The facts, statements, and quotations that Mark Perry presents in Uprooting the Vineyard: the fate of the Catholic Church after Vatican II, as well as his commentaries and conclusions, are the result of more than ten years of research and reflection. He has transformed these into a unique work, unparalleled in the growing bibliography about the position of the Catholic Church in the contemporary world since the fateful revolution that was the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) — a revolution which, according to some of its promoters, was as momentous as the French Revolution of 1789 or the Russian Revolution of 1917. The truth is, it was an internal demolition, or the implosion of a religious edifice over two thousand years old; a self-destruction conceived, planned, and ultimately carried out by the very people who should have kept the edifice standing.

Even so, it is surprising that this palace revolution—since it wasn't a revolt of people in the streets, but rather of the highest clerical leadership, including popes, cardinals, bishops, theologians, and so on—did not provoke a reaction from the majority of Catholics, who have been generally passive in the face of changes in their religion's creed and cult. This revolution has been moreover opposed only by a minority, the so-called "traditionalists." Perry focuses on the behind-the-scenes, so to speak, and the roots of these transformations, which date back to the Renaissance period.

The Uprooting

no other study … analyzes in such depth and scope the transformations wrought over the past 60 years since the Council concluded its sessions in 1965

The central thesis of the volume is that the virtually impregnable citadel of tradition and orthodoxy that the Church embodied for two millennia was infiltrated, and ultimately poisoned from within, an operation carried out by intra-ecclesiastical anti-spiritual forces whose watchwords were, and still are, aggiornamento, updating, reconciliation, or pact with a secularist modernity that is as far as possible distant from the Sacred, religion, and spirituality. Perry shows how this new and unexpected pact established by the Council is at the root of the intellectual and moral destabilization of the Western world, in direct confrontation to its ancestral and well-established certainties. Nevertheless, as William Stoddart assessed in the Foreword, “few will dare to resist Perry's unrelenting onslaught” on the “Golden Calf” of Vatican II, but “all will be enlightened” and rewarded.

I know of no other study that analyzes in such depth and scope the transformations wrought over the past 60 years since the Council concluded its sessions in 1965, and the Western world, whose main religious and spiritual center is the Catholic Church, began to feel its destabilizing impacts. The consequences of the Council’s beliefs and ideas and its aftermath have been devastating, especially in what concern the spiritual and moral lives of generations of believers. Perry analyzes with rigour and extraordinary subtlety the main themes of this disguised religious revolution, not yet properly perceived as such by the majority, such as the primacy granted to “human rights”, to the detriment of God’s rights; the concertation with, and de facto submission of the Church to, modernistic, atheistic and/or agnostic science and philosophy; the adoption of "believing" forms of Darwin's scientistic theory of evolution incorporating its anti-archetypal conjectural elements, which directly and completely challenge the biblical and revealed doctrine of human origins, as in the case of the fanciful theories of Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955).

This Jesuit priest was the main promoter of Darwinian evolutionism inside Catholicism, and despite being censured by the pre-Conciliar authorities, de Chardin was posthumously rehabilitated – Perry notes that he was first rehabilitated by John XXIII, and then by Cardinal Ratzinger, as shown in his book Introduction to Christianity, and later as Benedict XVI in his Spirit of the Liturgy. Frithjof Schuon observed, “The speculations of Teilhard de Chardin provide a striking example of a theology that has succumbed to microscopes and telescopes, to machines and to their philosophical and social consequences, a ‘fall’ that would have been unthinkable had there been here the slightest direct intellective knowledge of immaterial realities.”(Understanding Islam, p. 21.)

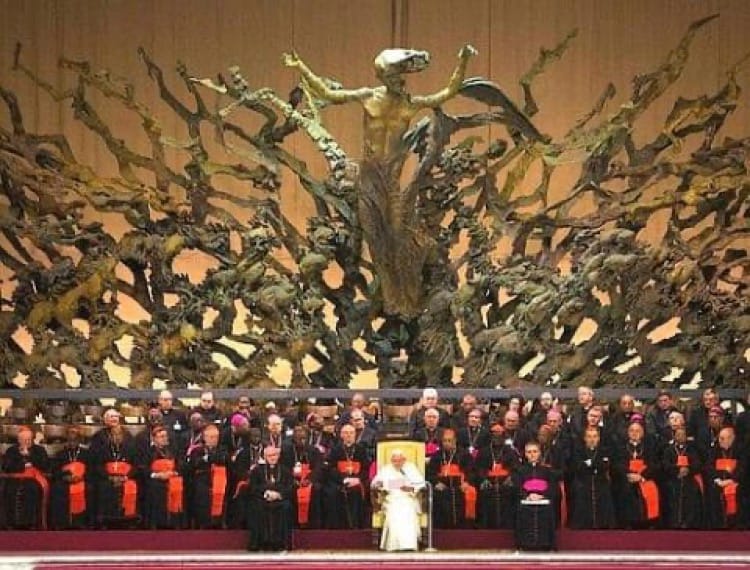

One visual indicator of the Council’s pandering to modernism is found in its encouragement and sponsorship of modernistic art and architecture, lacking the symbolist discernment of Tradition. Examples of this are the Paul VI Audience Hall, opened in 1971 at Vatican City, with its surrealist sculpture showing a deformed Christ emerging from supposedly atomic destruction, and the sinisterly reptilian internal architecture of the space (see images below).

All this and more: the anti-modernist structure of the ancient church, including its venerable liturgies, which today barely subsist, thanks largely to the tireless struggle of a few priests and faithful who promote them as best they can, is being undermined by the steamroller of Vatican authorities who, like the last pontiff, seek in every way to eliminate them.

What is Modernism?

Modernism, in effect, has lost the sense of the Sacred.

As we speak of ‘modernism’ as the major force in shaping contemporary Catholicism, it will be helpful here to discuss this important concept. The opposition to the traditional expressions of the Sacred transmitted through Revelation has existed through recorded history. However, in recent times it has regained strength through certain ideological influences driven by philosophy and modern science which have overvalued Man at the expense of the Sacred. These anthropocentric influences were heightened during the so-called Renaissance, when the traditional worldview was questioned by science and rationalism, and, with the advent of industrialization and its aftermath, these influences became endemic in the ‘wasteland’ of the modern world.

Modernism, in this sense, emerges at the turn of the 19th and the 20th centuries, and aims to overcome the past and tradition in the search for new ways of understanding and interpreting reality, religion, art, etc., adopting a decisive pro-modern Weltanschauung opposed to Tradition in the sense of the perennial wisdom traditions. Modernism aims to reconcile faith and reason, tradition and modernity, inevitably underestimating the first element and overestimating the second. Rationalism, scientism, and individual experience and subjectivity prevail in its reinterpretation of faith, scripture and religious traditions. It fundamentally believes in “progress” (in reality, ‘progressivism’) and in the constant and inevitable “evolution” of humanity (leading to a decentering ‘malaise’), and underestimates Tradition and the authority of ancient sages and saints. Modernism, in effect, has lost the sense of the Sacred, and this is one of its defining characteristics. It seeks to reinterpret traditional doctrines and teachings principally in the light of modern experience, philosophy, and science. Finally, with regard to religion, it overestimates the sociological and historical aspects of religion, to the detriment of theology, mysticism, and perennial wisdom. René Guénon criticized modernism in the following way:

“Any compromise between the religious spirit and modern mentality would weaken the former and would benefit only the latter, whose hostility will not at all be diminished by this, given that modernism aims at the total annihilation of all that, in humanity, reflects a higher reality than her.” (Crisis of the Modern World, chapter 6].

For his part, Pope Pius X (1903-1914) defined modernism as the “synthesis of all heresies” (in his encyclical Pascendi, 1907).

Frithjof Schuon observed that “modernism does not begin with the heretics of a theological or mystical type, it starts with the rationalist and skeptical philosophers, such as Bacon or Hobbes, and especially with the Encyclopedists; or, which amounts practically speaking to the same, it starts with modern Freemasonry” (unpublished document). He notes that “modernism cannot derive from Catholicism in itself, but on the contrary has taken possession of it and makes use of it like an occupying power.” (Esoterism as Principle and as Way, p.19. Perennial Books, 1981.)

Mark Perry has this to say: "modernism—which is secularism taken to an exponential extreme—threatens all of the great faiths, not just Catholicism. Indeed, spirituality and modernism are as antithetical as frankincense and soot, and thus no believer can hope to approach the Divine effectively without first disavowing modernism, because its inherent secularism, when not offensive profanity, is incompatible with the holiness of the kingdom of Heaven." (p. 107)

Perry writes in the spirit of Christ in the Gospels: "You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”

Mark Perry is particularly suited to the Herculean task of unraveling the machinations and unforeseen consequences of the transformations wrought in the Weltanschauung and in the praxis of Catholicism by Vatican II. Surprisingly to some, his fundamental perspective is not the theological exclusivism of religious traditionalism, but the universality of the Perennial Philosophy—a school of thought led in the 20th century by visionary metaphysicians such as the aforementioned Frithjof Schuon and René Guénon, and others like Titus Burckhardt, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Marco Pallis, Martin Lings, William Stoddart, and S.H. Nasr. Nevertheless, the volume is dedicated to the popes immediately preceding the Council who strove to keep the Church on the path of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty, such as Pius IX, Pius X, Pius XI, Pius XII, Leo XII, and Gregory XVI.

Mark is the son of the renowned Perennialist essayist Whitall Perry (author of A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom), who lived in Cairo, where Mark was born in 1951, and was part of René Guénon's circle. With the latter's death in this same year, the Perry family moved to Lausanne, Switzerland, where Schuon lived. Thus, Mark had the privilege of spending time with Frithjof Schuon and his Perennialist circle during his childhood and youth, and it was this closeness that ultimately led him to dedicate ten years of research to the topic, following in the footsteps of the commentaries and letters Schuon wrote over many years on the subject. Uprooting the Vineyard includes a rich appendix of Schuon's correspondence, documents that served as a starting point for Mark Perry's work.

Uprooting the Vineyard is the most deeply researched, incisive, and compelling account of the consequences of “the Latin Church's fateful compromise with the false ideals, philosophies, and misconceived values” transacted at Vatican II, as Harry Oldmeadow noted in the book cover. It offers a fascinating exposition of everything important related to the Council, providing us with coherent insights and many examples of modernist trickery and cunning.

The religious subversion that wreaked havoc on a once orthodox and traditional institution has found in Mark Perry an interpreter apt for the enormous challenges of exposing the ‘uprooting of the vineyard.’ His work will be remembered for its persevering and intelligent, and courageous, exposition of the truth, no matter the discontent with which it will be met in some quarters. Perry writes in the spirit of Christ in the Gospels: "You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”