical heritage, indeed with pretty well all aspects of the tradition. As Seyyed Hossein Nasr has so well put it,

Tradition is inextricably related to revelation and religion, to the sacred, to the notion of orthodoxy, to authority, to the continuity and regularity of transmission of the truth, to the exoteric and the esoteric as well as to the spiritual life, science and the arts.[[21]]

Ware has immersed himself in all these aspects of ‘tradition’. No doubt he would have endorsed Lord Northbourne’s claim that ‘tradition is the chain that joins civilisation to Revelation’.[[22]] The ‘unbroken continuity’ to which Ware refers is vouchsafed by the principle from which the Eastern Church takes its name, that of orthodoxy, usefully defined by Frithjof Schuon as ‘the principle of formal homogeneity proper to any authentically spiritual perspective’.[[23]]

In ancient Greek ‘Kallistos’ means something like ‘the most beautiful’ or ‘the best’, a name Timothy Ware assumed at his monastic tonsure and priestly ordination. How apposite the name was. In one of his many interviews the bishop asserted that ‘Tradition lives on. The age of the fathers didn’t stop in the fifth or seventh century. We could have holy fathers now…’.[[24]] He would certainly not have made any such claim for himself but he was one such.

Principal Sources

Metropolitan Kallistos wrote a number of scholarly books and articles about many aspects of Orthodoxy, some of them quite arcane, but The Orthodox Way (London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1979) comprises the quintessence of his teaching while The Orthodox Church (Penguin Books, 1963) remains a go-to work on the tradition as a whole. Strange Yet Familiar: My Journey, published on-line in three parts by the journal Journey to Orthodoxy, gives an account of his conversion to Orthodoxy. Presently only one of a projected six volumes of Ware’s collected works has been published: The Inner Kingdom: Volume 1 of the Collected Works (New York: St Vladimir’s Seminary, 2000). Various interviews, lectures and obituaries can be easily ferreted out online.

[[1]]: Excerpted from Harry Oldmeadow, Persons of Interest: People, Books, Ideas, Encounters, Carbarita Press, 2023

[[2]]: All quotes from Ware, unless otherwise indicated, come from The Orthodox Way, Mowbray, 1979

[[3]]: Helen Waddell, The Desert Fathers, first published 1936

[[4]]: Ware’s conversion to Orthodoxy is described in Strange but Familiar: My Journey, published online in three parts by the journal Journey to Orthodoxy. The first part (with links to Parts 2 & 3) can be found at: journeytoorthodoxy.com/2010/07/strange-yet-familiar-my-journey-to-orthodoxy-part-1. There are several different versions to be found online. The excerpt above – hereafter referred to as Strange Yet Familiar – comes not from the Journey to Orthodoxy site but from the Seattle Pacific University site: stories.spu.edu, further citations from which will be signalled by My Journey

[[5]]: Strange but Familiar Pt 1

[[6]]: My Journey

[[7]]: John Chryssavgis, “Lifestory: Remembering Kallistos Ware, revered Orthodox Christian theologian,” sightmagazine.com.au, 25 Aug 2022

[[8]]: “Lifestory: Remembering Kallistos Ware”

[[9]]: Interview with David Neff, July 6, 2011; Christianity Today (online)

[[10]]: My Journey

[[11]]: “Lifestory: Remembering Kallistos Ware”

[[12]]: Valerie Karras, “In Memoriam: Metropolitan Kallistos Ware of Diocleia,” 25 Aug 2022; www.wheeljournal.com

[[13]]: The festschrift is edited by John Behr, Andrew Louth and Dimitri Conomos

[[14]]: For an introduction see Gillian Crow, This Holy Man: Impressions of Metropolitan Anthony, St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. His best-known works are Living Prayer and God and Man

[[15]]: “May Our Hope Not Die With You Metropolitan Kallistos Ware,” womenintheology.org, 29 Aug 2022

[[16]]: From Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, first English edition 1952

[[17]]: “Karen Armstrong Builds A ‘Case for God’”; npr.org/2009/09/21/112968197/karen-armstrong-builds-a-case-for-god

[[18]]: Black Elk’s words are to be found in Joseph Epes Brown, The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux, 1989, xx

[[19]]: Strange Yet Familiar, Pt 2 (italics mine)

[[20]]: Strange Yet Familiar, Pt 3

[[21]]: Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred, 1981, 68

[[22]]: Lord Northbourne, Religion in the Modern World, 1963, 34

[[23]]: Frithjof Schuon, Stations of Wisdom, 1961, 13

[[24]]: Interview with David Neff