One of the great difficulties in the appreciation of the religious consciousness is the idea of ’religion‘ itself. The term ’religion’ has developed connotations that have little or nothing to do with more traditional understandings of this word, a point, of course, that begs the question of the autonomy of words. It is said by some that the word ’religion‘ means what it does for us precisely because that is how we understand it. In contrast, all traditional societies appreciate that words precede their understanding. 'In the beginning was the Word,' says St. John. From this point of view the shifting connotations associated with the idea ’religion‘ represent not an evolution but a devolution, a movement away from the original accompanied by a subsequent distortion of meaning. It is a sign of mental weakness and laziness to accept a distortion as the norm simply because it corresponds to one's own time.[[1]]

[[1]]: Martin Lings feels that modern man is unique in having fallen so far as to lose sight of the norm, to the point of questioning its existence, and even of fabricating a new ’norm‘ out of the limitations of his own decadent experience (Lings, The Eleventh Hour, 1987, p.16-1).

The word ’religion’ suggests a complex interplay of social, spiritual, psychological, ritual, mythological, and political elements. The blanket grouping of these various areas is partly where the problem begins. Eric Sharpe observes that it is all too easily forgotten by Western students that many languages simply do not have an equivalent of the word ’religion’ in their vocabulary. ’”Law,” ”duty,” ”custom,” ”worship,” “spiritual discipline“, ”the way”, they know: ”religion” they do not.’[[2]] For Sharpe the trouble lies with the strong political and moral overtones that the Latin word religio has.

Whitall Perry recalls a conversation with a Native American Iroquois Indian who, when asked about ’religion‘, responded:

’Religion - it's a crutch for people who need it. A crutch is better than nothing, but people who can walk on their two feet spiritually don't need a crutch. If you see the Great Spirit in everything, if it acts in everything you do, then you don't need this crutch!’ [[3]]

[[2]]: Sharpe, Understanding Religion, 1975, p.39.

[[3]]: Perry, The Widening Breach, 1995, p.37.

Religion is again the formal transmitter of Tradition, that is to say, it is a continuous ’re-reading‘ of Tradition.

The idea of religion, as it has come to be portrayed in the modern West, is often seen to suggest an impression of spiritual deficiency. While this may be true in practice, this view does nothing but damage a beneficial understanding of religion.

Sharpe observes the attempts of Cicero and Lactantius to derive the basis for the word ’religion‘ as being respectively from the verbs relegere (to re-read) and religare (to bind fast).[[4]] However, he remarks that there is no way of knowing which is right. Titus Burckhardt observes that the Latin term religio has as one of its meanings that of ’debt.‘ [[5]] Sharpe's appreciation of religion suffers from looking for a particular meaning of the word. Burckhardt recognizes that ’debt‘ is but one of the meanings of this word. Religion is in fact multivalent. This does not however mean that arbitrary connotations can be legitimately assigned to the word ’religion’ according to the confusions or individual fantasies of the times. The valences of religion are integral, concordant and necessary. Religion, like the Taoist ’Way‘ embodies all the elements of ’law,’ ‘duty,’ ‘custom,’ ‘worship,‘ and ’spiritual discipline.‘ Furthermore, the word religio carries within it each of the above senses in that it expresses the relationship between the human and the Divine. Religion is that which ’binds‘ the human to the Divine. This is the Logos or the Intellect, as Meister Eckhart understood this term. In fact the Arabic word for the Intellect, al-'aql, is related to the word ’to bind.’ [[6]]

Religion is again the formal transmitter of Tradition, that is to say, it is a continuous ’re-reading‘ of Tradition. The term ’Tradition,‘ from the Latin tradare (‘to give over’), here designates a transmission from one generation to another of doctrines concerning a direct, intuitive knowledge, free from accidents and limitations of particularities; it is an unbroken chain to a revealed source.[[7]] At a deeper level, this is analogous to the unbroken ’Chain of Being’ which acts in successional mode within the timeless simultaneity of Eternity.[[8]] Hence, religio is both the literal ’re-reading’ of the sacred Scriptures and the eternal ’re-reading‘ of the cosmogonical Word, as taught by Meister Eckhart and later by Angelus Silesius.

[[4]]: Sharpe, Understanding Religion, 1975, p.39.

[[5]]: Burckhardt, An Introduction to Sufi Doctrine, 1976, p48, n.1.

[[6]]: See Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred, 1981, p.12. Susan Davies observes that this might well be compared with the Scholastic principle of Synteresis, which literally means, 'a binding'." (Uncreated Light, 1997, p.8. n.11)

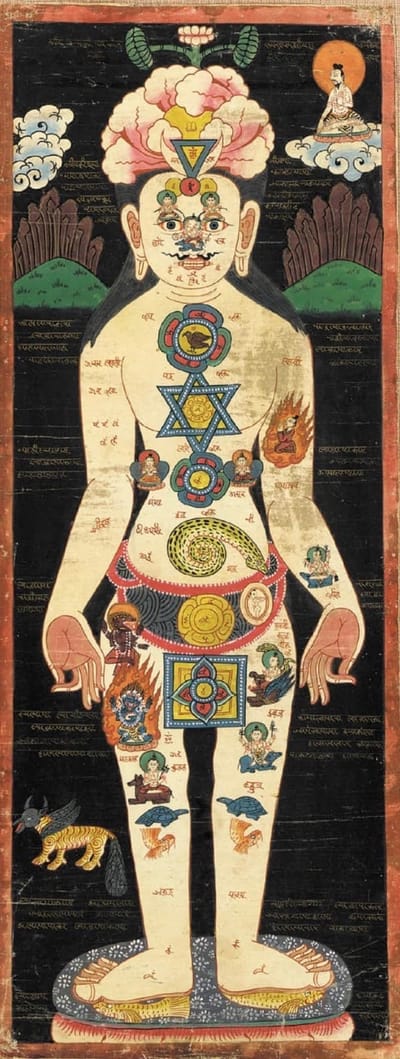

The notion of religion as ’debt‘ supports the idea of that which ’binds.‘ Debt binds the two parties that it involves. Humans recognize their ’debt‘ to God, as the Principle of their existence. In a more contingent sense it can be said that God, at least at the level of Immanence, is ’indebted’ to man insomuch as man must exist to satisfy the Divine All-Possibility. The term ’man’ is used here deliberately even though it has undeniably suffered the same confusions and perversions as the word ’religion.‘ Seyyed Hossein Nasr stresses that in English ’man‘ signifies at once the male and the human being as such, like the Greek anthropos, the German mensch or the Arabic insan. Man refers not only to the male but to the human state whose archetypal reality is the androgyne reflected in both the male and female. [[9]] Moreover, individual man is but a particularized reflection in the synthesis of ’Universal Man,’ which is none other than Being Itself. The term ’Universal Man‘ (al-insan al-kamil) is here borrowed from the teachings of Muhyiddin ibn 'Arabi and 'Abd al-Karim al-Jili. This idea of Man as Being or Universal Existence is also found with the Adam Kadmon of Kabbalah, and the ’King’ ( Wang) of Taoist tradition. [[10]] Inasmuch as Man is ’necessary Being‘, God is ’indebted’ to man, for the Absolute must by definition include the Relative.[[11]]

[[7]]: Snodgrass, Architecture, Time and Eternity, Vol. I, 1990, p.l, n.l.

[[8]]: As examples of this see Plato, Timaeus 29A-13, 371), 3-5, Plotinus, Enneads 3.7, and others cited in Snodgrass, Architecture, Time and Eternity Vol. I , 1990, Ch.B; sec also Guénon, Fundamental Symbols, 1995, ch.63 'The Chain of the Worlds.'

[[9]]: Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred, 1981, p.183, n.1. Nasr concludes, "there is no need to torture the natural structure of the English language to satisfy current movements which consider the use of the term ’man’ as a sexist bias, forgetting the second meaning of the term as ‘anthropos.'

The religio perennis has as its complement and entelechy eschatology which, at its deepest level, is the return of man to God, the realization of ’Supreme Union.’

Religion in its deepest sense is the religio perennis, the essential and principial relationship between God and man. Religion is the two-way

language of communication between man and God where the term ’language’ refers to revelation, ritual, prayer and mantra, as well as the Eternal communication of the cosmogonic Word. The essential core of the religio perennis is the sophia perennis, or universal gnosis, which is essentially concerned with metaphysics. The sophia perennis has as its application and complement the cosmologia perennis, the science of cosmology.[[12]] The religio perennis has as its complement and entelechy eschatology which, at its deepest level, is the return of man to God, the realization of ’Supreme Union.’ Moreover, as ibn 'Arabi teaches, it is not a question of ’becoming one‘ with God, rather the contemplative becomes conscious that he ’is one’ with Him; he ’realizes’ real unity.[[13]]

A distinction can be drawn between the religio perennis and religion as it appears in respect to its limitation to the ’extensions of the human individuality‘.[[14]] This distinction, as René Guénon remarks, is required to forestall the Western misunderstanding that tends to confuse the relationship between metaphysic and religion; to appreciate this relationship correctly is to understand that ’between the two viewpoints there is all the difference that exists in Islam between the haqiqah (metaphysical and esoteric) and the shariyah (social and exoteric).‘[[15]] Frithjof Schuon observes that 'A religion is a form, and so also a limit, which contains the Limitless, to speak in paradox.‘[[16]] Religion in essence is the substance of form; the relationship between God and man is Manifestation itself. And, as Schuon says, 'To say manifestation is to say limitation.'[[17]]

[[10]]: See Burckhardt (tr.), 'Abd al-Karim al-Jili, al-insan al-kamil (Universal Man), 1983; Guénon, Symbolism of the Cross, 1975, ch. II. In his introduction, Burckhardt says, 'the cosmos is, then, like a single being;- ‘We have recounted all things in an evident prototype‘ (Koran XXXVI). If one calls him ‘Universal Man,‘ it is not by reason of an anthropomorphic conception of the universe, but because man represents, on earth, its most perfect image.' (p.iv).

[[11]]: 'The All-Possibility must by definition and on pain of contradiction include its own impossibility.' - Schuon, Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, 1987, p.108.

[[12]]: Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred, 1981, p.190.

[[13]]: This comes from Schuon, Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, 1987, p. 108. This realization is that of the Divine Uniqueness (al-Wahidiyah).’

[[14]]: As observed by René Guénon, Man and his Becoming, 1981, p.156.

[[15]]: Guénon, Symbolism of the Cross, 1975, p.102, n.4.

[[16]]: Schuon, Understanding Islam, 1976, p.144.

[[17]]: Schuon, In the Face of the Absolute, 1989, p.35.

This agrees with the reading of ’religion’ as ’that which binds,‘ for this is the same as ’that which bounds,’ being the boundary of indefinite Manifestation within the Divine Infinitude. Hence, religion at all its levels reflects its essential nature as ’form‘ and ’limitation.’ Thus with respect to religions as ’extensions of the human individuality‘, Schuon remarks, 'every form is fragmentary because of the necessary formal exclusion of other possibilities; the fact that these forms ... each in their own way represent totality does not prevent them from being fragmentary in respect of their particularization and reciprocal exclusion.’[[18]] Again, Nasr says, 'Each revealed religion is the religion and a religion, the religion inasmuch as it contains within itself the Truth and the means of attaining the Truth, a religion since it emphasizes a particular aspect of Truth in conformity with the spiritual and psychological needs of the humanity for whom it is destined.’ [[19]] Schuon remarks that a religion is 'not limited by what it includes but by what it excludes.’[[20]] This has its root in the fact that Manifestation limits itself by exclusion of the Infinite. Still, as Schuon continues, ’since every religion is intrinsically a totality, this exclusion cannot impair the religion's deepest contents.’[[21]] A religion, strictly speaking, must satisfy all spiritual possibilities. Hence, says Schuon, Shintoism, for example, is not a total ‘religion’ but requires a superior complement which Buddhism has provided.[[22]]

The sophia perennis lies at the heart of each and every orthodox religion. ’Orthodoxy’ provides the starting point in the study, practice and understanding of religion. However, this term should not be taken as simply indicating the restricted ’orthodoxy’ of the Western religious conception. The 'necessary and sufficient condition' of orthodoxy, as Guénon remarks, is the 'concordance of a conception with the fundamental principle of the tradition.’[[23]] These ’principles‘ are none other than the sophia perennis. An orthodox religion is expressed through myth, ritual and doctrine, each infused and underpinned with symbolism.

[[18]]: Schuon, Understanding Islam, 1976, p.144.

[[19]]: Nasr, Ideals and Realities of Islam, 1966, p.15.

[[20]]: Schuon, In the Face of the Absolute, 1989, p.79.

[[21]]: Schuon, In the Face of the Absolute, 1989, p.79.

[[22]]: Schuon, Language of the Self, 1999, p.154.

[[23]]: Guénon, Man and his Becoming, 1981, p.15.

At the ’historical’ level the religious consciousness develops according to a sequential schema that in turn accords with the succession mode of Being. Gershom Scholem sets out such a schema in his work, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism.[[24]] To summarize: The first stage of religious consciousness is one in which no ’abyss‘ exists between ’Man and God.’ Scholem calls this the ’mythical epoch’: it is the Golden Age, the Edenic state. This is the ’immediate consciousness‘ of the ’essential unity,‘ where this unity ’precedes duality and in fact knows nothing of it.’ Metaphysically speaking this is religion in divinis or in potentia insomuch as it corresponds at the analogous level with Formless Manifestation. Thus says Meister Eckhart, ’before the foundation of the world (Jn.17:24) everything in the universe was not mere nothing, but was in possession of virtual existence.’[[25]] In this first stage, says Scholem, ’Nature’ is the scene of man's relation to God. Metaphysically this rejects the non-distinction of man and God within ’primordial Nature,’ where Nature is understood in the same sense as the Hindu term ’prakriti.’ Prakriti is said to mean ’that which is transcendent’: 'The prefix pra means ’higher’; krti (action) stands for creation. Hence she who in creation is transcendent is the transcendent goddess known under the name of Nature (prakrti).’[[26]]

[[24]]: Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 1995, p.7-8.

[[25]]: Eckhart, Comm.Jn. n..15, sec also Par. Gen. n.55.

[[26]]: Brahma-vaivarta Purana 2.1.5.[43] cited in Danielou, The Gods of India, 1985, p.31.

[[27]]: Guénon, Man and his Becoming, 1981 , p.164. In this context Whitall Perry notes the Vedantic doctrine of bhedabheda or 'Distinction without Difference.' (The Widening Breach, 1995, p.15).

The second stage is the ’creative epoch‘ in which the emergence of formal religion per se occurs. Scholem remarks that ’Religion's supreme function is to destroy the dream-harmony of Man, Universe and God.‘ In this ’classical form’ ’religion signifies the creation of a vast abyss, conceived as absolute, between God, the infinite and transcendental Being, and man, the finite creature.‘ This ’abyss’ can be crossed by nothing but ’the voice’: the voice of God, directing and law-giving in His revelation, and the voice of man in prayer. Scholem observes that the great monotheistic religions live and unfold in the ever-present consciousness of this bipolarity. This reflects the cosmogonic Voice which, as the principle of Universal Being, implies the bipolarity of ontological Essence and Substance. ’It is true‘, says Guenon, ’that Being is beyond all distinction, since the first distinction is that of ’essence’ and ’substance‘ or of Purusha and Prakriti; nevertheless Brahma, as Ishvara or Universal Being, is described as savishesha, that is to say as ’implying distinction,‘ since He is the immediate determining principle of distinction.’[[27]] For the humankind of this period the scene of religion is no longer Nature, but the moral and religious action of man and the community of men, whose interplay brings about history as, in a sense, the stage on which the drama of man's relation to God unfolds.[[28]]

It is in a sense in reaction to the solidification of this ’classical‘ expression of religion that the phenomenon called ’mysticism‘ arises. Scholem likens mysticism to the ’romantic period of religion.’ ’Mysticism‘ he remarks, ’does not deny or overlook the abyss; on the contrary, it begins by realizing its existence, but from there it proceeds to a quest for the secret that will close it in, the hidden path that will span it. It strives to piece together the fragments broken by the religious cataclysm, to bring back the old unity, which religion has destroyed, but on a plane where the world of mythology and that of revelation meet in the soul of man.'[[29]]

At its metaphysical level ’Mystery’ refers to the necessary enigma of the relationship between Immanence and Transcendence or between the Relative and the Absolute…

The term ’mysticism,’ as Burckhardt observes, has, like the words ’religion‘ and ’man,’ suffered at the hands of religious individualism and modern confusion, losing its precision.[[30]] ’Mysticism’ derives from the root meaning of ’silence,’ as in a knowledge inexpressible because escaping the limits of form.[[31]] Properly speaking it refers to the idea of ’mystery.‘ This is the mystery of the Silence that precedes the speaking of the cosmogonic Word.[[32]] The contemporary Kabbalist, Z'ev ben Shimon Halevi, says that the best that can be said of this is that it is ’perhaps like the pregnant pause before a concert begins, or the moment just like prior to dawn when nothing can be seen or heard, yet everything is present and potential.’[[33]] At the human level this is expressed in the initiatory ’Mysteries,’ the Greater and Lesser Mysteries. At its metaphysical level ’Mystery’ refers to the necessary enigma of the relationship between Immanence and Transcendence or between the Relative and the Absolute; the mystery of the Hypostatic Substance; again, the mystery of the Universal Spirit, the Intellect, of which Meister Eckhart says that it is uncreated and not capable of creation, yet is the principle of creation. This enigma is an imperative of Universal Existence. Impenetrable to the discursive mind, it can only be approached by the likes of the Zen koan or the apophatic theology of a Pseudo-Dionysius.

Man and God are bound by the ’blood debt’ instigated when God sacrificed (so to speak) His Infinitude to the limitation of Being.

This schema reflects the successional mode of Existence, but it is also true that there is a simultaneous mode of Existence, so that each of these stages may be found within any given religion at any given time. Thus, in its simplest formulation, religion can be said to comprise two fundamental aspects or levels: ’exoteric’ and ’esoteric.’ A doctrine is exoteric, observes Schuon, to the degree that il is ’obliged to take account of individualism’; esoterism, on the other hand, views the Universe ’not from the human standpoint but from the ”standpoint“ of God.’[[34]] Again, Schuon remarks that ’inwardly‘ every religion is ‘the doctrine of the one self and its earthly manifestation, as also the path leading to the abolition of the false self, or the path of our mysterious reintegration of our ’personality‘ into the celestial Prototype; ’outwardly‘, the religions are mythologies or, to be more exact, symbolisms designed for differing human receptacles and displaying, by their limitations, not a contradiction in divinis but on the contrary a mercy.’[[35]]

[[28]]: Scholem, Major Trends In Jewish Mysticism, 1995, p.8.

[[29]]: Scholem, Major Trends In Jewish Mysticism, 1995, p.8.

[[30]]: See note 1, p.i, Burckhardt's introduction to, al-Jili’s al-insan al-kamil (Universal Man), 1983.

[[31]]: Pallis, 'Is There a Problem of Evil?' from Needleman (ed), The Sword of Gnosis, 1974, p.236

[[32]]: ‘Precedes’ in a logical rather than chronological sense, for, of course, this is ’bcfore’ the distinction of time.

[[33]]: Halevi, Adam and the Kabbalistic Tree, 1991, p.21 -22

Man and God are bound by the ’blood debt’ instigated when God sacrificed (so to speak) His Infinitude to the limitation of Being. This limitation is brought about precisely and paradoxically in view of the Divine All-Possibility, which, in the language of Kabbalah is the Divine Mercy and, again, in Muslim terms is ar-Rahmah. This blood debt is answered when a ’Christ‘, as the Way, is sacrificed upon the Cross.[[36]] Christ's answer is literally an ‘answering’ in the sense of a reply, for just as God has spoken the cosmogonic Word in which Existence is ’read,’ so now Christ ’re-reads‘ himself, the Word made flesh, in return to God. In this act of Universal salvation and mercy religion finds its entelechy. This is the saving mercy that in Islam is ar-Rahim. Born of mercy, religion returns through mercy; thus may it be said that religion is properly defined as the ’Way of Mercy.’

[[34]]: Schuon, Language of the Self, 1999, p.20-1.

[[35]]: Schuon, Language of the Self, 1999, p.20-1.

[[36]]: Christ as the Way refers to the Universal Christ principle as much as to Christ localized with Christianity.