AD MAJOREM DEI GLORIAM

You feel like talking to someone

Who knows the difference between right and wrong

—David Byrne, “What a Day That Was,” from The Catherine Wheel

It might seem out of place to begin an essay with a line from a pop song. But the Book of Jonas, the main subject of this article, ends with God asking why He should not spare a people who cannot distinguish their right hand from their left, having already spared a hard-headed prophet. The line is therefore fitting. This essay seeks to clarify precisely that distinction. My aim is simple: to restore a traditional understanding of Baptism and Confirmation through the initiatic structure embedded in the Jonas narrative. My thesis is direct: the Book of Jonas contains two initiations—a first of descent (Water and Earth), corresponding to Baptism, and a second of ordeal (Air and Fire), corresponding to Confirmation. These two movements—enclosure and exposure, shadow and light—constitute the grammar of Christian initiation. Modern Catholic theology has largely lost this grammar.

I propose that the Church is in deep trouble regarding the understanding of her own sacred history. Readers interested in the recent history of Catholicism are likely aware of the importance of the ‘New Theologians.’ While their methods vary widely, one thing that stuck was the naturalization of theology. Or better yet, a renewal of naturalism within theology.

That is the case of Fr. Jean Daniélou. This Jesuit produced some of the finest research on the remote origins of Christian symbolism, such as Les Symboles chrétiens primitifs (1961). While his work offers new and needful light on some intricate symbols and Catholic practices, such as the Baptism by triple immersion[[1]], his theory of the symbol is entirely off the mark from a traditional standpoint. In his view, the Christian sacraments derive from pagan rituals, established by “some syncretism.” The reason lies in the “striking similarities” among diverse pagan religions with Catholicism, leading them to adopt the same natural symbols. So man “refigures his communion with God in a field, refigures the purification of sins by immersion in waters, symbolizes the partaking of a mysterious force with anointing with oil.” These things are “common to every religion because in reality they express a natural symbolism, and it is usual to found religious symbolism from natural symbolism.”[[2]]

Readers familiar with Traditionalism or the broader trado-perennialist school can see at once why this vision is mistaken.[[3]] Firstly, it calls for a mundane version of syncretism—that in the end all religions are one because there is really just one big earth religion (a backward reading of the idea of Tradition as construed by Guénon).[[4]] Secondly, it essentially packages for Catholic academic consumption Sir James Frazer’s idea that nature directs religion, thereby calling for a mundane notion that all religions are one. For instance, water makes things clean, so if you wash your soul in water, water will make it clean. The corollary is that water is a deity. In time, sophistication will filter out matter and just the religious ritual will remain. Spirit springs from nature.

the symbolic power of the natural elements come from a vertical command

Daniélou’s ideas were met with enormous success in the mid-twentieth century, including within the Church. The end result is that Daniélou’s way of seeing symbolism as a historical starting point of religious intuitions made its mark in Roman Catholicism. Over time, even the Church hierarchy began to lose the ability to interpret the symbols of the faith within traditional boundaries, especially in regard to Scripture interpretation. One of the effects is that the sacraments lose their meaning, effectively becoming mere rituals driven by custom. In an era that holds little regard for sacredness this is particularly dangerous because religious rites only remain alive insofar as someone still knows their meaning. Their vulnerability increases with their complexity—either to perform or to understand their importance. Of the initiatic sacraments of the Church, none is as complex as Confirmation. Therefore none has been diminished to the same extent.

I seek with this a twofold goal: Firstly, for Catholic readers, remind that if indeed our sacraments have a history, it is above all a sacred history and the symbolic power of the natural elements come from a vertical command. That means to say, if water or fire are symbolic, the symbolic import comes from the existence imparted by the command of God. Thereby partaking in the sacraments means participating in this timeless sacred history. Secondly, for readers of other religions, the importance of this essay is of comparative religion. The symbols here studied are fairly common across religions and the meaning they have in the Roman Catholic religion might have the same magnitude in the reader’s own. Besides, with the generalized crisis in most religions of the world, a study on symbolism and rites can have inspiring effects.

Water and Earth

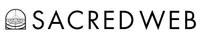

Prophet Jonas’ book is among the shortest in the Old Testament. God commands this prophet to go to Ninive, capital of the Assyrian Empire, and preach to the people there, “for the wickedness thereof is come up before me.” (Jonas 1:2, Douay–Rheims) Jonas flees and boards a ship bound for Tharsis. God then sends a great storm and the ship is at risk of capsizing. The sailors—heathens—pray to their gods while Jonas goes down to the hold of the vessel, where he sleeps as the storm rages.

The shipmaster finds him and asks him to pray to his God: “[C]all upon thy God, if so be that God will think of us, that we may not perish.” (1:6) Despite their efforts, including throwing the ship’s cargo overboard, the storm will not cease until they cast Jonas into the sea. “Take me up,” the prophet says, “and cast me into the sea, and the sea shall be calm to you: for I know that for my sake this great tempest is upon you.” (1:12) So they do this. Jonas falls into the sea and a big fish swallows him. There he remains for three days.

Inside the big fish Jonas prays for the Lord. This famous canticle, though prayed in the belly of a fish deep in the sea, is marked by water and earth symbolism: “And thou hast cast me forth into the deep in the heart of the sea, and a flood hath compassed me: all thy billows, and thy waves have passed over me” (2:4), “The waters compassed me about even to the soul” (2:6), “I went down to the lowest parts of the mountains: the bars of the earth have shut me up for ever” (2:7), “I shall see thy holy temple again… I remembered the Lord: that my prayer may come to thee, unto thy holy temple.” (2:5, 8).

descent is integral to the development of the wise man’s soul

While I believe this story is familiar to most readers, it is worth describing it again because we can easily overlook its symbolism. Jonas’ flight is what precipitates his ordeal. The narration is very clear: “he went down to Joppe” to flee from the Lord. The phrasing “he went down” (yāraḏ) means a descent in character or inwardly. The phrase also appears when Moses descends from Sinai with the Tables of the Law (just before he breaks them in anger, Exodus 32:15) and is used again at the beginning of David’s story in I Kings 1:1, when David goes “down into the wilderness of Pharan.” In both instances the protagonists are on the cusp of an initiatic ordeal. Moses has to dismantle the cult of the golden calf, David is called to be a king, and Jonas a prophet. Outside sacred literature, Socrates, in The Republic, was also “going down”: katebēn (“I went down,” 327A). As political philosopher Eric Voegelin comments:

‘Socrates walked down the five miles from the town to the harbor…. In the depth that held him he embarked on his inquiry and he used his persuasive powers on his friends not to let him free to go back to Athenas, but to make them follow him to the polis of the Idea. [The descent] recalls the Homer who lets his Odysseus tell Penelope of the day when “I went down [katebēn] to Hades to inquire about the return of myself and my friends,” and there he learned of the measureless toil that still was in store for him and had to be fulfilled to the end… [T]he Piraeus, to which Socrates descends, is a symbol of Hades. The goddess whom he approaches with prayer is the Artemis-Bendis, understood by the Athenians as the chthonian Hecate who attends to the souls on their way to the underworld.’[[5]]

The descent is integral to the development of the wise man’s soul, complementing the night-to-morning (that is, the transformative aspect of initiation) timeframe of the narrative. Most initiatic narratives imply descent and darkness-to-light transition. As Martin Lings puts it:

‘Now the descent into Hell for the discovery of the soul’s worst possibilities is only necessary because these possibilities are an integral part of the psychic substance and need to be recovered, purified, and reintegrated, for in order to be perfect the soul must be complete.’[[6]]

When Jonas finally submits to God’s will it is then, and only then, that he starts to be, and so begins his conversion

Jonas’ descent reaches far beyond Joppe, plumbing all the way into the belly of the fish. This is the earth symbolism in the first part of the story. It is the prophet’s own prayer that levels the cave and the belly of the fish. To quote Lings again, “in some traditional stories the descent into Hell is represented by a journey into the depths of the earth in search of hidden treasure.”[[7]] In Jonas’ case there is no hidden treasure as such but the prophet’s own faith in the Lord. It is in the bowels of the fish that he finds himself again—or, to put in another manner, “becomes himself,” going through what can be seen as akin to Hinduism’s tapas. It should be plain to see why this first part of the story is related to Baptism, for Baptism is self-realization; more precisely, it is the oath one makes to follow the revealed Law. This is why it is usually understood as an equivalent of the “lesser mysteries.”

It’s understandable that for non-Catholics this might pose a problem, since we—the viewpoint of this article is Roman Catholic—baptize infants. But as this is not an essay in apologetics I will refrain from asking whether this is right or wrong. Jonas’ descent into the whale is therefore clearly a manifestation of Baptism. Man is made into a child. Like all the faithful, God calls upon Jonas to become a member of His ranks; in this case to address the world about the coming of His Son. It is important to point out that this is the true meaning of the word ‘prophet’—the one who speaks on behalf of someone or something (pro, "on behalf"; phēmi, “to speak”). However, the objective is less about speaking than about participating ontologically in the mystery of God. By his participation, he grows in knowledge, and by knowing, he starts to be. It is unfortunate that in English the word ‘knowledge' has become associated with bookish knowledge; to avoid misunderstanding, let us clarify that by 'knowledge’ we are referring to the precise term René Guénon uses about "religious" knowledge: connaissance (which he derives from the Hindu concept of jñāna).[[8]] “‘Knowing’ and ‘being,’” he says, “are two sides of a same reality.”[[9]] When Jonas finally submits to God’s will it is then, and only then, that he starts to be, and so begins his conversion: “Metanoia is, then, a transformation of one’s whole being; from human thinking to divine understanding. A transformation of our being, for as Parmenides said, ‘To be and to know are one and the same,’ and ‘We come to be of just such stuff as that on which the mind is set.’ To repent is to become another and a new man. That this was St. Paul’s understanding is clear from Ephesians 4:23, ‘Be ye renewed in the spirit of your mind.’”[[10]] Much as Hamlet in his soliloquy, Jonas has to choose between being and not being—to die, to sleep, perchance to dream, or to be awake and start the upward journey to the Wisdom (Sophia) of God?

He submits and God commands the fish to vomit him out, thereby ending the initiatic cycle of Earth and Water.

Air and Fire

God again commands Jonas to go to Ninive to preach to the people there about the destruction of the city. This time the prophet obeys. The book describes it is a “three days’ journey” city, evidently foreshadowing the three days marking Christ’s death, harrowing of Hell, and resurrection. Unlike many other instances in the Old Testament, the people of Ninive repent on the very first day of Jonas’ preaching: “And the word came to the king of Ninive; and he rose up out of his throne, and cast away his robe from him, and was clothed with sackcloth, and sat in ashes…. And the men of Ninive believed in God: and they proclaimed a fast, and put on sackcloth from the greatest to the least.” (3:6, 5) The king adds that God’s will is unfathomable and His mercy is unending: “Who can tell if God will turn, and forgive: and will turn away from his fierce anger, and we shall not perish?” (v. 9) For the Christian reader, this also foreshadows God the Son’s mercy: when Jonas says, “And God saw their works, that they were turned from their evil way: and God had mercy with regard to the evil which he had said that he would do to them, and he did it not” (v. 10), he clearly anticipates the forgiveness Christ would show the St. Dismas—who states, “And we indeed [are punished] justly, for we receive the due reward of our deeds; but this man hath done no evil.” (Luke 23:41). For his act of penitence, Jesus rewards Dismas with paradise (v. 43), as God now rewards Ninive with His restraint and mercy.

As the text demonstrates, Jonas is “exceedingly troubled” (Jonas 4:1). This is important if we are to understand the meaning of Confirmation, both in its superficial as well as its deeper meanings. God spared Ninive for the opposite reason he makes Jonas go through a new ordeal. The last verse of the book discloses the meaning: “[S]hall I not spare Ninive, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons that know not how to distinguish between their right hand and their left, and many beasts?” (v. 11). We shall return to the significance of this verse later, but let it suffice for now to underline that the Lord is remarking that Ninive’s people are ignorant; that is to say, deprived of knowledge (a-gnostos).

To return to the narrative: Ninive prays to the Lord and moves God from violence to mercy. God’s sparing of the people angers Jonas. He prayed to God to let him die. This passage is mystifying at first: why would the prophet rather die than see such a large city—over 120,000 people and “many cattle”—spared from destruction? According to the Church Fathers, Jonas not only had suspected from the beginning that God would not destroy the city but he felt that the Lord had led him to proclaim a false prophecy: “On a certain occasion, Jona was also sorely grieved for having lied at the bidding of God.” (St. Jerome, Against the Pelagians, III; FC 53:357)[[11]] Bold words from St. Jerome. But the very next sentence helps us understand the difference between initiation and spiritual growth: “but he is convicted of an unjust grief.” (Ibid.) As St. John Chrysostom puts it, Jonas’ intuition from the beginning was precisely that the Lord would spare the Ninevites: “When he saw that three days had passed and nothing had happened anywhere near what was threatened, he then put forward his first thought and said, ‘Are these not my words that I was saying, that God is merciful and long-suffering and repents for men's evils?’” (On Repentance and Almsgiving, II, 20, FC 96:23) Most Church Fathers agree that either the prophet expected Ninive to backslide (St. Cyril of Alexandria, On Jonas, IV, 5, FC 116) or he was angered to see God have mercy on Gentiles. This is St. Augustine’s view: “[T]he salvation of penitent nations is preferred to [Jonas’] suffering.” (Letter CII, 6, FC 18:174).

The prophet has been initiated, but he does not understand. Even though he knows that the Lord would spare the Ninevites if they amended their ways, Jonas cannot bring himself to understand why God would send a false prophet to make a fool of himself in so large a city. Herein lies, one might say, the difference between exotericism and esotericism. The Gentiles of Ninive are now following the law. What law, though, if they are Gentiles? It is evident that the law under discussion cannot but be the moral law. Catholic dogmatic theology defines “moral law” as that which “addresses the common good as prescribed to each member of a society; it fights evil by threats of punishment,” and so on. Though having as its source the “legislative power,” it is not anything other than “the expression of the divine will.”[[12]] Since a law must be dispensed, someone must legislate it. Hence the necessary figure of the Lawgiver, which the Ninivites intuit. Like Plato, they lived before the Revelation, so they did not know God. But they understood, like Plato, that there is a universal moral law that the Lawgiver promulgates (“this god… sits in the middle of the earth at its navel and delivers his interpretations,” The Republic 427B) and that the law-abiding man—that is, the moral man—fashions himself after the law.

Salvation in the general sense requires following the law. Spiritual growth requires intellectual ascent.

We can now drive home the point made above that Baptism is akin to an initiation in the Lesser Mysteries, for it makes obligatory following the external or “social” aspects of a religion: “The knowledge of the smṛti, that is to say of the applications to the ‘world of man,’ understanding by this the integral human state, considered in the full range of its possibilities, constitutes the ‘lesser mysteries.’”[[13]] It is not necessary that he understands it; that is the role of the esotericist. It is only necessary that he patterns himself after the law, conforming to its model.

Thus the esotericist does and obeys. Since Christianity does not have a clear-cut division between esotericism and exotericism (the degree of inwardness is, as Rama Coomaraswamy said, measured as though by a sliding rule)[[14]]; yet he who seeks wisdom must understand. The deeper meaning of the Law also requires its own initiation. Salvation in the general sense requires following the law. Spiritual growth requires intellectual ascent.[[15]] Now God, Who is Truth and Wisdom Himself is pure burning light. Since Jonas, despite his anger at God, does not renounce the Lord, yet he must be humbled since he prefers his own human will over God’s will. Not only does he refuse to understand, but he also tries to bargain with God so he can be made a saviour. So, according to St. Jerome, when Jonas asks to die, he is in essence saying “while living, I was unable to save the one nation of Israel; I shall die, and the world will be saved.” He continues, “The story is clear and can be understood of the prophet who, as we have said many times, grieves and wishes to die, so that the conversion of the multitude of the Nations might not bring about the definitive loss of Israel.” (D291)

How does God resolve matters? Jonas leaves Ninive and goes to a nearby hill to see what will happen. God grows an ivy—the qîqāyôn—so the prophet remains in the shade. Some commentors like Augustine emphasize that the ivy’s shadow was “the promises of the Old Testament, or even those obligations in which there was manifestly, as the Apostle says, ‘a shadow of things to come’ [Col 2:17; Heb 10:1].” (St. Augustine, Letter CII, 6, FC 18:174) More generally we can see in this shadow the symbol of the moral law whose origin is still unrevealed; for Christians, unrevealed because Christ the Redeemer is not yet come, for Muslims because Prophet Muhammed is yet to bring the age of the prophets to an end (the exact nature of ‘revelation’ in the light of Tradition warrants an essay unto its own; the discussion on the subject still is very incomplete), and so on. Yet, as Guénon and most Christian commentators stress, wisdom is an action of the Holy Ghost, as Spirit and Light: “The śruti is direct light, which, like pure intelligence, which here is at the same time pure spirituality, corresponds to the sun.”[[16]]

God’s next action is now clear: after nightfall, He sends a worm to eat away the ivy. The plant that had shaded Jonas withers and dies and consequently on the next day sun and wind terrorize Jonas: “And when the sun was risen, the Lord commanded a hot and burning wind: and the sun beat upon the head of Jonas, and he broiled with the heat: and he desired for his soul that he might die, and said: It is better for me to die than to live.” (Jonas 4:8)

The presence of the ivy recalls the earthly, "mundane," so to speak, aspect of Baptism. Sun and wind are evidently manifestations of the symbolism of Fire and Air. Those familiar with the Gospel will recall that the sun and wind play meaningful roles in the Incarnation, especially in the episode of the Transfiguration.

The final verses of Jonas’ book are even more mystifying. The prophet complains that God took the ivy away: "I am angry with reason even unto death” (Jonas 4:9). These are words Christ recalls with justice in Gethsemane:“My soul is sorrowful even unto death” (Matthew 26:38, Mark 14:34). Meanwhile, the Lord rebukes Jonas: he did not plant and grow the ivy; it was a gift from the Highest, which God has the privilege to withdraw. Recalling Job (1:21), ‘The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away’. And if God has spared Jonas’ life, who angers over decisions that are not his, why should God not spare the lives of the people of Ninive, who are in ignorance and unable to tell their right hand from their left?

Conclusion

Sacraments, in particular the two initiatic sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation, invite us to awaken from death into life

With this essay we have aimed to make clear that Baptism and Confirmation are sacraments that initiate a deeper reality. Sacraments, in Catholicism, are not “symbols.” They carry meaning; they are vectors of the Holy Ghost. To use the words of Mircea Eliade, they have power: “The man of archaic societies had the leaning of living as close as possible in the sacred or in the intimacy of consecrated objects…. [F]or the ‘primitives’ and for men in every premodern society, the sacred was equivalent to power, and, in essence, to reality itself. The sacred is saturated with being.”[[17]] Thus sacraments are far more than symbolic acts or symbolic rituals—especially if by symbolism we mean merely some naturalistic repetition of an old ritual of an ancient religion whose sacramental meaning has long since vanished.

Sacraments, in particular the two initiatic sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation, invite us to awaken from death into life. Jonas, by insisting that he be allowed to die, is in fact truly dead. George Tyrrell once wrote, “I begin to think that the only real sin is suicide or not being oneself.” Reflecting on this, Marco Pallis observed, “his statement contains echoes of a doctrine of universal scope—from which all its relative validity at the individual level is derived—namely, that the ultimate and only sin is not to be One Self, ignorance (avidya) of What one is, belief that one is other than the Self.”[[18]] Jonas’ will is, both at the beginning and at the end of his book, at variance with God’s, Who is the source of reality as well as the ultimate reality itself: alpha and omega. Becoming oneself is, as Pallis says, becoming One Self. And if God is the truly Real, His sacraments are Reality and they make Reality. Thus it is of supreme importance that we should understand what the symbolism of the sacraments and that His Church should understand and communicate, in this age of confusion for her, what is it that the sacraments truly offer, and so minister to people.

Victor F. Bruno is a researcher and writer working on the intellectual traditions of the West, with particular attention to Catholic and Spanish traditionalism. He is the author of René Guénon Revelado (2023) A Imagem Estilhaçada (2020), and of the popular Cartas da Tradição newsletter on Substack. He lives and works in Brazil.

[[1]]: See Jean Daniélou, S.J., L’Église des premiers temps (Paris: Seuil, 1985), ch. 6.

[[2]]: Jean Daniélou, S.J., Miti pagani, mistero cristiano, trans. Maria Rita Paluzzi and Paolo Piazzesi (Rome: Arkheios, 1995), 30.

[[3]]: As to why this term see Victor Bruno, René Guénon Revelado: Vida e Pensamento de um Enigma do Século XX (Curitiba: Danúbio, 2023), 94ff.

[[4]]: On the problems of syncretism, René Guénon, Perspectives on Initiation, trans. Henry D. Fohr (Ghent, N.Y.: Sophia Perennis, 2004), 37–47.

[[5]]: Eric Voegelin, Order & History, vol. 3, Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, 16 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000), 107–108; in-text references elided.

[[6]]: Martin Lings, Shakespeare’s Window into the Soul (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2006), 75.

[[7]]: Ibid., 79.

[[8]]: I am aware that in Traditionalism there are no “Hindu” concepts as such, but universal doctrines that take this or that particular formalization in existence; but, as mentioned above, it can be a temerity to use concepts from one religion wholesale into another without accounting for adjustments based on “local color” and the general “temperament” of the latter.

[[9]]: René Guénon, Les États multiples de l’être (Paris: Véga, 2009), 120.

[[10]]: Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “On Being in One’s Right Mind,” in Samuel Bendeck Sotillos, ed., Psychology and the Perennial Philosophy (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2013), 148; in-text references elided.

[[11]]: Abbreviations: FC = The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation, ed. David G. Hunter et al., 146 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1947–2023), references to volume and page number; D = St. Jerome, Commentaire sur Jonas, trans. Yves-Marie Duval (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1985)

[[12]]: Dictionnaire encyclopédique de la théologie catholique, vol. 13 (Paris, 1870), 392.

[[13]]: René Guénon, Autorité spirituelle et pourvoir temporelle (Paris: Guy Trédaniel/Véga, 1984), 102.

[[14]]: Joaquín Albaicin, interview with Rama P. Coomaraswamy, Letra y spiritu 17 (May 2003). In Spanish; the English translation has since vanished from the Internet.

[[15]]: In the generally godless modern age, literature is the keeper of (profane) wisdom. Mastering its artifices is mastering the key to the age. The puzzling and labyrinthine ways of modern literature places the reader in the initiatic figure of the hero on the quest for understanding. Speaking about Finnegans Wake, Northrop Frye wrote: “Eventually it dawns on us that it is the reader who achieves the quest, the reader who, to the extent that he masters the book of Doublends Jined, is able to look down on its rotation, and see its form as something more than rotation.” Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 323–24. Eliade made similar observations on modern literature as modern initiation trial.

[[16]]: Guénon, Autorité spirituelle et pourvoir temporelle, 102.

[[17]]: Mircea Eliade, Le sacré et le profane (Paris: Gallimard, 1965), 16; emphasis given.

[[18]]: Marco Pallis, “Do Clothes Make the Man?” in Martin Lings and Clinton Minnaar, eds., The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2007), 267.