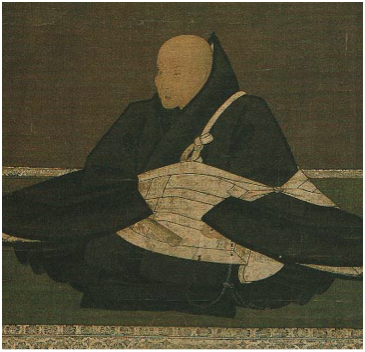

Buddhism is often considered among the most peaceful of religions. Indeed, those with a slender grasp of this tradition may think of it as little more than practising simple meditation with a view to attaining some measure of serenity, however that might be envisaged. But what is the deeper meaning of peace, and how can we appreciate its significance in light of fundamental Buddhist principles? An attempt will be made to answer this question from a pastoral perspective. In particular, I shall explore the unique doctrinal features of Shin Buddhism that can help us confront one of the greatest challenges we face: namely, how can an ordinary, unenlightened being ever hope to attain any kind of enduring tranquility in a world that is uncertain, and where nothing stays the same? Our prospects do not appear to be very promising when we hear these sobering words from the founder of this school, Shinran Shonin (1173–1263):

"Our desires are countless, and wrath, jealousy and envy are overwhelming, arising without pause; to the very last moment of life they do not cease, or disappear, or exhaust themselves."[[1]]

Or when the Avataṃsaka Sūtra delivers this rather unwelcome reminder:

"The terror of the calamities in our woeful states of misery are harsh and violent, continuous and manifold."[[2]]

So where do we go to from here? Given the unreliable conditions of our existence, what can we do about it? Short of becoming supremely awakened, our situation must appear rather hopeless. After all, Shin Buddhism teaches that we cannot become buddhas in this life; neither does it prescribe contemplative practices or good works to subdue our binding impulses. Furthermore, it avoids any kind of perfectionist spiritual idealism that is unattainable by “foolish beings”, as we are described by Hōnen (1133–1212). While this realistic assessment is actually rather commendable and refreshing to hear, it might make us feel lost at sea, as we dejectedly wonder whether there is any way out of our plight.

To be perfectly candid, it ought to be apparent that we all have an emotional dependence on the world for our happiness and security. We readily observe ourselves and others chasing after experiences we think will fulfill us; for example, health, beauty, pleasure, love, comfort, power, status and wealth. Being happy is then seen as getting—and hanging on to—desirable things.

Many people feel compelled to project a face to the world that makes them appear confident, purposeful and empowered, whereas behind this façade we tend to conceal our real self—which is often fearful, unsettled and vulnerable. Why is this so? The Buddha taught that life resembles a ceaselessly turning wheel that never allows anything to remain stable. We see evidence of this truth all around us on a daily basis. But here is the problem: If our sole objective is getting what we want, how do we cope when our endeavours fail? Even if we achieve some degree of success, after much struggle, what do we do when this wheel turns again, and the cherished objects that we covet so dearly begin to slip away, or are suddenly wrenched from us?

There is no freedom in being captive to circumstances that are always changing, because phenomena beyond our control are being allowed to dictate whether we are peaceful or troubled.

As we can see, this agitated toil to secure gratifying experiences and sensations leads to a “yo-yo” life. Striving in this way, we get tossed around between great highs and terrible lows, because the iron law of impermanence cannot be defied. So we go from being jubilant to sad, then cheerful again, before being knocked down once more into the same old dissatisfaction, which we have not managed to shake off. This is a losing game because we are banking on events that are never dependable.

When relying on the world or other people to safeguard our happiness, we are looking in the wrong place. There is no freedom in being captive to circumstances that are always changing, because phenomena beyond our control are being allowed to dictate whether we are peaceful or troubled. Neither can there be any real equanimity when we keep fearing the loss of everything we treasure, for this is impossible on such hazardous terms.

This dependence on external things is what fuels the anxiety, disquiet, and resentment that so often seethe beneath the surface of our lives. We frantically clutch at what we simply cannot hold on to, and so we suffer. Besides, our very bodies are a source of constant distress to us, because we know that their unavoidable destiny is old age, sickness and death. Yet, even when things happen to look sunny and carefree, it is quickly forgotten that our mortality is an inescapable certainty, because we will want to suppress the underlying dread that this is the end of life altogether (at least as we imagine it to be).

So, is an unchanging happiness possible? Might it be foolish to yearn for a well-being that is always available to us? But how can this be when we are told that there is no lasting delight in this transient life, or in satisfying our relentless cravings with minds infested by “snakes and scorpions”, as Shinran would say?[[3]]

Śākyamuni disclosed a fact of immense spiritual importance. He declared that the entire universe (including every aspect of our experience) is thoroughly pervaded by a dynamic and omnipresent Wisdom–Compassion that is known in the Pure Land tradition as Amida, the Buddha of Immeasurable Light and Life. This is the accessible face of ultimate reality, which would otherwise remain entirely inconceivable to us. Its sole purpose is to grasp those who are lost in pain and anguish, immersing them in another world, while they remain fully rooted in this one. Indeed, this experience imparts a clarity and composure that is able to withstand many earthly trials, thus vividly confirming the truth of Dharma, and making tangible the impact of “Other-Power” in our turbulent lives.

Awakening to this presence is not just having a religious belief or defending some dogma; rather, it is to receive the wisdom conferred by Amida, which is the only method available to the average person. By seeking a haven in this limitless reality, it comes alive in us as a new mind of awareness, and a new heart that is undisturbed. This, to be sure, is the antidote for our dogged clinging to things that fade and perish. We are therefore brought to rely on that which is “true and real” (shinjitsu) instead of the false existence we take as genuine but which is, in fact, insecure, aimless and full of affliction.

When cut off from real life, it sometimes feels as though we are running out of oxygen, gasping for air as we suffocate in our own despondency. This crisis is manifested, moment-by-moment, in ordinary people “whose greed is profound, whose anger is fierce and whose ignorance smoulders” as observed by Kakunyo (1270–1351).[[4]] Yet, the illuminating action of Amida makes us see this wretched state as our undeniable inward condition, which is then expressed outwardly as thoughts and feelings that have gone adrift in a fog of bewilderment. So, even though the ultimate origin of suffering “is not discernible”, according to the Mātu Sutta[[5]], the light of wisdom at least points to the more immediate cause of travail within ourselves, thus thwarting the need to condemn others or blame the world for all our problems.

There is enormous relief when this happens, even in the midst of difficult or vexing conditions. So long as we remain common human beings, we cannot avoid disagreeable experiences, though we are able to receive a peace that remains settled in the face of conflict. True wisdom thus illumines our situation to make us see things as they really are. In that way, the heavy impact on us of the world is alleviated, because we are no longer invested in it as the abiding source of our welfare. We continue, of course, to function regularly in life, discharging our roles and responsibilities as required, but we are no longer held captive by the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”.[[6]]

…the solution to our perilous human condition is not to be found on the same level as the problem itself…

This Wisdom–Compassion, which reaches out as an ever-calling voice (nembutsu), reminds us that we are enveloped at all times, though we may not always be aware of it. Whenever perturbed, we can always turn to this actively benevolent force, which soothes our parched spirits and dispels confusion. Its influence serves to soften our stony hearts, and diminishes the tenacious attachment to things that invariably give rise to disappointment.

Such momentous transformation is only possible by means of an intervention that cannot arise from our darkened minds or misdirected loves. Which is to say that the solution to our perilous human condition is not to be found on the same level as the problem itself; because, in the end, true peace can neither be bestowed nor shaken by what the world does, or by what others say or do.

People have a desperate need to resolve their unhappiness and sense of deficiency, but because they fear coming to terms with what they are really like, there is strong resistance to admitting that their mundane hopes have failed them (either because of misguided expectations or a denial of their own misery). Instead, the Dharma urges us to relinquish the pretence of being happy in a fleeting world that has not delivered the enduring fulfillment we were promised. We can then approach Amida’s light of compassion (jikō)—with confidence and humility—precisely as flawed and damaged human beings.

This realization opens the door to real entrusting; to a letting go of the self-willed struggle to fix our brokenness, which will never work because it means always having to maintain a fruitless battle against ourselves. Rather, we are urged to take shelter in the Primal Vow[[7]] which seeks to regenerate our lives, in whatever state we find ourselves, and to bring us to our permanent abode at the time of death, when we enter the gate of final deliverance “without severing blind passions” as taught in Shin Buddhism.[[8]] This is to become inseparably united—in unending exaltation—to the timeless state of Nirvāṇa, which the Larger Sutra on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life describes as “pure, serene, and resplendent”[[9]], and of which Shandao (613–681) observes that being “undefiled and unarisen, it is true reality”[[10]]. We recall, as well, Shinran’s renowned depiction of it as follows:

"Nirvāṇa is … uncreated, peaceful happiness, eternal bliss, and true reality, . . . it fills the hearts and minds of the ocean of all beings."[[11]]

In its aspect as consummate quietude, we are taught that it is also known as annyō which, while undoubtedly denoting a transcendent sphere, conveys the additional sense of us being sustained and nurtured at all times, until our unfavourable karma is eventually exhausted. Again, in the Larger Sutra, we read:

"If sentient beings encounter the Buddha’s light, their defilements are removed; they feel tenderness, joy and pleasure, and good thoughts arise. If sentient beings in the realm of suffering see this light, they will be relieved and freed from affliction. At the end of their lives, they all reach emancipation."[[12]]

Hence, we come to see that annyō represents both a destination and a living reality that permeates everyday life. The Tannishō declares that:

"Even when we are afflicted by blind passions, if we revere the power of the Vow all the more deeply, gentle-heartedness and forbearance will surely arise in us through its spontaneous working."[[13]]

This is what allows us to live a spiritually amphibious existence, straddling both seen and unseen worlds at the same time. In one of his hymns, Shinran asserts that “Although my defiled life is filled with all kinds of desire and confusion, my mind is playing in the Pure Land”.[[14]] And herein lies a great mystery. The Buddha’s Fire Sermon proclaims that we are floundering in a world “burning with the fire of passion, the fire of hatred, the fire of delusion … burning with the fire of birth, decay, death, lamentation, pain, and despair”.[[15]] Nevertheless, though we may be plunged into turmoil with wounded hearts, sanctuary may still be found in the “serene sustenance” of annyō. Yet, some will raise the following objection: Isn’t all this talk of an other-worldly mystical euphoria just a symbolic projection of the better conditions that we ought to create here and now—in this life—through worthy initiatives dedicated to overcoming oppression, conflict, prejudice and hatred?

That is not the orthodox understanding of the Pure Land. One cannot take comfort in a cold, bloodless symbol that refers to nothing but the amelioration of the planet’s endemic disorders; rather, the traditional masters insist that this realm represents a ubiquitous spiritual reality; which is not to deny that Shinran wished (as we all should) to see peace prevail in the world by spreading the Buddha’s teaching.[[16]] However, he most assuredly did not believe that this “burning house”, which is our earthly domicile, could ever be transfigured into an ever-lasting arena of bliss, given the sorry state of our ruptured humanity which the Larger Sutra strikingly portrays as follows:

"Groaning in dejection and sorrow, they pile up thoughts of anguish or, driven by inner urges, they run wildly in all directions and thus have no time for peace and rest ... Gnawing grief afflicts them and incessantly troubles their hearts. Anger seizes their minds, keeps them in constant agitation, increasingly tightens its grip, hardens their hearts and never leaves them … they drink bitterness and eat hardship … Because they are deeply troubled and confused, people indulge their passions. Everyone is restlessly busy, having nothing on which to rely. Thus, they entertain venomous thoughts, creating a widespread and dismal atmosphere of malevolence."[[17]]

How can we bring about any kind of utopia when our lives are so hopelessly steeped in the poisons of avarice, ill-will and folly? Have we ever seen a bright day since the dawn of humanity? This might well be because—as unregenerate beings—we are the problem and have always been so. Admittedly, these unsparing truths are very hard to listen to; they make us intensely uncomfortable, so we rush to gloss over them.

…we are the very hell from which we need saving, and brutally honest introspection alone will reveal our incapacity for self-liberation…

As it stands, the world cannot give us authentic peace, for this is only possible when we are made to rest in Amida’s working with complete self-abandonment. So, if you believe that there is nothing real other than this cycle of birth-and-death, fuelled by endlessly fleeting causes and conditions, then we are left without hope; for both fragility and futility are firmly baked into samsāric existence. Only when we are struck by this confronting realisation, does the prospect of true hope then become apparent for the first time. We must acknowledge our own helplessness in light of this impasse, because there is no joy in ego satisfaction, or in repressing the fact that we all suffer from the very spiritual illness diagnosed by the Buddha. Otherwise, the only effective remedy continues to remain out of reach, and we will persist in thinking that we are perfectly good, kind, peaceful and loving people when, in reality, our hearts conceal an abyss of hidden rage and discontent. In other words, we are the very hell from which we need saving, and brutally honest introspection alone will reveal our incapacity for self-liberation. Only Amida’s Vow can release us from the burden of being ourselves, and from the tribulations of an ephemeral world.

Yet some continue to doubt that there is a realm which transcends this painfully mutable cosmos. They appear to harbour the inexplicable misapprehension that the much-invoked mantra of “saṃsāra is Nirvāṇa” means that these terms are somehow identical (in any case, only the wisdom of a Buddha could ever know that). It would make more sense to view them as equally indescribable, unimaginable and ineffable, which is why they are both “empty” according to Mahāyāna thought. While intimately interfused, they are certainly not equivalent, as though Nirvāṇa can simply be reduced to saṃsāra at the level of our experience—that would be absurd.[[18]] Do secular-minded Buddhists, who actually think this way, believe that an improved form of life, as birth-and-death, is really the goal of our existence? If so, then I invite them to take refuge in that and to let the rest of us know how this works out. It was well said, by the great Mādhyamaka scholar Gadjin Nagao, that “Emptiness is not a mere nihilism that engulfs all entities in its universal darkness … On the contrary, [it] is the fountainhead from which the Buddha’s compassionate activity flows out.”[[19]]

This is the fatal contradiction of relativism: it must logically end up doubting its own scepticism as well.

If we insist that even Nirvāṇa is a conditioned reality that is subject to dependent origination, along with everything else, then there is no unassailable standpoint from which that fact can be established as true in the first place (because then the very notion of absolute truth itself, paramārtha–satya, is totally undermined). This is the fatal contradiction of relativism: it must logically end up doubting its own scepticism as well. If our spiritual longing is not based on what is incorruptible—or “diamond-like” as the faith-mind or shinjin is described—then all we have left (apart from an effect without a cause) are just impotent efforts at consolation based on mere subjective wishful thinking. No psycho-babble or political ideology can help us to appreciate Shinran’s vision. In fact, his incisive teaching serves to reveal the poignant limitations of any worldly solution to this problem.

In Chapter 18 of the Mūlamadhyamakakārika, Nāgārjuna himself—when reflecting on the nature of true reality (tattva)—states that it is “indeterminate”, “not caused by something else”, “not elaborated by discursive thought”, and “without differentiation”; more importantly, we are told that it is also “peace”. As we can see, he explicitly equates tattva (which is, after all, a synonym for Nirvāṇa, Suchness or the Dharma-Body) with an unconditioned reality that is not subject to pratītyasamutpāda for its existence. So, even though we are penetrated by that which is non-dual, our limited capacity as ordinary beings (pṛthagjana) means that we can conceive of this fact only in a dualistic manner. In Chapter 25, Nāgārjuna observes:

"That which comes and goes

Is dependent and changing.

That, when it is not dependent and changing,

Is taught to be Nirvāṇa."[[20]]

Furthermore, he points out that this reality is “uncompounded” which recalls the following text from the Pāli canon:

"There is, monks, an unborn, unoriginated, uncreated, unconditioned. If, monks, there were not that which is unborn, unoriginated, uncreated, unconditioned, there would be no escape from what is born, originated, created, and conditioned."[[21]]

In his commentary on Nāgārjuna’s magnum opus, Jay Garfield notes that: “Nirvāṇa is negatively characterized as release from saṃsāra and the constant flux, aging, death, and rebirth it comprises. But this means that, since all entities have these characteristics, Nirvāṇa cannot be thought of as an existent entity. And here we must be very careful … for neither do we want to say that Nirvāṇa is non-existent.”[[22]] Quite so, because that would render the Dharma both unintelligible and ineffectual.

Also illuminating is Nāgārjuna’s Acintyastava (“Hymn to the Inconceivable”). In verses 44–45, he tells us that, whereas the conventional arises from causes and conditions—and is thus relative—the ultimate reality is not produced by anything; this is because it has the attributes of own-being (svabhāva), substance (dravya), the real (vastu), and the true (sat).[[23]] Clearly, then, the use of such terms is perfectly acceptable when applied to that which is, in every sense, absolute. To deny this is to succumb to the grave error of annihilationism, or kūken; in contrast to jōken, which is the corresponding fallacy of attributing permanence and a substantial essence to the volatile dharmas of our contingent world, all of which lack self-sufficient being.

Thus, we can see that the Pure Land alone—as annyō—affords true peace, precisely because of its unceasing felicity; it remains deathless, beyond the clutches of a precarious transience that can never satisfy us (and whose end cannot be found in itself). And because, in truth, we are ordered towards the imperishable—and to the utmost joy that is innate to it—this also represents the highest good there is. So, given our boundless buddha–nature (not our unfixed, insubstantial personalities), we are assured that our deepest aspiration will indeed be fulfilled because, in the words of Shinran’s great-great grandson, Zonkaku (1290–1373):

"Generating a place where there is no falsity … or transmigration, the Buddha aspires to benefit sentient beings by giving them a great realm of ultimate purity, peace and sustenance."[[24]]

John Paraskevopoulos was ordained as a Shin Buddhist minister in 1994 in Kyōto, Japan, and holds a first-class honours degree in Philosophy from the University of Melbourne in Australia. His publications—which have been translated into French, Italian, Portuguese and Greek—include Call of the Infinite, The Fragrance of Light, The Unhindered Path, andImmeasurable Life.

__________________________

[[1]]: The Collected Works of Shinran: Volume I (Kyoto: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha 1997), p. 488

[[2]]: The Flower Ornament Scripture, tr. Thomas Cleary (Boston: Shambhala, 1993), p. 1337

[[3]]: The Collected Works of Shinran, p. 422

[[4]]: Alfred Bloom (ed.), The Shin Buddhist Classical Tradition: A Reader in Pure Land Teaching [Volume 2] (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2014) p. 109

[[5]]: Saṁyutta Nikāya, 15:14–19

[[6]]: William Shakespeare, Hamlet (Act III, Scene 1)

[[7]]: The fundamental will of ultimate reality to liberate all beings from the torrid cycle of saṃsāra

[[8]]: The Collected Works of Shinran, p. 70

[[9]]: The Three Pure Land Sutras, tr. Hisao Inagaki (Kyoto: Nagata Bunshodo, 2000), p. 263

[[10]]: Quoted in The Collected Works of Shinran, p. 201

[[11]]: The Collected Works of Shinran, p. 461

[[12]]: The Three Pure Land Sutras, p. 255

[[13]]: The Collected Works of Shinran, p. 676 [adapted]

[[14]]: Jōgai Wasan No.8

[[15]]: Saṃyutta Nikāya, IV.19

[[16]]: The Collected Works of Shinran, p. 560

[[17]]: The Three Pure Land Sutras, pp. 282–286 (passim), and p. 304

[[18]]: A more nuanced insight can be found in the Vimalaprabhā, an 11th-century commentary on the Kālacakra Tantra attributed to Kalkī Śrī Puṇḍarīka, the mythical second king of Shambhala (and purported manifestation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara). In this text, we find the following: “Like shadow and sun, [samsāric] existence and nirvāna are not identical.” (John Newman, The Outer Wheel of Time: Vajrayāna Buddhist Cosmology in the Kālacakra Tantra, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1987, p. 373). In other words, although a shadow is not directly created by the sun, neither can it arise without the presence of the latter; therefore, while certainly inseparable, they are not the same thing. Thus, the relationship between them remains a mystery

[[19]]: Gadjin M. Nagao, Mādhyamika and Yogācāra: A Study of Mahāyāna Philosophies (Albany: SUNY Press, 1991), p.206

[[20]]: The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, tr. Jay L. Garfield (Oxford University Press, 1995), p.74

[[21]]: Udāna VIII.3

[[22]]: Garfield, pp. 324-325

[[23]]: Christian Lindtner, Master of Wisdom: Writings of the Buddhist Master Nāgārjuna (Berkeley: Dharma Publishing, 1997), p.24

[[24]]: Bloom, p. 119